Background

This is the fourth in a series of articles (all collated in the category ‘Games that Self-Forecasters can Play’) to help illustrate some of the different self-forecasting approaches that we’re aware of, approaches that were discussed back in 2022 and, in many cases, are still observed in 2025.

In each example we have used real data – but have taken steps to anonymise the data (obscured the DUID and date, and normalized the capacity of the unit) because the purpose of these articles is not to point the finger at any particular unit. The purpose is help readers understand approaches that have been in use.

Readers should keep firmly in mind that:

- As noted before, it’s impossible to know motive – but does not stop us guessing.

- Also, on Sunday 8th June 2025 we see (saw) the commencement of Frequency Performance Payments – which:

- Does both:

- Changes the approach to apportioning Regulation FCAS costs; and

- Establishes a payments and cost recovery mechanism for Primary Frequency Response.

- And in doing so, it also retires the use of the ‘Frequency Indicator’ for apportioning regulation FCAS costs which (in our view) has been exploited for for the behaviours we part of the games note above.

- As a result of this change, we may see changes in these approaches.

- Does both:

Today’s example: Avoiding SDC periods

In the case when a Semi-Dispatch Cap (SDC) is in effect a semi-scheduled unit’s target output may not necessarily reflect the unconstrained potential.

When forecasting a unit’s unconstrained availability, the presence of a cap means output might not be indicative of availability:

- Availability in SDC periods is harder to forecast.

- When the SDC period ends dispatch targets might reflect availability that was poorly forecast.

Not forecasting in the presence of semi-dispatch cap periods caught Watt Clarity’s attention back in 2022. It’s not necessarily a bad thing, however the intervals during and soon after SDC periods are difficult to forecast and that is precisely when the best forecast is of great value when dispatching generators at the appropriate level.

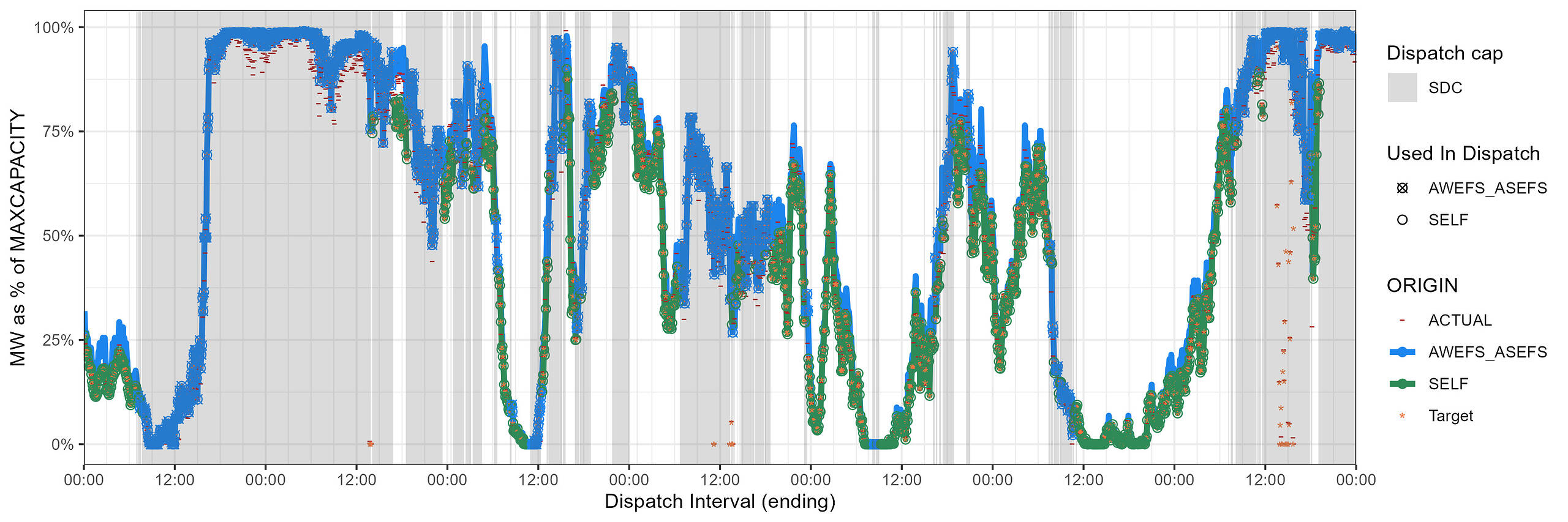

In the example below we see AWEFS_ASEFS forecasts being used in dispatch while the semi-dispatch cap is in place.

The blue circles represent when the AWEFS_ASEFS forecasts used in dispatch and these align closely with semi-dispatch cap periods.

Green circles indicate the self-forecast was used. It is a one week-long period because that is the duration of the ‘short’ performance assessment period.

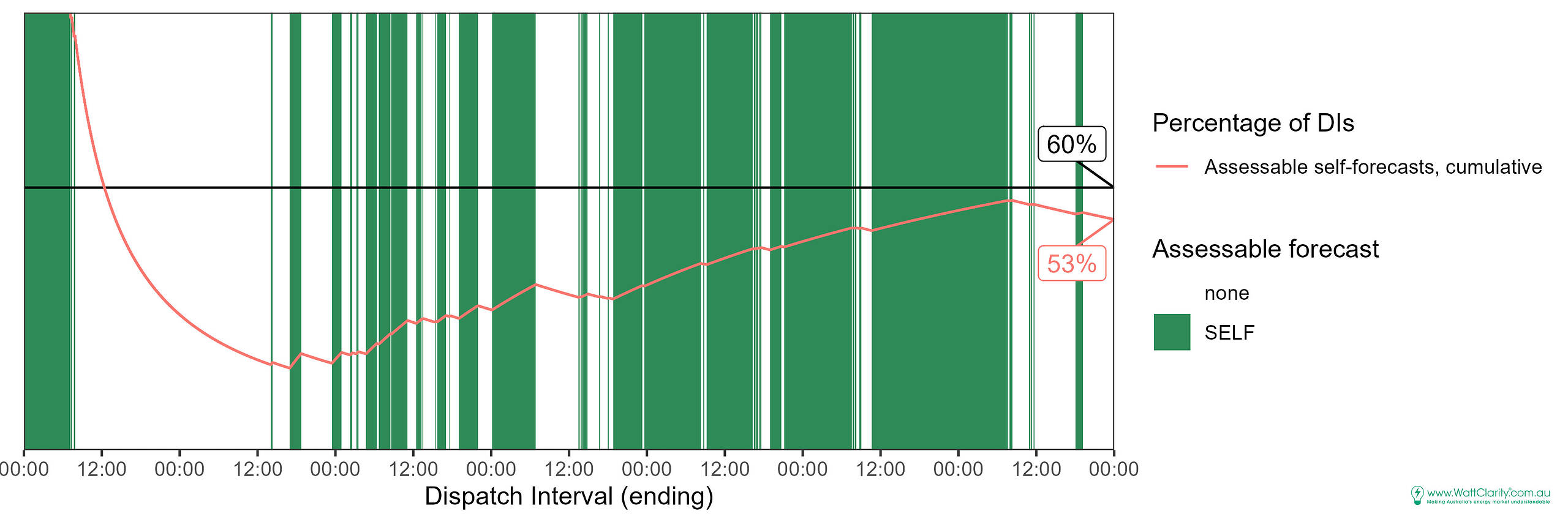

60% of intervals are needed for assessment

Weekly performance assessments drive improvement in self-forecasting systems and good accuracy over the long-term.

When the percentage of eligible self-forecasts drops below 60% there are said to be insufficient intervals to conduct a performance assessment.

Now, there is more than one pathway through the weekly performance assessment procedure. We’ve investigated that before.

Yet, theoretically, if a self-forecasting system never offers forecasts for more than 60% of intervals it may perpetually skip assessment and the system could continue for use unsuppressed by AEMO. Even if performance is poor.

The week above is an example of a system that didn’t meet the 60% threshold. It is clearer in the chart below.

During this week the percentage of assessable intervals was 53%.

In this case, there is no information to suggest that falling short of the 60% requirement for forecast assessment is a primary intention of the forecasting system. And we aren’t assessing performance in this article.

Rather, the system simply appears to avoid SDC periods and there were many of those in the week. It does this using the self-suppression option that is available. It is encouraged to be used for accuracy reasons:

- “AEMO encourages the SF provider to continually monitor the quality of its self-forecasts and proactively suppress them from use in dispatch if determined to be inaccurate.” (AEMO participant self forecasting FAQ of 2023).

However, there is a significant loss of control in availability levels when this approach is taken as a default behaviour (because of SDCs), rather than for case-by-case accuracy reasons.

The benefits of self-forecasting, being the benefits of more accurate availabilities, are destined to be unrealised when the system is suppressed for long periods.

Be the first to comment on "Examples of self-forecasting behaviours – part 4 – avoiding SDC periods"