The Retailer Reliability Obligation (RRO) is a complex administrative accounting framework overseen by the Australian Energy Regulator (AER) which places major compliance burdens primarily on retailers, but also generators, large customers and the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO).

Its objective is to force all load to be contracted, supposedly providing the consistent cashflow to enough supply to provide reliability. When proposed, it was felt it would finally provide confidence to those stakeholders who don’t believe energy-only markets are reliable. Mandatory contracts between supply and demand might conceptually parallel a conventional, centrally-contracted capacity market.

But to enforce universal contracting in a real power system is hard, requiring a whole ecosystem of technocrats, compliance officers, and auditors. And it’s getting ever harder as we transition from traditional power stations supplying traditional customers. This ecosystem comes at great cost to the industry, funded by the wholesale and retail component of customers’ bills.

In achieving the objective of sating energy-only market doubters the RRO clearly failed. Before the it even came into force, NEM institutions were working on a more conventional physical capacity market, which itself was overtaken by direct government underwriting through the Capacity Investment Scheme (CIS) and various state schemes. And AEMO’s reliability intervention powers were retained and expanded.

The RRO emerged unexpectedly, in a political attempt to appease opponents to the National Energy Guarantee (NEG). Whilst the NEG imploded somehow the RRO survived. Yet it has never, as a standalone concept, been properly assessed for costs and benefits, and would seem unlikely to pass.

In the search for ways to reduce the customer price of electricity, an RRO repeal could be a quick win with few regrets outside those in the customer-funded ecosystem it created.

How did it come to be?

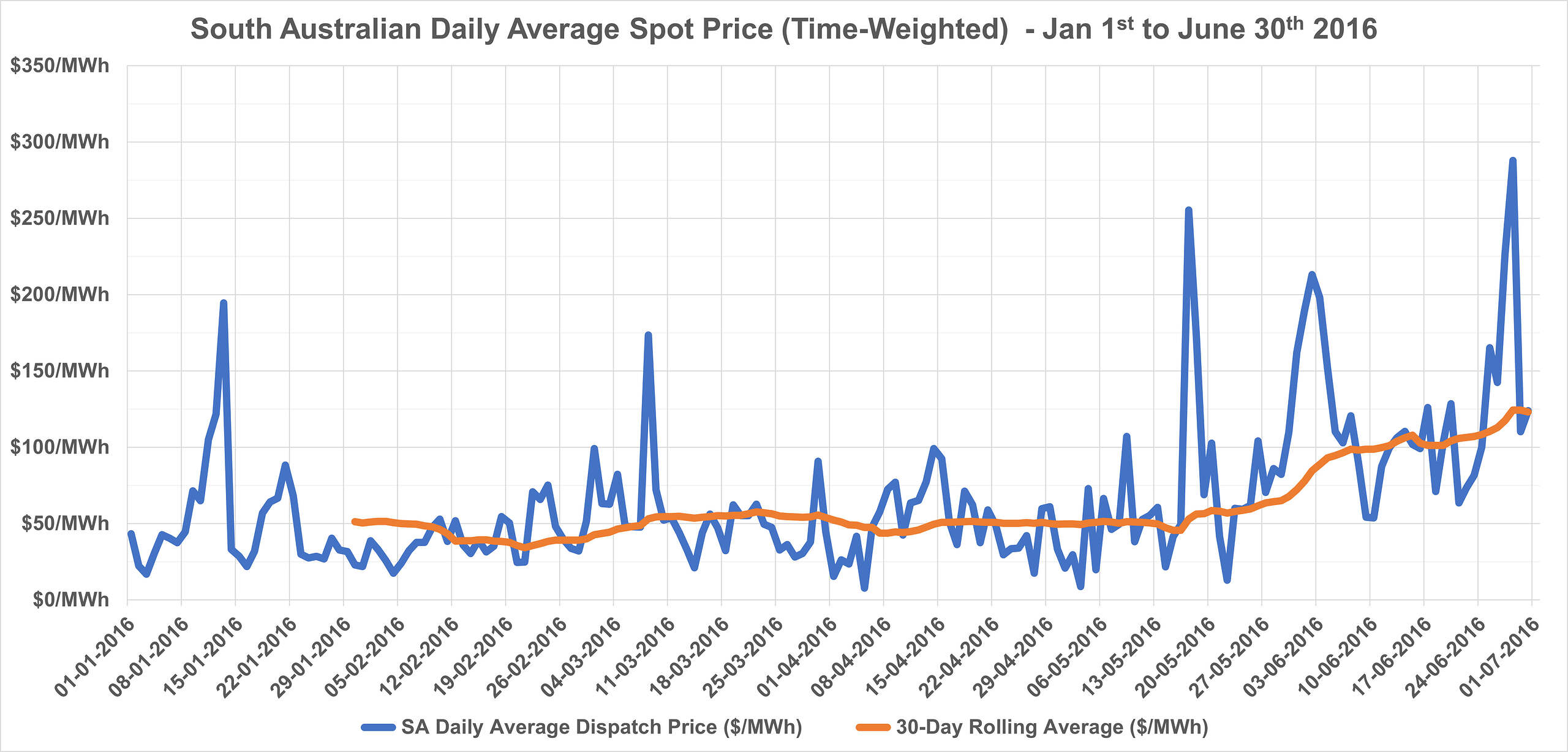

The seeds of the RRO began in the South Australian winter of 2016, several months before the system black. Northern Power station had closed in May, ahead of its previous schedule. At the same time, a large South Australian customer had declined to contract ahead its load, taking a gamble to buy from spot. Whilst we can never be certain, many link Northern’s early closure to this decision.

In June, a dunkleflaute event combined with an extended Victorian interconnector outage (ironically to expand its capacity) sent South Australian spot prices sky high.

The customer lost its gamble and found itself paying much more than expected, a harsh business lesson.

In the dismal science of economics, this outcome was a beneficial self-correction as the customer would not take the same risk again. But when a business loses money playing a market, in the eyes of the business, it is always the market, and not themselves, at fault. It put its state government under considerable pressure. In turn, the state demanded the NEM’s institutions come up with a fix, and mandatory contracting was suggested.

The RRO might have then disappeared into the deep bin of electricity market ideas that go nowhere, but in 2017 it received a unexpected boost. The federal government wanted to introduce the NEG, an emissions-intensity trading scheme widely supported in industry and mainstream politics. Minister Frydenberg needed something to deflect the predictable “lights will go out” cries from opponents to any form of carbon constraint, and the RRO emerged at just the right time. Despite there being no relationship between hedging practices and reducing the power system’s emissions intensity, they were stapled, allowing the NEG’s proponents to demonstrate their reliability focus. Industry understood this political deal and kept its RRO scepticism quiet in the hope that a NEG plus RRO package might yet end the carbon wars.

In 2018 the NEG collapsed spectacularly in Malcolm Turnbull’s second Julius Caesar moment. But by this time the RRO had been so strongly promoted that this part of the ship did not go down with its captain. The RRO sailed on as a stand-alone without ever being properly scrutinised. After all, who can say they oppose reliability?

The industry then embarked on the great effort of designing the detail of the RRO. The RRO had been conceived from an image of firm, conventional generators selling standard contracts to meet retailers’ deterministic peak loads. If the world were thus, you could just add up a retailer’s contracted megawatts and compare to its peak load in a spreadsheet. However, it was soon discovered that the real world is probabilistic, with a whole range of generation technologies, and that risks are managed in myriads of bespoke ways. This is a wonderful thing, the types of innovation that two decades of the market had fostered.

The triggers, the standard, and the ministers’ over-rides

The original RRO was designed only as a mechanism that would trigger only after consistent forecasts outside the reliability standard. If an AEMO forecast 3 years and 3 months ahead (T-3) is outside the standard, then several obligations on the industry arise. If the excursion remains in a forecast 15 months ahead (T-1), then the more substantial RRO compliance obligations on retailers are triggered.

This is a “double-gate”, a high hurdle that would rarely be met. However, under jurisdictional and AEMO pressure, the hurdle was soon lowered.

Firstly, the NEM’s Reliability Standard of 0.002% unserved energy, equivalent to a customer average of 10.5 minutes per year off supply, which had always been promoted by the Reliability Panel as the efficient optimum, was replaced with the highly conservative “Interim” standard of 0.0006%, or 3.1 minutes. Thus, triggers became more likely.

Secondly, the South Australian government disagreed with the double-gate and having failed to lobby it out of the design, demanded a derogation that allowed their minister to simply invoke the first T-3 gate in their region at will. Other jurisdictions soon wanted the same, so the RRO was changed to allow any minister to declare their region at risk, regardless of what the actual forecasts say, which leaves one now wondering the point of the first gate.

Thus, the RRO is now likely to be active in much more benign conditions than was initially envisaged, creating repeated costs that consumers are funding.

Converting probabilities into deterministic megawatts

When T-1 is triggered, retailers must begin reporting their net contract positions to the AER which will ultimately be compared for adequacy against their customer “peak load”. This is much, much more intricate than it sounds at first glance, and the below touches on just some of the challenges.

Firstly, most retailers have some of their own generation that they use to support customers. The RRO sees this as a “long” contract position, but of course some generator technologies are firmer than others and discounting is used. Capacity from demand-side response, settlement residue instruments, and energy-limited capacity such as storage can be claimed, each with different levels of “firmness”. As the RRO must be fed with a one-dimensional deterministic megawatt quantity, there is not much choice but to make crass simplifications when doing all this, which, given the industry’s growing reliance on these sources, provides little confidence that the final numbers mean very much at all to the true reliability of the power system.

Secondly, there are many varied contract instruments used by the industry, from standard exchange-traded instruments to highly bespoke long-term structured deals. The AER have come up with complex guidelines to try to turn these into simple net megawatts, but they realise that this can’t possibly correctly represent everything, so they allow retailers to determine their own methodology, subject to an audit.

Thirdly, there is no one number for a retailer’s “peak load”. The best each retailer can do ahead of time is develop a probabilistic distribution based on their best understanding and judgement. If the actual measured load turns out to be at an extreme of the distribution, we will never know if the distribution was wrong, or that we just saw an extreme event.

The way the RRO deals with this is that if the actual peak demand for a triggered season falls below AEMO’s 50 percent Probability of Exceedance (PoE) region forecast, which should be half of the years, then compliance is not assessed and all the hard work collecting RRO data is discarded. If, however, the actual peak load is measured at, say, 105 percent of AEMO’s 50 percent POE forecast, then each retailer’s load exposure becomes their actual load measured at that time divided by 1.05. This is intended to indicate a fair 50 percent PoE to which the retailer should at least be contracted.

Whilst this expost adjustment is probably the only fair thing that could be done, if the power system were only being invested to meet a 50 percent PoE demand, it would get nowhere near the interim reliability standard. That does not suggest that 50 percent PoE contract coverage necessarily implies an unreliable system, but rather demonstrates how a mathematical link cannot be made between market contracts and a probabilistic reliability standard. This leaves one wondering why we pretend a link can be made by undertaking the burdensome exercise of the RRO.

When all the above numbers are crunched it is unlikely, but still conceivable, that a retailer’s net contract position falls below their expost determined 50 percent PoE. If so, the non-compliant retailer picks up some of AEMO’s intervention costs. This is an unrelated number, because AEMO is driving to a very different objective when it intervenes. Its unpredictability may be intentional, as retailers can’t forecast the penalty for being non-compliant, so presumably they’ll err on the side of caution.

Market Liquidity Obligation (MLO)

When T-3 is triggered, the larger generation portfolios of that region are required to “make” a market by posting continuous bids and offers for standard contracts. In this feature the RRO’s objective has morphed from reliability into competition policy. It was justified as assisting smaller retailers to achieve compliance in the lead up to a T-1 but appears behind the South Australian government’s enthusiasm for ministerial triggers regardless of the reliability outlook.

Introducing a MLO through the RRO was poor regulatory practice. If there is a real competition concern in some regions, then it should be explicitly assessed on its merits and targeted action taken. Instead, a competition rule has been “tacked on” to a complex reliability mechanism without any evidentiary justification nor certainty that it is the right solution for the perceived problem.

What is the point of the RRO?

The supposed objective of the RRO is that a prudently hedged market is likely to be a reliable market. However, with a high NEM price cap and financiers demanding prudence in their investments, one would expect the market to be already prudently hedged without the AER having to go through everyone’s books. Importantly, as the prudence is self-assessed by those taking the actual financial risk, you can be sure it will uncover a clearer picture than an AER procedure ever could.

In contrast, when all the assumptions and simplifications that go into calculating a deterministic RRO net contract position are contemplated, it is difficult to gain much confidence that the outcome means much at all. And a minded retailer should have not too much difficulty in biasing the many judgemental matters towards a more favourable representation.

And even if it were possible to produce reasonable numbers, one wonders why prudently hedged retailers necessarily implies a reliable power system? In the end, retailers only need to show evidence of financial contracts to meet the RRO. The RRO doesn’t require evidence that the contract seller has firm physical capacity. The seller may simply being taking a short financial risk themselves. A naked seller of contracts is taking the same financial risk as an unhedged retailer and identically contributing to an unreliable power system. So, if there really is an incentive for imprudent financial risk taking that must be stamped out, has the RRO not simply moved the incentive upstream?

The doubters of energy-only markets saw this paradox immediately and started work on physical capacity mechanisms before the RRO was even in place. Then this was superseded by the even more centrally directed CIS and state processes. Meanwhile AEMO’s intervention activities have continued to expand.

Hence the RRO failed in its objective of providing reliability confidence in the existing energy-only market, which leaves one wondering why the industry continues to bother with it?

How can we get rid of it?

Conceptually, the entire RRO architecture could simply be deleted at the stroke of a pen without any physical or legal repercussions, except of course to the small army of functionaries in institutions and the industry needed to keep it ticking over. Unfortunately, because of the unusual way it was introduced, the RRO exists in the National Electricity Law. This complicates its repeal because more than a Rule Change is needed. It will need advocacy of multiple institutions and jurisdictions to get it undone.

This is not something that the industry will do, as after all, the industry doesn’t ultimately pay for it. Like all industry inefficiencies, it is funded up by customers in their bills. Abolishing the RRO seems like an obvious reform that could reduce consumer prices without any downsides to them, but it will need customer representatives to champion it.

About our Guest Author

|

Ben Skinner is an energy industry veteran, beginning as an electrical engineer in Victorian power system control, including on shift as a generation dispatcher. As the NEM started he was heading up the spot trading desk of a generation portfolio, but in time moved to market design and regulation. From 2008 he spent a decade as a specialist within NEMMCO/AEMO, principally engaging with government on environmental policy. In 2017 he returned to industry representation with 6 years as GM Policy for the Australian Energy Council, which he concluded in late 2023.

You can find Ben on LinkedIn here. |

What a mess – and given that the population is growing out of control and there doesn’t appear to be any believable figures for the additional generation (firmed?) necessary for charging more and more EVs, “system blacks” appear unavoidable.

I agree with the conclusions regarding the RRO, but the first section of this article misrepresents history.

Once Northern PS committed to closing, there was only one generator that could have feasibly supplied that large customer load. Realising this, that generator sought to extort the customer as much as possible, demanding a price well above market rates. The customer refused and took the risk of floating on the spot market, and the generator in question punished them for this decision, withdrawing capacity in order to induce volatility. You can argue this was a reckless gamble, but it wasn’t necessarily a bad one – a week of volatility is ultimately easier to stomach than years of overpriced power.

This wasn’t the impetus for the RRO, however. Eight months later, that same generator, still seeking to extort South Australian customers, withdrew part of its capacity for the summer, leading to controlled blackouts in SA. This is what drove the creation of the RRO, the argument being that blackouts could’ve been avoided if customers had given in to the generator’s demands; that AEMO later took the generator to court for misrepresenting their availability seems to have been overlooked.

Many people recognized that this was actually a competition issue – if multiple generators had been competing to win customers, it’s unlikely that a large portion of load would’ve gone uncontracted. The RRO does nothing to resolve that problem and, in fact, makes it worse, as it reduces customer bargaining power. The MLO was stitched on to the RRO in an effort to counteract that effect, though who knows if it’s worked.

As the article points out, none of this has anything to do with actual system reliability, which is a bigger issue than the level of contracting over a short period.

Thanks Teffy, you’ve been part of an experience to which I was unaware.

The period I was referring to was the period immediately prior to the decision to close Northern early and offers by its owners to sell contracts from it. I gather you are referring to the challenging competitive situation after it had committed to close. I imagine that would have been very difficult time indeed for customers.

The general industry narrative, however, that was used to justify the construction of the RRO, referred to decisions of the customer being made prior to the decision to close northern.

In the end, this is all ancient history, based on peoples, subjective recollections of a series of negotiations. my point in bringing it and the neg up is just to show that the RRO was an accident of random history, rather than an outcome of any thoughtful design.

So according to Teffy- who seems to be mixing up several years – generators stop running for a couple of years to make money. Yeah, righto. Seems like a classic case of a customer expecting the market to stay static as they made a bad call. If you want prices to stay low, lock in a contract. If you don’t the plant that pushes down spot prices won’t run, and prices will rise. It’s not hard Teffy.

Bravo Ben – abolish it.

Fantastic article, Ben. Could I please query one detail though. If the interim unserved energy reliability standard is 0.006% and the old was 0.002%, then the interim would be less conservative than the old. But, I think it’s simply a typo, and the interim standard is 0.0006%.

Frustrating to hear that a Rule change can’t repeal this because it’s in the NEL. Hopefully some traction can be gained with customer representatives.

Well spotted Trevor and correct. An important zero has gone missing. We’ll get that fixed.