If you can answer both those questions then you should probably have written this post, not me.

If the NEM didn’t already have enough TLAs (three letter acronyms), the Retailer Reliability Obligation (RRO) may fix that problem. It emerged from the demise of another better-known TLA, namely –

The NEG: not quite as dead as you thought

Most readers will have heard of the ill-fated NEG (National Energy Guarantee), the energy policy proposed under Malcolm Turnbull’s government to “integrate climate and energy policy” in a framework imposing joint mechanisms on the electricity sector for “guaranteeing”:

- emissions reduction

- supply reliability

through some pretty complex requirements on the contracting activity undertaken by wholesale market participants.

The primary role of these ‘hedge contracts’ in the NEM is to manage the risk exposures that both sides of the market (generators, and retailers supplying end users) have to the volatile spot price. Up until recently there had been no particular energy market regulatory requirement on what level and what kind of contracts participants might decide to hold, with the idea being that market forces and risk tolerances would naturally guide participants towards sensible and rational assembly of contract portfolios for managing their businesses.

The emissions part of the NEG dealt with the carbon-intensity “embedded” in contracts ultimately sourced from different generators, and would have required retailers to achieve target levels of carbon-intensity across their overall portfolio of purchases, reducing over time. The reliability part of the NEG was intended to force the same retailers to hold sufficient “firm” contracts that could somehow be linked to physical generation, so as to financially hedge their share of (ie their customers’ aggregate contribution to) maximum system demand. The idea being that prescribing a sufficiently high level of demand from retailers needing to buy such contracts would ensure that enough “firm” / dispatchable generation would be built to maintain system reliability.

As we all know, unease within the government caucus room over the emissions leg of the NEG triggered events leading not to lower electricity emissions but to the emission of PM Turnbull from his position. The NEG itself was abandoned soon afterwards.

Less well known outside the confines of the industry was the survival of the NEG ‘s other leg, under a probably-hasty rebranding as the “Retailer Reliability Obligation“.

The RRO

The basic idea of the RRO is that if a system reliability gap is forecast in in a NEM region for some period, then requirements kick in for retailers, who purchase electricity in the wholesale market on behalf of their customers, to hold sufficient volumes of “qualifying contracts” over that period to hedge their share of maximum system demand.

That sentence masks an enormous amount of complexity in how when and by whom these things are assessed, measured, reported etc.

Teams of people from regulators and industry participants beavered away under the aegis of the ESB (Energy Security Board, who had dreamed up the whole NEG idea in the first place) to produce a complete framework for the RRO, which was signed off in the middle of last year by the COAG (Council of Australian Governments) Energy Council of State and Federal Energy Ministers, and rolled into the NEL (National Electricity Law) and Rules. I haven’t looked at the relevant sections but I guess they run to dozens and dozens of pages, and associated guidelines and procedures produced by the AER (Australian Energy Regulator) and AEMO run to many hundred more.

I won’t begin to attempt to cover much of that detail in this post, but have put together a very simplified table of key steps in the RRO process and timeline. In theory, it all starts when AEMO’s ESOO (Electricity Statement of Opportunities) runs forecasts of future reliability and in particular whether the NEM’s Reliability Standard of no more than 0.002% USE or “expected unserved energy” (more on that here) is met in each region. If it isn’t, that constitutes a Reliability Gap that kicks off the whole RRO box of tricks.

| Timing (relative to start of Reliability Gap) |

Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 3 years + 3 months | T-3 Reliability Instrument Request | If AEMO identifies a Reliability Gap at least 39 months ahead, it requests the AER to issue a T-3 Reliability Instrument. |

| 3 years + 1 month | T-3 Reliability Instrument | AER assesses AEMO’s request and may make a determination to issue the T-3 Reliability Instrument. This triggers various RRO compliance mechanisms, in particular the Market Liquidity Obligation (MLO) and Voluntary Book-Build (VBB) process. |

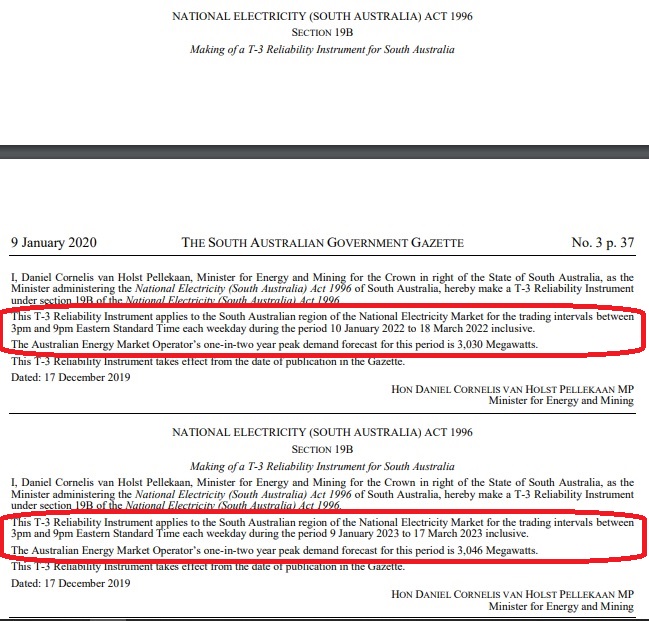

| [up to 15 months] | T-3 Reliability Instrument [SA Minister for Energy] | The SA Minister for Energy may unilaterally trigger the RRO in South Australia by issuing a T-3 Reliability Instrument. Until 1 July 2022 the Minister can do this with a minimum notice time of 15 months. After 1 July 2022 the minimum notice time is 3 years. The Minister is required to consult with AEMO and the AER. |

| From ~1 month after T-3 Reliability Instrument | Market Liquidity Obligation applies to large suppliers in the relevant region.

AEMO-run Voluntary Book-Build process commences |

The MLO requires specified large generators in the relevant region to make available on a trading exchange (initially the ASX Energy platform) small-volume contracts covering the period of the Reliability Gap, enabling smaller buyers affected by the RRO to source suitable contract cover if required. The MLO applies to these generators until they have sold a specified volume of contracts or until Contract Position Day (see below).

The VBB is a simple bulletin-board style platform and process operated by AEMO for matching potential buyers and sellers of qualifying contracts for the Reliability Gap period. It provides another mechanism for buyers to source contracts and for potential new market entrants to find interested offtakers. |

| 15 months | T-1 Reliability Instrument Request | If AEMO confirms that the Reliability Gap still exists, it must request the AER to issue a T-1 Reliability Instrument. This applies regardless of whether the RRO was initially triggered via an AEMO request or by the SA Minister. The SA Minister cannot issue or request a T-1 Reliability Instrument. |

| 13 months | T-1 Reliability Instrument | AER assesses AEMO’s request and may make a determination to issue the T-1 Reliability Instrument. If issued, AEMO may commence procuring Reliability and Emergency Reserve Trader (RERT) resources. |

| 12 months [6 months for short notice trigger by SA Minister] |

Contract Position Day (CPD) | Liable retailers (and any large end use customers who “opt-in” to manage their own RRO position) are required to report on the volume of Qualifying Contracts held as of this date against their market exposure for the Reliability Gap period. |

| 0 | Start of Reliability Gap period | The T-3 and T-1 Reliability Instruments specify start and end dates of the Reliability Gap and which Trading Intervals (half hour settlement periods) within those dates are subject to the RRO obligations. |

| after Reliability Gap period | Compliance Assessment | If actual demand in the nominated Reliability Gap exceeds AEMO’s 1 in 2 year (POE 50) maximum demand forecast, AER assesses if liable parties held sufficient qualifying contract volumes to cover their RRO obligations. Parties who did not hold sufficient volume may be liable for compliance penalties of $1M-10M, and a share of RERT and other related costs up to $100M. |

Yes Minister

If you managed to read that table carefully, you may have noticed the part where the RRO isn’t triggered by AEMO’s ESOO, with its extensive monte-carlo modelling and other bells and whistles, but can be initiated by the South Australian Minister for Energy waking up one morning and deciding they’re a bit worried about future reliability, to wit:

OK, that’s flippant; the SA Minister is required to consult with AEMO and the AER, but as part of a special deal done at COAG to get the whole RRO mechanism through, South Australia alone amongst the NEM states was granted unilateral ability to trigger the first part of the RRO process, ie issuing a “T-3 Reliability Instrument”, which they have now done for two separate periods.

Whether this runs its full course into actual compliance requirements for retailers to hold qualifying contracts for those periods in Q1 2022 and Q1 2023 is subject to a critical second gateway, namely the issue of a T-1 Reliability Instrument. This can only happen if AEMO – and not the SA Minister – confirms that there is a Reliability Gap 15 months out. For Q1 2022 this would correspond to around the timing of AEMO’s August 2020 ESOO, which will be watched with great interest.

In press comments, Minister van Holst Pellekaan described the measure as “precautionary”, adding

“This will provide AEMO with greater flexibility. Should AEMO’s forecasts one year out from these periods show a reliability gap, retailers will be required to have enough electricity supply contracts in place or face penalties. AEMO would also be able to procure additional reserves as a safety net.”

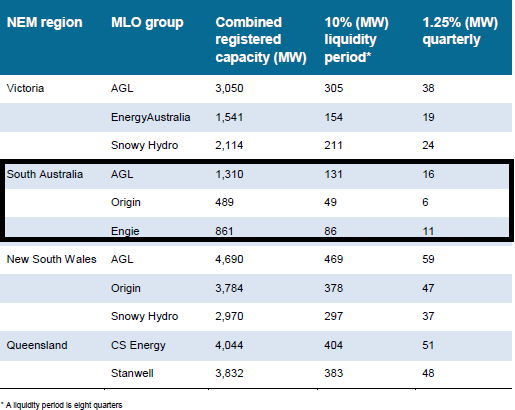

Notwithstanding that, the Minister’s issue of two T-3 Instruments has triggered the MLO (Market Liquidity Obligation) which will apply in South Australia to AGL, Engie, and Origin as the largest generation owners in that region. These three parties will now be required to offer via the ASX Energy platform small-volume futures contracts for periods covering the two Reliability Gap periods specified by the Minister’s notice. Details of how the MLO operates can be found in the AER’s interim guideline, which contains the following table:

The last two columns in that table specify net volumes of contracts covering each Reliability Gap period which these parties would need to sell in aggregate and per quarter, before being relieved of the obligation to offer further contracts in total, and during any quarter.

The idea behind the MLO is that it may enable smaller retailers with less bargaining power or access to their own generation to source at least some of their RRO contract requirements from major suppliers through a relatively transparent process that seeks to ensure a minimum level of market liquidity.

Also triggered is a VBB or “voluntary book build” process under which AEMO facilitates discovery / matching (think Tinder for energy markets) of interested buyers and sellers who may not be in a position to immediately contract.

Mind The Gap

Now that we fully (?) understand the RRO process, what is the market data we can see actually saying about supply reliability in South Australia?

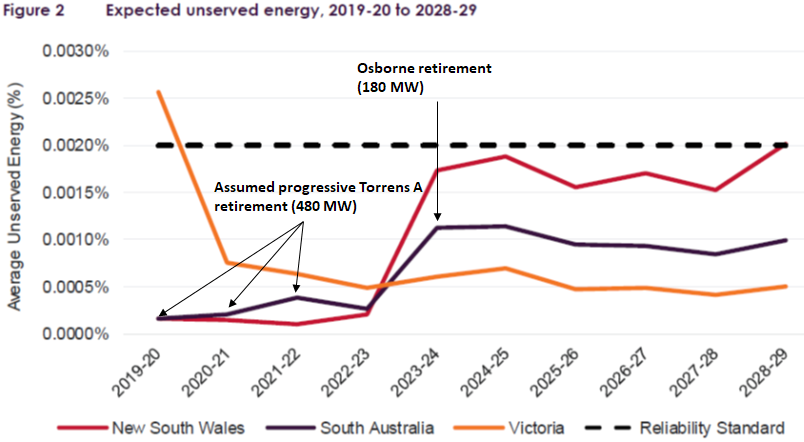

Let’s start with AEMO’s 2019 ESOO, which didn’t identify a Reliability Gap – the relevant chart is here, with a few annotations:

This shows SA’s assessed reliability sitting comfortably within the Reliability Standard for the summers of 2021-22 and 2022-23, even with the then-forecast retirement timing for Torrens Island A power station (which has since been extended, with two (of four) units retiring after this summer and one further unit after each of Q1 2021 and Q1 2022. ) Even with the further planned retirement of Osborne in 2023, assessed reliability remains within the Standard.

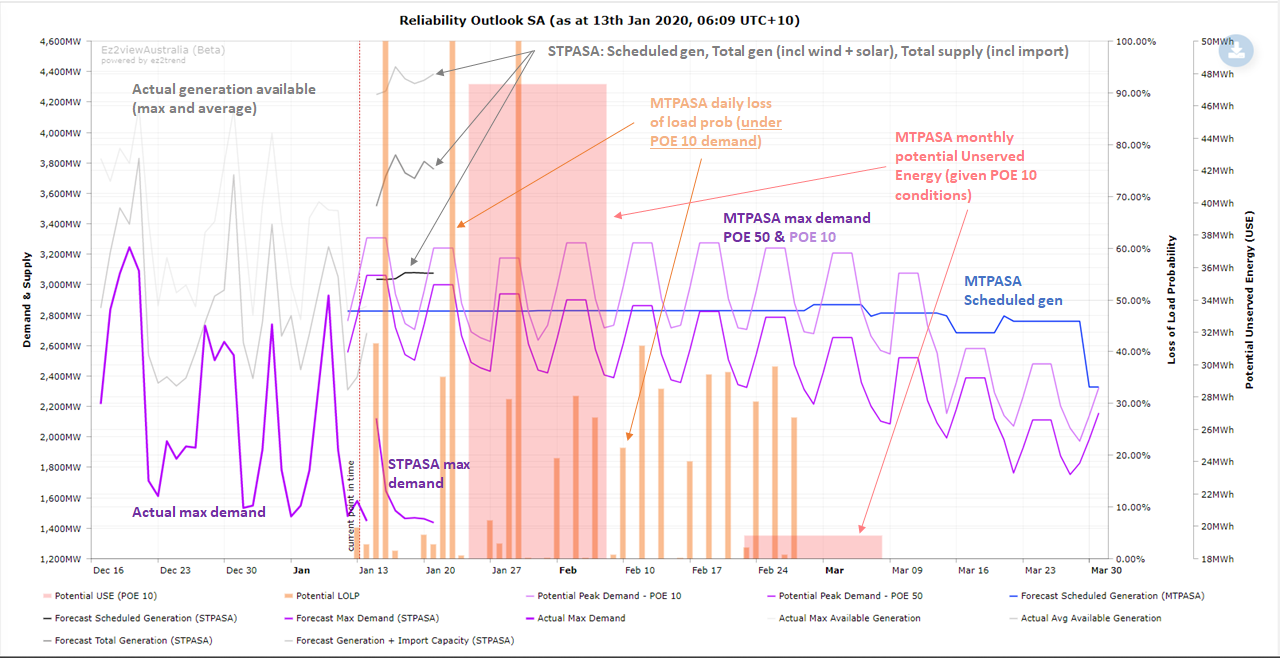

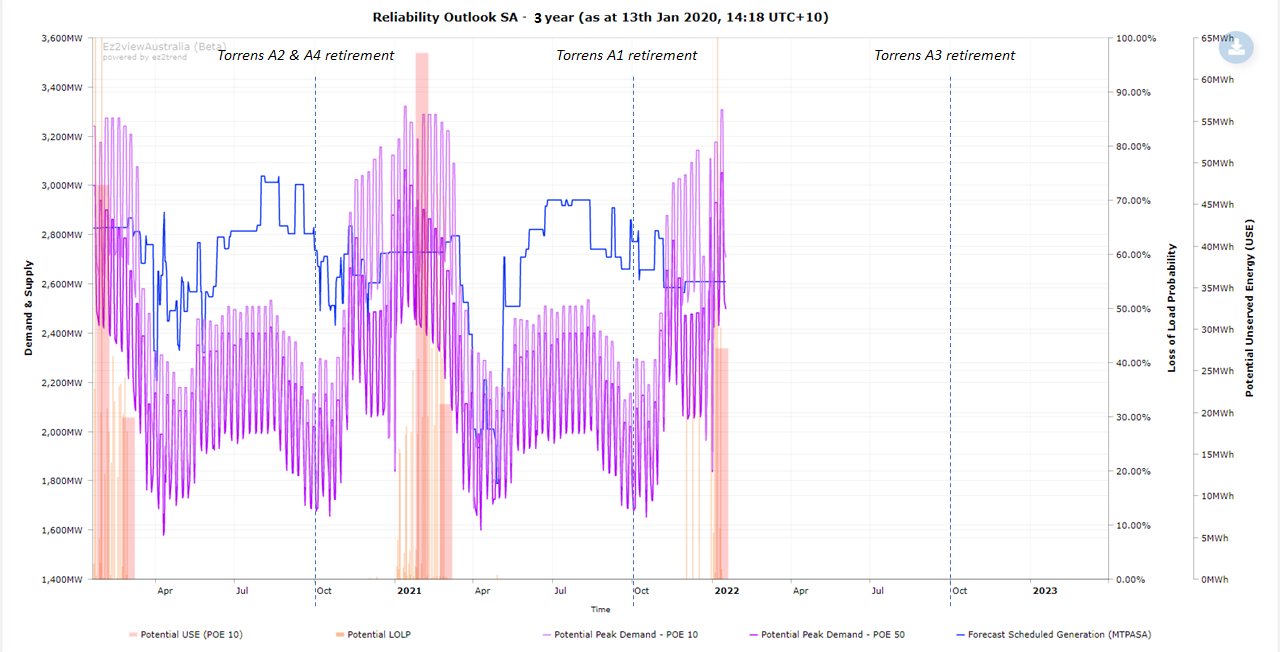

For reference, a more granular view of reliability for the current Q1 is provided by AEMO’s MTPASA data, produced by a modelling process similar to that used in the ESOO, shown here in an ez2view trend chart:

I’ve added to this chart for reference the last few weeks of actual demand and supply levels, and also AEMO’s short term (STPASA) projections covering the next week or so. Some salient points from this busy chart are:

- actual maximum demand in the week of December 16 last year reached over 3,200 MW, approaching AEMO’s whole-of-summer forecast for a 1 in 10 hot year of 3,274 MW. This was driven by extraordinarily hot conditions, but may have been one factor playing into the Minister’s decision.

- The STPASA projections for the current week ahead show much more moderate demands, reflecting fairly benign weather forecasts.

- Three STPASA supply projections are shown: Scheduled (dispatchable) generation, Scheduled + semi-scheduled (including forecast wind and large scale solar output), and adding in available interconnector support (Total supply).

- This highlights the difference between supply based on in-state dispatchable generation only (around 3,000 MW total), and total resources of nearly 4,400 MW. A key issue in reliability assessment is how much capacity the non-dispatchable generation and imports might actually contribute in a “worst-case” situation. The variability here is a major reason for AEMO running extensive probabilistic modelling to derive its ESOO (and MTPASA) reliability projections.

- The MTPASA supply and and demand data show much simpler and more limited projections covering only scheduled generation availability, and POE 50 (50% Probability of Exceedance, or 1 in 2 year) and POE 10 (1 in 10 year) maximum demand levels.

- So while “demand” appears to exceed “supply” across a lot of the MTPASA projection period:

- demands shown are maximum levels actually expected to be seen for a single half hour on a single peak day of summer: 1 year in 2 (POE 50), or 1 year in 10 (POE 10)

- supply includes no explicit contribution from large scale renewable generation or imports from Victoria

- the actual full variability of demand and supply from all sources is taken up “behind the scenes” in AEMO’s probabilistic modelling

- MTPASA reliability indicators produced by this modelling are given by the monthly USE (Unserved Energy) projections (wide pink bars, in MWh) – skipping through some complexities, these values equate to about 0.0001% on the same reliability scale used in the previous ESOO plot, versus the standard of 0.002%.

- Finally those worrying-looking LoLP (Loss of Load Probability) levels shown at up to 100% are indicators of relative not absolute risk – they are projections of the need to call on out-of-market resources or (worst-case) involuntary load shedding if the 1 in 10 year maximum demand actually turned up on each day in the projection.

With that background on how to read these charts, let’s widen out the view to include Q1 2022 and Q1 2023:

If you noticed that most of Q1 2022 and all of Q1 2023 are missing, do not adjust your browser. AEMO currently doesn’t publish MTPASA projections for longer than two years ahead, so we can see only a small part of what’s happening in the first Reliability Gap period triggered by the Minister and nothing at all in the second period. On what we can see, there is some net step down (about 200 MW) in scheduled generation capacity between Q1 2020 and Q1 2022 – which would be Torrens Island unit retirements (360 MW) net of some capacity additions, so prima facie we would expect to see at least marginally higher projected USE in Q1 2022 and Q1 2023, consistent with the ESOO reliability projection.

The Market View (?)

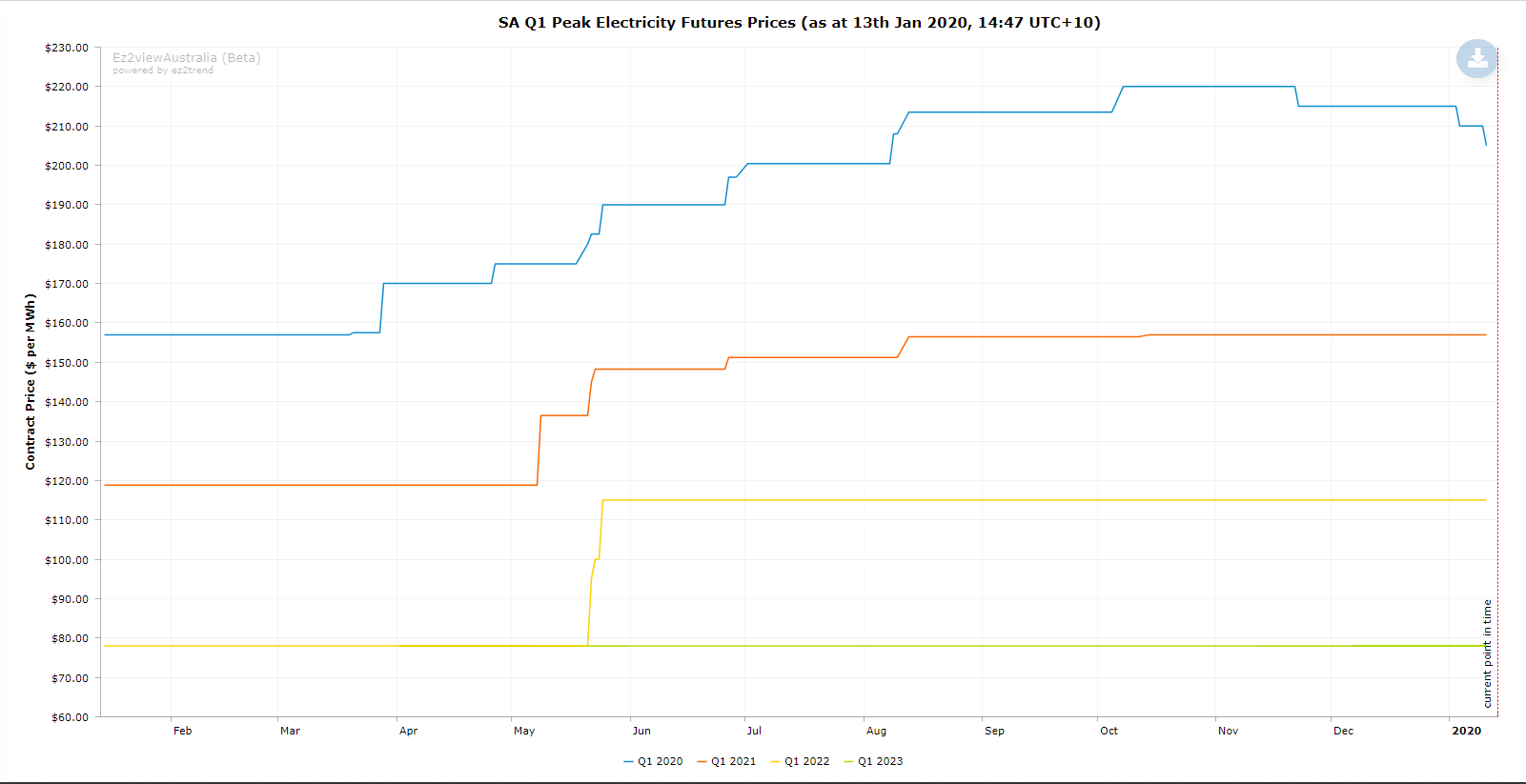

Absent any further insight from AEMO data, we can see if ASX Energy futures prices for South Australia provide any insight into market views on reliability. Here are the “trading” prices for Q1 Peak contracts (covering 7am to 10pm on working days) for each of 2020 through 2023:

These may seem to show a market progressively more relaxed about future summers, with Q1 2023 apparently being priced way under the current summer quarter. This would indicate a market expecting significant spot price falls, little volatility and by extension much more robust reliability.

But in fact, the completely flat price path for that contract year and also the relative absence of movements in the 2022 and even 2021 quarters perhaps illustrate another reason for the SA Minister’s action – these contracts are notoriously illiquid in South Australia relative to other NEM regions (and even there, liquidity in out years is typically patchy at best). So the prices charted are in all likelihood “stale”. Behind the scenes in the bilateral brokered market for “over the counter” contracts, there may be quite different prices, but these are not readily available to those outside the market.

By triggering the RRO and hence MLO, which will force the large suppliers to “make a market” in these or very similar contracts, the Minister and the rest of us may get actually get to see a more realistic picture of the market view on reliability, expressed through traded contract prices. Not that that by itself would be anywhere near a full and sufficient justification for the Minister’s decision.

——————————————-

About our Guest Author

|

Allan O’Neil has worked in Australia’s wholesale energy markets since their creation in the mid-1990’s, in trading, risk management, forecasting and analytical roles with major NEM electricity and gas retail and generation companies.

He is now an independent energy markets consultant, working with clients on projects across a spectrum of wholesale, retail, electricity and gas issues. You can view Allan’s LinkedIn profile here. Allan will be sporadically reviewing market events here on WattClarity Allan has also begun providing an on-site educational service covering how spot prices are set in the NEM, and other important aspects of the physical electricity market – further details here. |

“Teams of people from regulators and industry participants beavered away under the aegis of the ESB………… I haven’t looked at the relevant sections but I guess they run to dozens and dozens of pages, and associated guidelines and procedures produced by the AER (Australian Energy Regulator) and AEMO run to many hundred more.”

Oh dear when what we consumers really want is tenderers of electrons to the communal grid to be able to reasonably guarantee them 24/7/365 both with their frequency and voltage or else keep them. A level playing field methinks but perhaps I’m being all too simple minded here in the face of great complexity?

Very Good Article on very note worthy topic.