Load shedding in South Australia on Wednesday 8 February and successive ‘close shaves’ in NSW and Queensland as the heatwave spread north have exposed serious weaknesses in the national electricity market (NEM).

For some time now, it has been fashionable to blame South Australia’s near 40 per cent renewable (wind) generation mix for outages in that state. However, reliability problems in regions with much less renewable generation underline that the challenges facing the power system are much more complex and extend far beyond South Australia.

The NEM’s ‘energy only’ market design means that generators get paid when they are called to run, but not otherwise. It was and remains a fundamentally sound basis for organising generation markets.[1] However, the consequences of some poorly-conceived interventions in that market design are now starting to show.

At the time of its instigation, the bi-partisan renewable energy target (RET) seemed straight-forward: mandate that purchasers of wholesale electricity buy an increasing proportion from renewable sources, and impose stiff penalties for non-compliance. Few appreciated that subsidising one form of generation amounted to imposing a tax on all others.

Compounded by weak demand growth since 2009, the RET has driven a steady exodus of fossil fuel generators from the market. Some aging, CO2 heavy, coal-fired plants had in any case passed their time and needed to go if carbon reduction targets are to be met. But several much newer, CO2 light, gas-fired plants have also been mothballed – squeezed between high domestic gas prices and electricity market revenues deflated by subsidised wind turbines.

With the planned closure of the giant 1600 MW Hazelwood plant next month, market rules and operating protocols must be adapted quickly if the past week’s problems are not to be much worse come the summer of 2017/18.

Here are five suggestions warranting close attention:

- The protocols and norms by which market operator AEMO makes decisions need careful review, so that the system is run more conservatively and with greater emphasis on the consequences of ‘getting it wrong’ – for example, in assessing capacity requirements in South Australia, AEMO assumes a contribution towards peak demand from wind of nine per cent, yet when demand was high last Wednesday the weather delivered only half that amount. On its face, a much more cautious approach is needed.

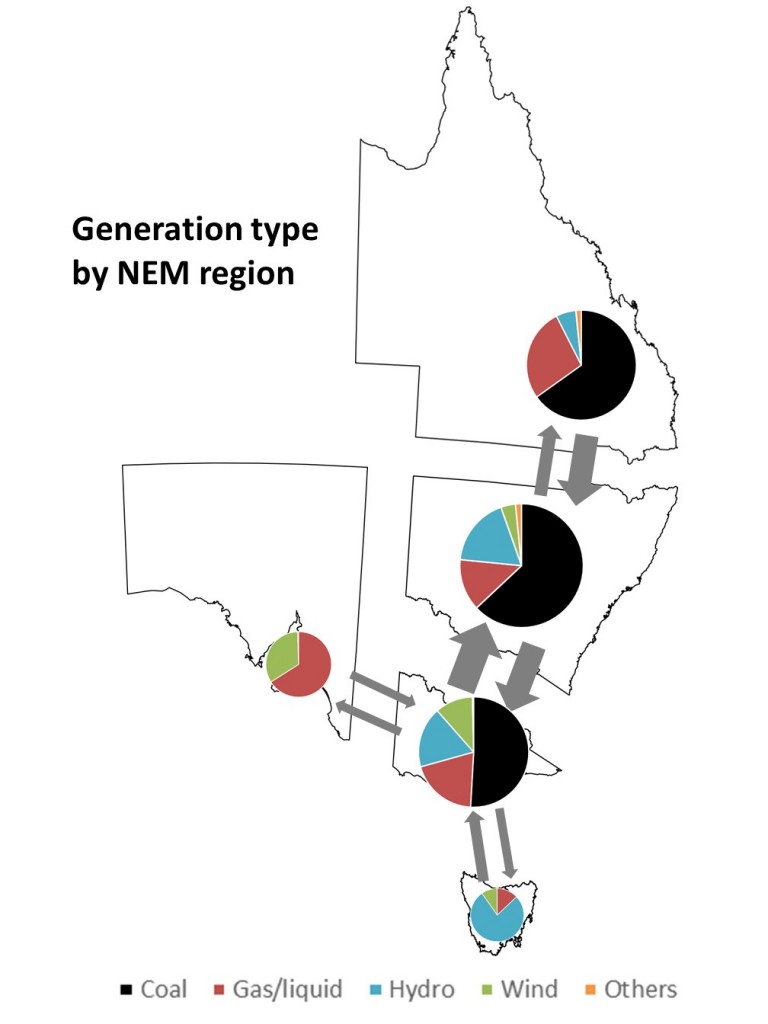

- Greater caution as to target levels of supply reliability would also assist the case for AEMO invoking its ‘reliability and emergency reserve trader’ powers more frequently and, longer term, for much stronger interconnection between NEM regions. Heatwaves rarely hit all of the south eastern states simultaneously, and providing for greater diversity of supply across regions is critical.

- The generator playing field must be levelled so that the structural disadvantage imposed by the RET on forms of generation that can be scheduled with very high reliability (eg, fossil-fuelled and solar-thermal units) is eliminated, thereby improving the incentives to invest in this form of capacity. There should be no need to throw out the energy-only market design, but there is opportunity for market-saving innovation, perhaps by introducing a price premium for output from scheduled generation, paid for by a discount on the output from semi-scheduled generators (mostly, wind) that only ‘turn up when they can’.

- The market price cap should be raised so that it more closely reflects the cost to customers of losing load, and encourages peaking plant to be more available – even if deployed for just a few days per year. For the energy only market design to work as intended, it must not prevent peak period prices from reflecting the high cost of load shedding or non-supply. Ensuring the demand side of the market can see and respond to high price events would also assist energy consumers to make informed choices on peak days.

- Lastly, the Victorian and NSW governments could assist by easing their moratoria on gas exploration and development, and facilitating arrangements that enable land-owners to share a greater proportion of the potential value of onshore gas reserves. Improved availability would take the pressure off domestic gas prices and strengthen the viability of gas-fired generation.

The first four of these measures would all add to the cost of generating and delivering electricity, and so the prices paid by consumers, while the fifth is also far from popular. However, the cost to consumers and the economy as a whole of an unreliable power system is a much higher price to pay. Decarbonising our energy system involves hard choices, and time is running out for those choices to be made.

Greg Houston was interviewed in relation to the challenges facing the NEM on ABC’s 7.30, Monday 13 February. See: http://www.abc.net.au/7.30/content/2017/s4619264.htm

[1] By contrast, generators in Western Australia (not part of the eastern states market) get paid just for being available, and WA consumers now pay a high premium for capacity they do not need.

This article was originally published on LinkedIn.

|

Greg Houston is a founding partner of HoustonKemp.

He is an expert in the application of economics to assist high stakes decision-making in competition, finance, public policy and regulatory matters. You can view Greg’s LinkedIn profile here. |

-Flexible generation already gets a price premium and wind already gets a price discount.

-“AEMO supply reliability leads to interconnection” what?

-AEMO’s capacity contribution assessments had nothing to do with supply shortfalls in SA

This guy is just trying to drum up business by chucking all the keywords in one place.

Here’s one fix: Bipartisan policy then get out of the way.

What we need is proper planning for load shedding. Cutting supplies to an aluminium smelter should be a non-no. Strict measures to reduce demand and to stop demand growth, e.g. passive solar houses instead of energy hungry residential towers. There is also need to cap power consumption of households at the meter during peak periods.

High pool price spikes suggest system has reached its limits and/or there is market manipulation.

As for the 5 min bid stacks imagine we had auctioning of petrol at our filling stations every 5 minutes!

I agree with some of your points; however there is now a need to move towards a capacity market to ensure that capacity is always available.

This could be done by AEMO invoking its Reserve Trader Powers but they seem to have been missing in action on this to date.

I do not agree with raising VoLL.

if anything VoLL should be reduced. it adds a huge risk premium to the market and it has yet to achieve its stated aim of being a signal for new generation.

It should be abandoned in favor of a capacity market which values capacity, not just energy which may or may not be there when you need it.

“It should be abandoned in favor of a capacity market which values capacity, not just energy which may or may not be there when you need it.”

There are 2 parts to that overall emergent problem. The traditional but growing one of peak demand whereby aircon use is demanding 20% more generation and distribution capacity for a few weeks of the year in summer and that’s particularly correlated with Adel and Melb weather. In that respect it makes power bill sense to price accordingly i.e. consumers with aircons can choose lower prices if they sign on to having a smart meter that can demand manage their aircon compressor for 20% of the time or stick with full user pays. The other biggie now for consumers is getting reliable electrons anytime, summer and winter, regardless of smart metering in summer, but that’s where my level playing field policy comes in. Under that regime the AEMO will know exactly what amount of reliable electrons are available in total and so will all the market players with future planning and investment in mind. Not so with the current disastrous regime.

“There should be no need to throw out the energy-only market design, but there is opportunity for market-saving innovation, perhaps by introducing a price premium for output from scheduled generation, paid for by a discount on the output from semi-scheduled generators (mostly, wind) that only ‘turn up when they can’.”

The notion that some omniscient public servant can work out the optimal price premium and discount between reliable and unreliable electrons tendered to the grid is to believe I’m the second coming, which sounds fine to me if I’m paid according to my new station in life. Much wiser for mere mortals to set the level playing field and let the multitude of players work it out between themselves. Ipso facto that means EVERY tenderer of electrons to the communal grid can only tender up to a maximum they can guarantee 24/7 all year round and let the market work it out.

I don’t know what sort of cross transfers would eventuate with the only obvious level playing field outlined, but clearly fickle wind and solar would have to pay reliable thermal partners their just insurance premia in order to up their average tender quantities (wind had an average of 29% of installed output only in 2016 but what about all their dips below that line?) and/or invest in storage to achieve it. Let them work it out over time between themselves, or else vertically integrate their generation mix. All I want is reliable, despatchable electrons, with appropriate compensation if I don’t get them and judging by the political ruckus at present, I’m not alone.

The free-riding is easily demonstrated looking at wind output as a proportion of installed maximum output- http://anero.id/energy/wind-energy/2017/february

and astute observers will notice the below zero graph lines and perhaps be interested in switching the graph to MW top right.

In 2016 the average output in Australia was 29% which marries well with an oft quoted figure around 30% of installed output for wind energy in general. Simply draw a horizontal line at 30% and look at all the dips below that line and their negatives that wind generators would have to pay a despatchable thermal insurer to cover them (fast start peaking gas perhaps?)or else install storage to be able to use some of those peaks. Notice also that to the extent they rely on thermal to backstop/lift their tender levels that reduces thermal 24/7 all year round tender capacity by the same amount, but the bonus is the AEMO and all players then know the absolute level of reliable electrons that are possible and can plan investments against any rising overall demand with confidence. Not a hope in Hell of private enterprise doing that now with the wild roller coaster they’re on, but if you think public servants can do it better with our taxes, then you’re part of the problem. The problem being you aren’t looking at the big picture, but are instead stuck within your blinkered speciality like so many-

https://wattsupwiththat.com/2017/02/20/climate-science-and-climatology-specialization-and-generalization-forest-and-trees/

Unfortunately a national electricity grid knows no such bounds.

The owners of sparingly-used assets such as the Port Lincoln and Colongra power stations must be wondering why when those assets were required, they failed and were unable to bid into a a high-priced market. Inadequate testing prior to forecast demand peaks ? Perhaps the market operator should require twice yearly testing of their systems before the demand peaks in later summer and mid winter.