On Tuesday, Allan O’Neil published a piece here on WattClarity that was a look at the early returns of Stage 1 of Project Energy Connect (PEC). He concluded with the suggestion that PEC could lead to more: (1) counter-price flows, (2) negative residues, and (3) head scratching from market watchers like us.

Here I’ll be looking at a very specific interconnector behaviour we’ve been seeing lately – double and even triple cycles of interconnector auto-clamping to manage negative residues. In this article, I’ll aim to help readers understand the related arrangements, and provide some context about how these occurrences might compound once PEC Stage 2 eventually comes online.

Flows and Counter-Price Flows

Interconnectors link the five regions of the NEM together and they allow for the inter-regional transfer of electricity. Each interconnector has a dynamic import and export limit (i.e. to limit flow in each direction), which are recalculated every 5 minutes through the use of constraint equations.

The NEM has a ‘marginal cost’ design where a spot price is conceptually meant to represent the cost to meet the next megawatt of electricity demand in a region. Therefore when an interconnector is within limits, the next megawatt of electricity for the two regions on either side can come from the cheaper region (so prices for both regions should roughly align). When an interconnector hits a limit, prices separate – sometimes significantly – because the next megawatt for the more expensive region cannot come from the cheaper region.

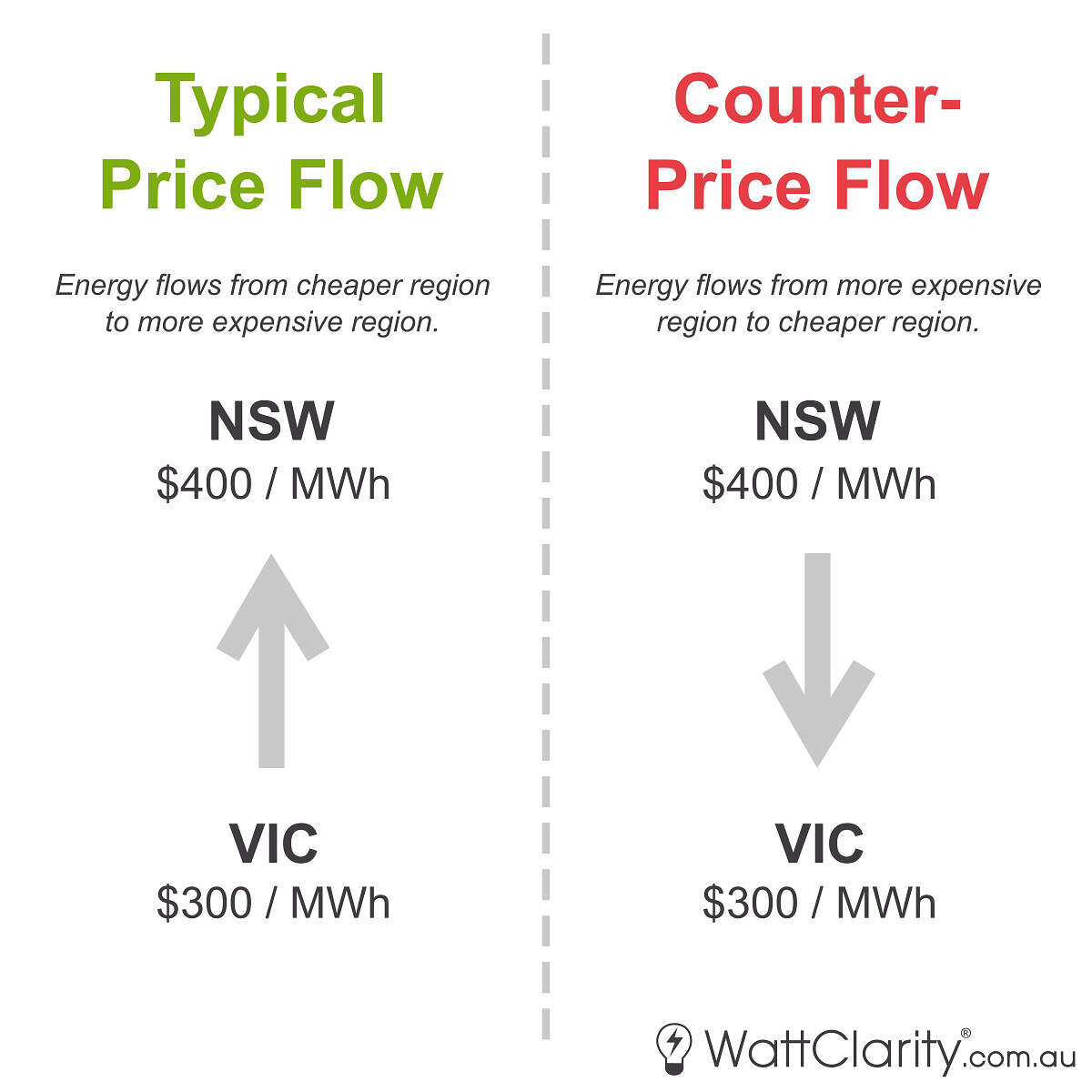

On the left of the image below, we see a typical price flow as just explained above (as the prices are separated, the assumption would be that the interconnector is flowing at a limit).

But then on the right, we see a counter-price flow where electricity is flowing from the more expensive region to the cheaper region.

Left: a typical price flow, where the interconnector is flowing at a limit. Right: a counter price flow.

How and why does that happen?

As explained previously by Paul, and again two days ago by Allan, it’s first important to understand that an interconnector is not a physical piece of electricity infrastructure. It’s instead a mathematical representation of the aggregate electrical flow of all transmission paths between two Regional Reference Nodes (RRNs).

The RRN for NSW is Sydney West and the RRN for VIC is Thomastown – that means that the VIC-NSW interconnector is actually just a representation of the flow of electricity between West Sydney and North Melbourne.

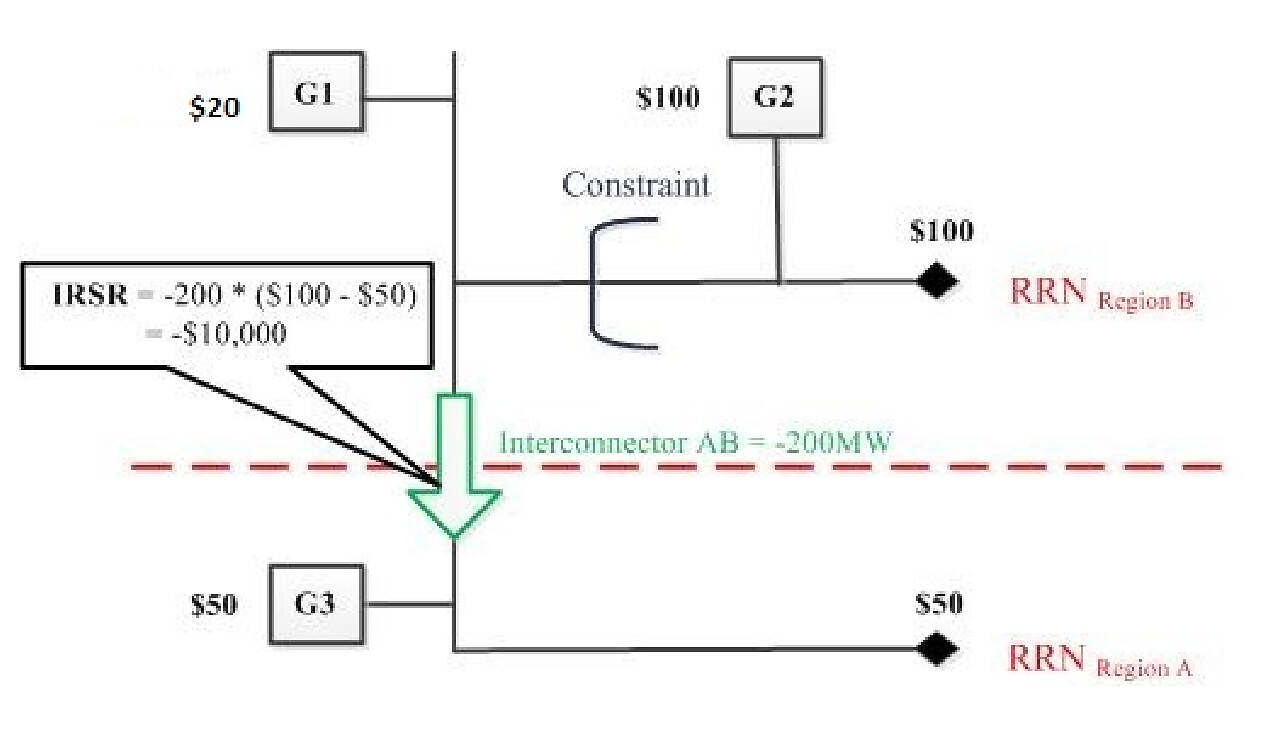

Whilst unintuitive, this ‘zonal pricing’ characteristic of the NEM means that a counter-price flow can still be a sufficient economic outcome, under the market’s ‘least cost dispatch’ design. The image below illustrates how this is possible.

A visual example of how a constraint can lead to a counter-price flow, and hence a negative Inter-Regional Settlement Residue (IRSR).

Source: AEMC

From the example in the image above, we can see how these two market design characteristics allow the NEM Dispatch Engine (NEMDE) to set a counter-price flow:

- Least Cost Dispatch – NEMDE takes as much power as it can from Generator 1 (G1) at $20/MWh. The location of the constraint means that it cannot move it all to the RRN of its own region (Region B) to displace Generator 2 (G2). But NEMDE will take more from G1 to displace Generator 3 (G3) up to the limit of either G1’s availability or southward interconnector capacity. This yields a minimised ‘cost’ of dispatch, valued at offer prices (NEMDE’s objective function)

- Zonal Pricing – the marginal MWh for Region B’s RRN and Region A’s RRN still come from G2 and G3 respectively (G1 is either fully dispatched, or it can’t send more electricity south). So regional prices are set at $100/MWh for Region B and $50/MWh for Region A. This creates the negative IRSR – as explained below – but also creates a satisfactory outcome for G1 as it can bid as low as it likes with no danger of crashing the price it receives.

If the NEM instead had a ‘Nodal Pricing’ design, then Region B would have different prices on either side of the intra-regional constraint:

-

- The price would be $100/MWh for G2 and the location of the RRN (although a nodal market would make needing an RRN redundant).

- The price at G1’s location would be:

- $20/MWh if the interconnector hits its southward limit; or

- $50/MWh if the interconnector was not at limit but G1 was fully dispatched. In this case, effectively Region A includes the part of Region B upstream of the constraint.

In either of those cases a negative IRSR doesn’t occur – so it’s the zonal pricing and not the least-cost dispatch characteristic of the NEM that makes negative IRSRs possible.

Inter-Regional Settlement Residues (IRSRs)

As we’ve seen, generators in the NEM get paid in reference to the price in their own region, and consumers pay based on the same principle.

This seems like a simple and straightforward market characteristic, but it creates at least two issues.

The first issue is the mismatch of pricing for the electricity flowing through an interconnector as we saw in the last example. In that example, this was occurring at a rate of $50/MWh, since Region A consumers were paying $50/MWh, but a portion of their electricity was supplied from a generator receiving $100/MWh.

The second issue is that it becomes difficult for participants to buy/sell electricity from a region other than their own, limiting the pool of potential trading partners – because there is a difference in what they may be paying for electricity, and what their trading partner may be receiving, or vice versa. This is a form of ‘basis risk’.

So to proverbially kill two birds with one stone, a somewhat complicated mechanism, a Settlement Residue Auction (SRA) process has been designed to turn those accumulated interconnector surpluses and deficits (IRSRs) into a financial hedging instrument. This therefore, conceptually at least, provides participants with a product to manage that inter-regional basis risk.

Auto-Clamping

Since the IRSRs become product-ised and auctioned, for several reasons (e.g. counterparty risk, ex-ante design, etc.), larger issues arise if they were to go very negative. As a result, counter-price flows need to be clamped when this begins to happen.

Up until recent years, this hadn’t caused major issues as counter-price flows were relatively rare. But with the NEM experiencing perennial transmission congestion and wave after wave of new solar and wind farms connecting away from demand centers, the management of these flows is becoming more important.

When a run of counter-price flows pushes negative residues towards -$100,000, this clamping process begins. This process was largely manual until the AEMO began automating it, with the latest documentation outlining the automated procedure effective from July 1st, 2021.

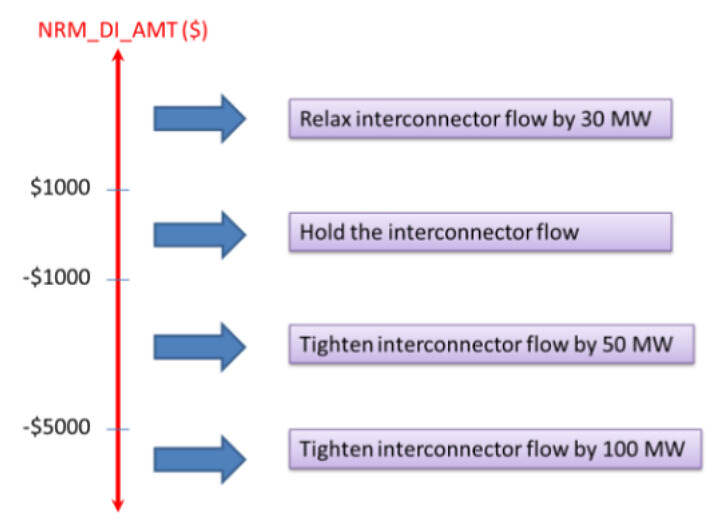

The image below provides an example of how the current automated Negative Residue Management (NRM) process determines how hard to clamp an interconnector’s flow based on different thresholds of negative residues.

An example of the automated NRM process: demonstrating how the interconnector flow is clamped and unclamped based on various triggers, determined by the accumulation of IRSRs in each successive dispatch interval.

Source: AEMO Automation of Negative Residue Management Report

‘Cycling’ is used to describe when this clamping process reoccurs multiple times in a day, and this issue was previously identified by the AEMC in 2014:

The effect of cycling is that it can result in the accrual of increased amounts of negative IRSRs more than once in a trading day. For example, if there are two applications of the clamp within a trading day, then at least $200,000 value of negative IRSRs would have accrued over that day.

These negative IRSRs are paid by the market customers located in the importing region through network (TUOS) charges.

Source: AEMC

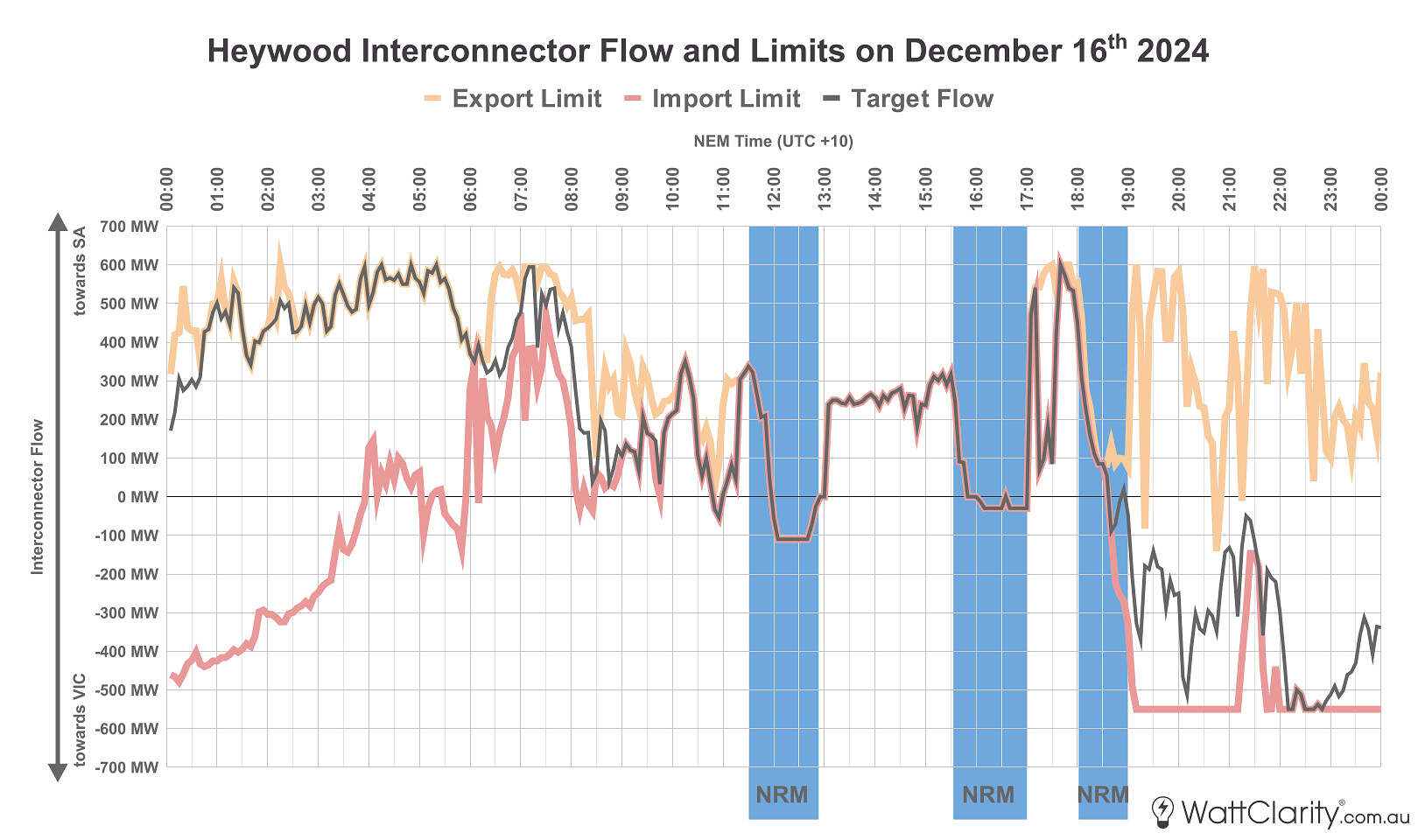

Over the past couple of years, we’ve seen an increasing number of instances of this cycling behaviour. The example below is taken from last month – December 16th, 2024 – and shows one of these NRM constraints cycling through the clamping process three times over eight hours.

Highlighted in blue are the three periods within a single day where the NRM constraint was setting the export limit for Heywood.

Source: ez2view’s Trend Editor and Interconnector Dashboard

I intentionally haven’t shown regional prices in the chart above so we can focus on the interconnector flow and limits, but the series of events are as follows:

- Negative residues accumulated to the point where the NRM constraint needed to clamp flow back towards VIC.

- Shortly after, the negative IRSR fell below the threshold – allowing the NRM constraint to be relaxed in line with the trigger amounts in the automated procedure.

- Only for this to be repeated again, and then again.

This behaviour strongly suggests that the current automated NRM procedure prematurely unclamped flows, twice. The root cause for this is not clear e.g. poor design of the automated unclamping logic, pre-dispatch inaccuracy, etc.

Keep in mind that each time the unclamping then reclamping happened:

- At least $100k of additional negative residues need to be recovered from South Australian customers. This is because when negative IRSRs accrue, they are recouped via the transmission service provider in the importing region.

- An additional 300 to 500 MW of generation needed to be ramped down in VIC, only for it to be ramped back up (with the inverse of those events happening in SA simultaneously).

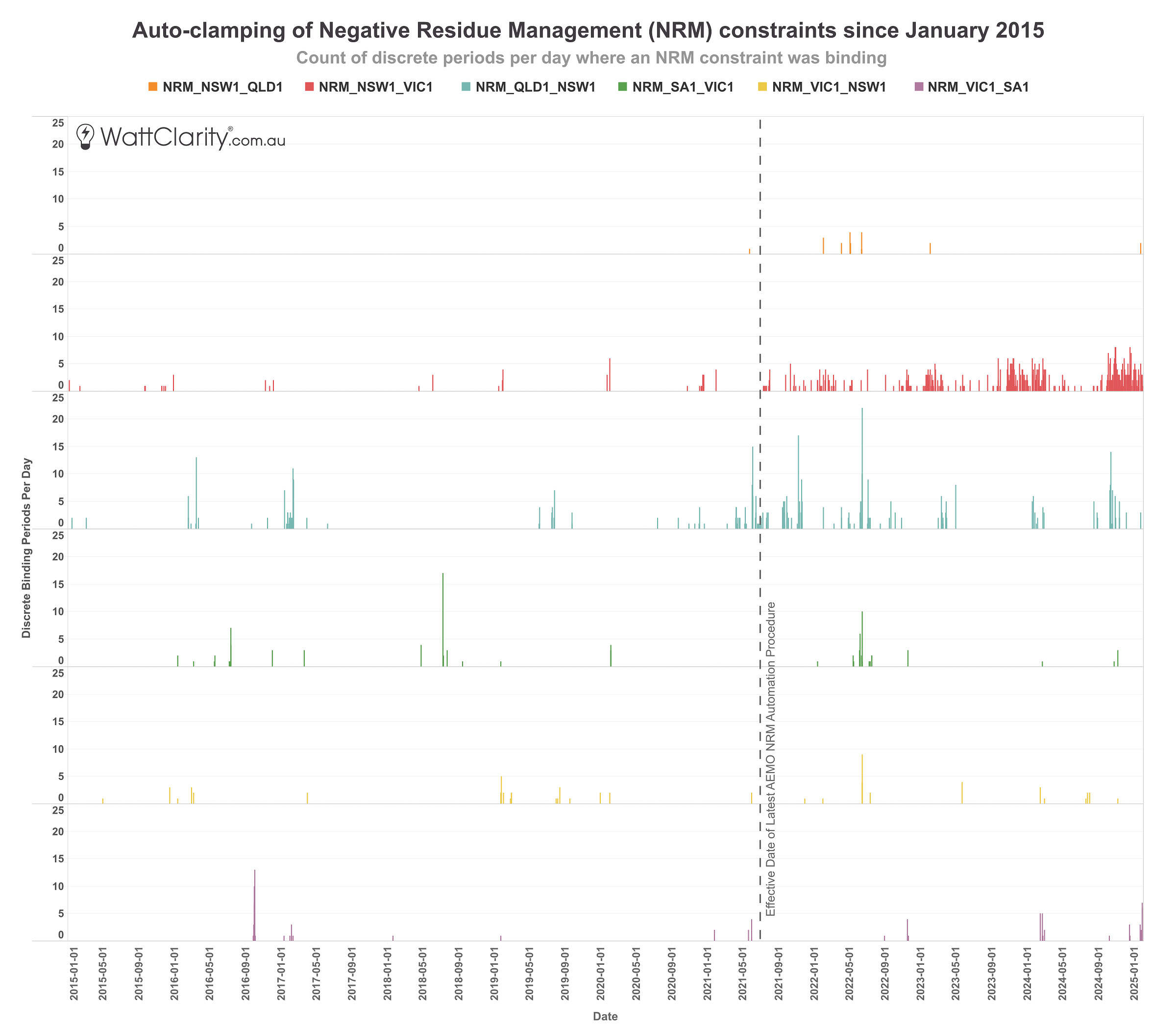

In an attempt to estimate the frequency of this clamping, below I’ve created a chart showing the count of non-continuous dispatch intervals with a bound NRM constraint.

We’ve seen an increase in the number of discrete instances where NRM constraints have begun binding.

Source: AEMO MMS

Whilst the previous Heywood example showed an NRM constraint actually impacting flow by setting the export limit, this chart simply shows the count of unqiue instances that the automated clamping procedure made an NRM constraint have a marginal cost in NEMDE’s dispatch solution.

We can see clear seasonal trends, with these constraints binding for more periods in spring and summer (where solar and wind production is generally higher). More notably, we see that the NRM_NSW1_VIC1 constraint bound almost every day (and commonly multiple times each day) throughout 2024.

Whilst other underlying market dynamics are surely at play, there appears to be a coincident timing of the increase of these occurrences and the effective date of the current set of automated NRM procedures.

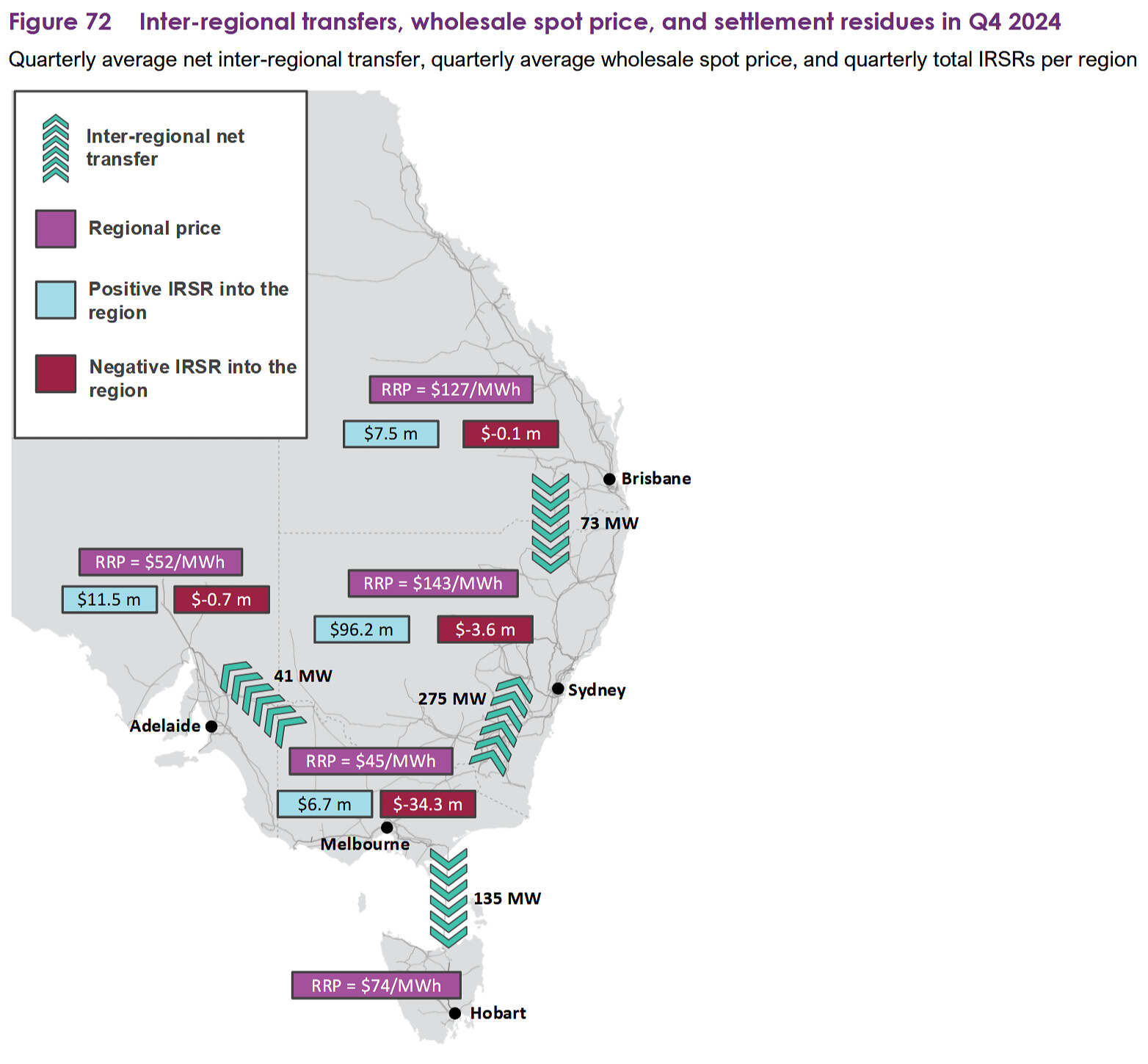

As for the overall cost to consumers of these negative residues – the figure below has been taken from the AEMO’s Quarterly Energy Dynamics (QED) report for Q4 2024, released earlier today, and shows that negative IRSRs in Victoria were -$34.3m for last quarter alone.

Negative IRSRs in Victoria were -$34.3m last quarter, the equivalent of approximately -$372k per day.

Source: AEMO QED

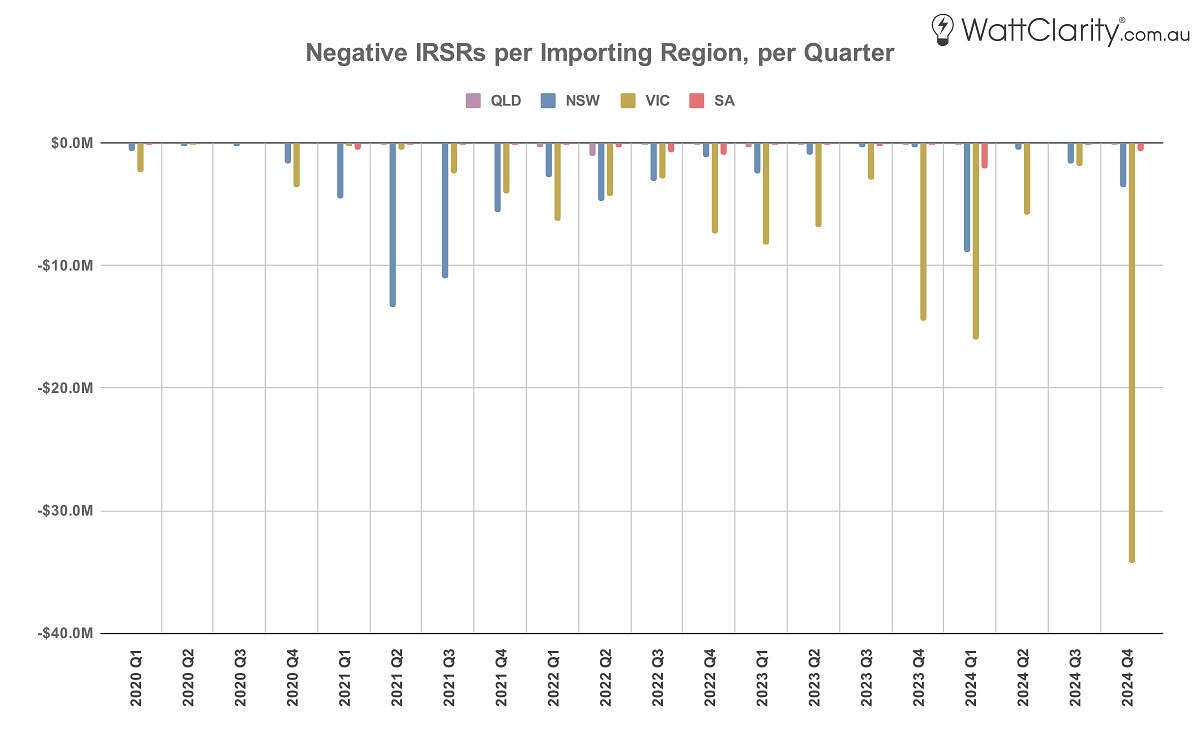

And now below we can see the five-year trend of these negative IRSRs.

Most notably in Victoria, negative residues have been getting more extreme.

Source: AEMO QED

Key Takeaways

The NEM’s zonal pricing design and IRSR arrangements have already been tested by the influx of new solar and wind generation to the outer reaches of southern mainland regions in recent years.

This effect where clamping has cycled multiple times in a day is the result of an automated process – and perhaps one that still needs to be refined. The AEMO’s NRM automation documentation referenced earlier (and here again) states that the step sizes for clamping and the residue triggers will “be continually reviewed on a half-yearly basis in order to improve the NRM process” but it appears that material changes have not been made since they were made effective in July 2021.

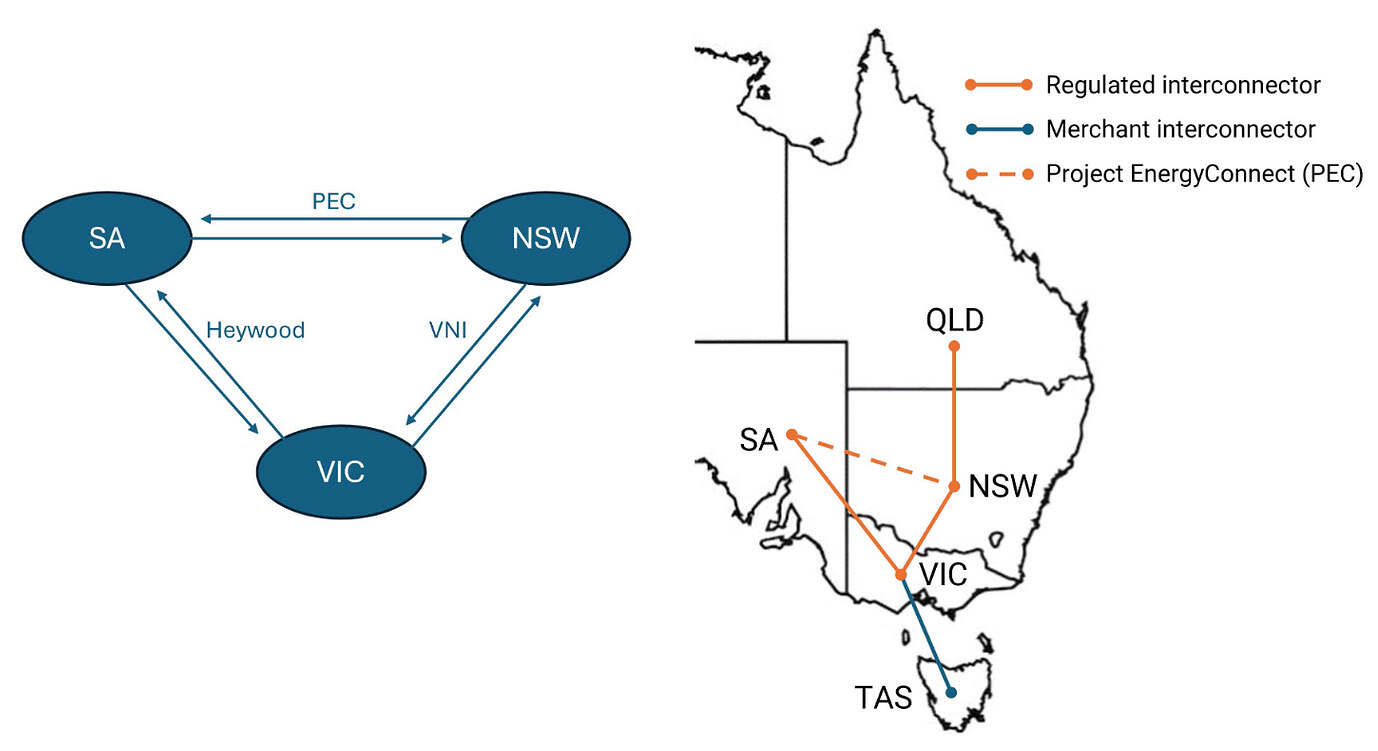

The introduction of PEC will make the management of negative IRSRs even more complicated – as loop flows will be able to occur once Stage 2 of the project enters the market in 2027.

PEC will create the first interconnector transmission loop in the NEM, and the AEMC suggests this is likely to cause more frequent negative IRSRs.

Source: AEMC

The AEMC are currently seeking input on how the existing IRSR arrangements will apply for PEC. Submissions for the consultation close today the 30th of January 2025, with a final determination expected from the AEMC on the 27th of March 2025.

Leave a comment