This article was originally published on LinkedIn. Reproduced here with permission.

Disclaimer: This is my personal opinion and bears no representation of my employer.

The AEMC recently published a draft paper on the Transmission Planning and Investment Review (TPIR).

I thought it was notable for suggestion three options crafted to sidestep or short circuit the Regulated Investment Test for Transmission (RIT-T).

To me this demonstrates an admission that the RIT-T does not work.

At the start of the TPIR the AEMC questioned whether an alternative economic model should be assessed before immediately ruling this option out. Specifically – a “consumer benefits test”, which measures the net benefits to consumers. Why would they rule that out, isn’t that exactly what we want? Currently we use a “market benefits test”, which typically grossly underestimates the value of transmission to consumers. This measures total system costs, rather than the bills of consumers.

At the root of this is the saying “in the long run, price converges to the cost of the system”. This would imply that a model measuring the total system costs can find the best solution for consumers because they are equivalent.

This is a myth, although a pervasive one. Let’s explore by looking at some other example markets.

Firstly, let’s think about wheat:

- Storage is relatively cheap. This allows producers to smooth out the differences between price and cost.

- Traded and transported internationally. More competition, as well as smoothing out gluts and deficits.

- The cost of land (major input) is proportional to productivity. This means rates of return are neither extremely high nor low.

- Land lasts more or less indefinitely.

- Land can be used for other substitute production, e.g. barley, or sheep grazing. This means low wheat prices discourages wheat production at the next sowing.

When we look at these characteristics, we should expect that the saying “with time, price = cost” is somewhat true. If costs and prices are too mismatched changes in supply, storage, and demand will relatively quickly act to rebalance them, i.e. within a few seasons or years.

The permanence of land and its revaluation depending on productivity means there are few opportunities to unlock unique resources with much lower production costs. There are also no price shocks related to land capital costs, although clearly there are shocks from input costs, weather and war.

Now let’s consider gold:

- Storage is relatively cheap. This allows producers to smooth out the differences between price and cost.

- Traded and transported internationally. More competition, as well as smoothing out local gluts and deficits.

- Ore deposits deplete with extraction.

- New deposits tend to become more difficult to extract, counteracted by improvements in technology.

- Uneconomic producers do not quickly retire, but mothball, or stockpile until prices are high.

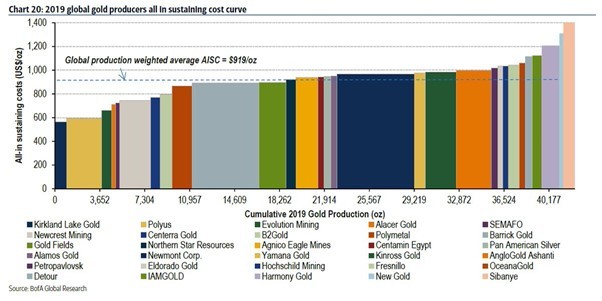

The major difference between the examples is that a productive mine does not necessarily cost more. This leads to a cost curve where producers have unique circumstances and there is a divergence between the traded price and the cost of active producers.

Over time the low cost mines will deplete themselves more continuously as they are always profitable. This removes them from the cost curve and price is set at a higher level. New entrants could be anywhere on the curve but are more likely to be at the higher end.

We could say that “in the long run, prices tend towards the marginal cost”, but clearly there is an enormous producer surplus over that time. The sum of price over time is much greater than the sum of costs.

For example, Cadia gold mine in NSW reports that their costs are about half the gold price. For a mine life of 50 years this represents an incredible producer surplus over time. It would be nonsensical to presume that these profits somehow even out in the long run for gold consumers. We can find other examples too, e.g. if Cadia’s production costs increased by a tenth without changing their total production it would have zero effect on gold prices – now, or in the long run.

Now let’s reflect on these commodity examples with the NEM:

- Storage is relatively expensive compared to the typical cost or price of production. Surfeit and deficit are not easily balanced over the short, medium, or long term.

- International trade is zero, and interstate trade is poor. Competition is localised. Gluts become a major risk for producers. Shortfalls become a major risk to consumers.

- Economic life of assets is uncertain, but long. In between the two examples for certainty and longevity.

- Uneconomic producers do not retire until operating costs exceed revenues, or if major capital refurbishment is unviable.

Comparing NEM electricity to the other examples we see it shares more with gold than with wheat. That is, there are more reasons why price does not converge to cost in the long run. If anything, we see that price should sit in a range between a price high enough to encourage new entrants, and a price low enough to bring the least economic plant to its demise.

Price could be sustained within this range for a very long time absent any other changes. This means an individual generator has no guarantee they will recoup their capital, and at the same time as some generators are making write-downs, others are enjoying profits higher than they anticipated. Unlike wheat with a short investment cycle and substitutability, generators are stuck with whatever macroeconomic changes are thrust upon them. The anticipation of future profits is no guarantee of them, and there is no relationship balancing write-downs with super profits.

This is at odds with the RIT-T which presumes that all generators get a guaranteed return on assets, plus their operating costs covered. Running least cost models in this manner produces bizarre generator combinations that don’t make sense, e.g. lots of cheap solar which reduces system cost, but where in reality none of the solar farms will make any money because the price is $0 all day. I remember seeing combined cycle gas being assumed to be built in some old RIT-Ts which was immediately jarring for someone in generation who knew that new CCGTs were totally uneconomic and therefore there were none in development.

Compared with gold, electricity has less uniqueness amongst assets. A good wind farm is not twice as productive as a typical wind farm. However, there is a locational uniqueness that gives value to diversified resources up to a point. Often cost based (RIT-T) modelling assumes that any amount of a resource can be built in any region and that it is completely homogenous in cost and value. The ISP measures locational resource better, and resource adequacy is a decent proxy for value, but it is still better to measure price outcomes.

Like gold, spare capacity in electricity supply can be quickly used up in a supply/demand shock. One of the most important shortcomings of cost-based modelling is the fact that there are no price shocks. Quite weird considering we have an energy-only market, and we fully expect price to sometimes be a hundred times higher than the marginal cost.

This is related to a more fundamental problem in that cost-based modelling calculates the wrong volume. So even if you modelled a fuel price shock in a cost-based model, you would only measure the change in cost for the units affected by the fuel price. This underestimates the cost to consumers because the units with a fuel price are most likely to be setting price across all generation, not just their own. E.g. 25 GW at $500, not 1 GW at $500.

One criticism of price-based modelling is that it is more complicated and thus less precise. This carries some truth – there is more variance in the results depending on the changes to assumptions. However, this is more than made up for in accuracy because we are actually measuring the quantity of interest. Let’s not forget that all new entrant generators rely on price-based modelling to reach financial close, and certainly the majority of that new generation is underwritten by contracts with buyers (corporate, retailer, or government) who also rely on price-based modelling to evaluate offers made to them. There is consensus amongst major buyers and all producers that price-based modelling is more suitable despite the knowledge that it is subject to greater sensitivity to assumptions. It strikes me as bizarre that only the governing bodies choose to use cost-based modelling and are too invested into the economic mythology to actually observe the goings on of the market. [TNSPs don’t choose cost-based models, they are forced]

It would be nice to actually use some empirical economics. We have an absolute wealth of historical data which could be used to give reasonable assessments of the value of transmission projects – both individually but also in aggregate. Comparing historical data to the synthetic model of future expectations helps to refine a better model. We can also measure ex-post the impact of a project to check whether customers are getting a good deal. Both cases would inform and improve our modelling for future transmission projects. Using historical data and allowing modelled transmission to alter the dispatch price through the bid stack is how I became convinced transmission is fabulous value for money for consumers.

The only way to reduce wholesale prices for consumers is to change the price setter from a higher price to a lower price. The more that renewables set price the more detached from international fossil fuel prices we become.

Coming back to the TPIR.

The first option is to help make early works easier – pretty uncontroversial.

The other two options seek to remove the cost-benefit analysis from the process.

Oh well that settles it! We won’t be needing cost-based modelling because it’s simply too late for cost-benefit analysis.

In the last 5 years we missed the opportunity to save consumers billions of dollars in wholesale energy, and now (unluckily) we have higher capital costs for all the new infrastructure that we could already be benefiting from.

Governments are taking the reins because nothing is being delivered and AEMO is saying that the lights might go out if we don’t get on with it. Thankfully consumers will be somewhat protected from inflation of the construction costs by taxpayers.

What the hell has been the point of the grand reform agenda over the past 4 years? What value did it create for all the person-hours thrown at it?

Thanks for coming to my TED talk.

About our Guest Author

|

Tom Geiser is a Senior Market Manager at Neoen and is currently based in Sydney.

You can find Tom on LinkedIn here. |

Be the first to comment on "Cost-based Modelling is Doing Consumers a Disservice."