This is the third instalment in a series examining the Capacity Investment Scheme (CIS) and its track record to date. In Part 1, we noted that the majority of projects from earlier tenders don’t appear to have yet progressed through to financial close or construction. In Part 2, we explored some of the reasons why.

Here in Part 3, I turn to an important dimension of risk relevant to CIS projects — curtailment.

Does the CIS cover network curtailment risk?

A recurring side-debate about the CIS has been whether the scheme underwrites curtailment risk. This debate has played out most visibly online, with Ben Beattie originally arguing that yes, the government was underwriting curtailment, while Simon Holmes à Court and others responded by saying no, curtailment risk was not in fact covered by the scheme. Broadly speaking, the consensus from both sides appeared to be that curtailment risk should not be covered, as this would leave the Commonwealth exposed to open-ended risk.

Without wanting to get involved in that specific debate, we were curious to know more, so back in July I asked our WattClarity readers whether anyone could shed light on the question “to what extent does the CIS cover curtailment risk?”.

CIS Agreements (CISAs) are dense legal documents with lots of legal jargon, so in that article I walked through the revenue floor underwriting mechanism and compared clauses in the pro-forma for Tender #1 vs Tender #4.

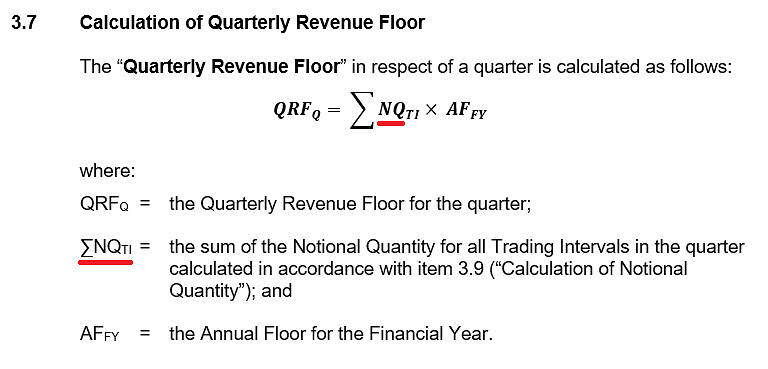

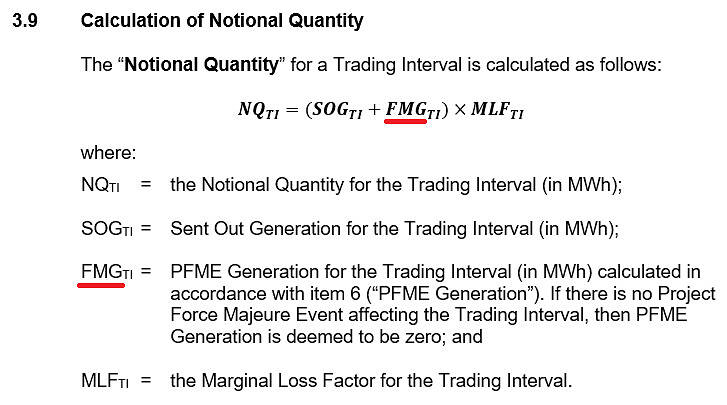

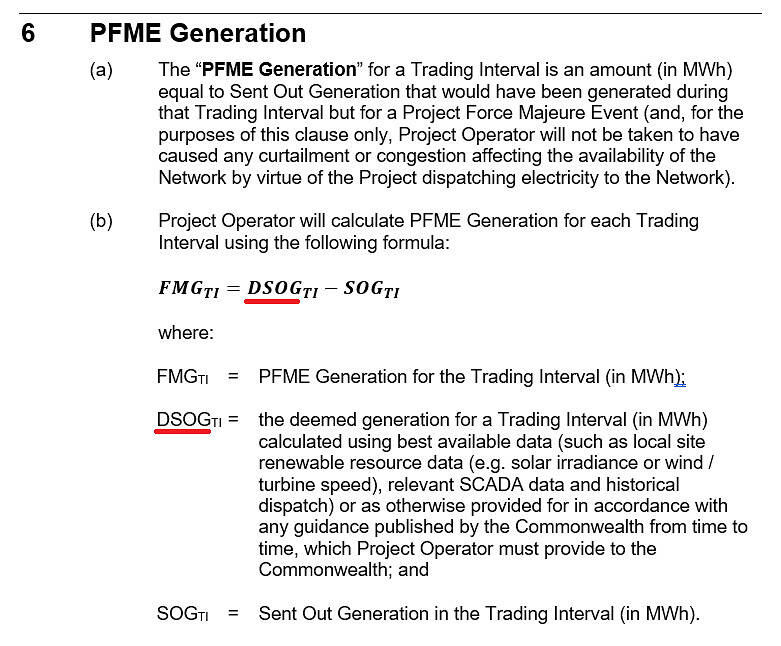

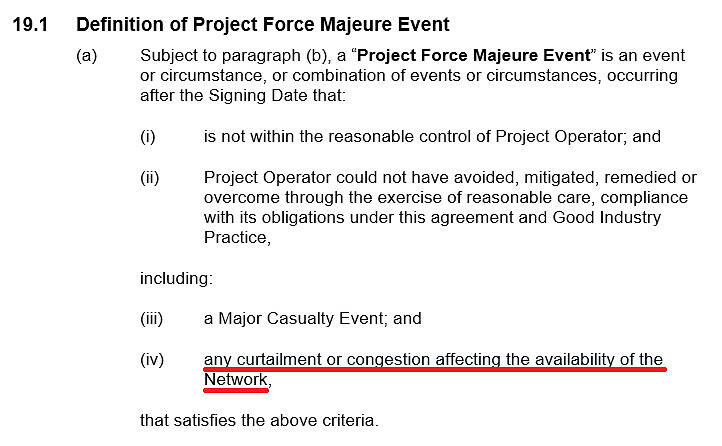

The key clauses were Schedule 1 Section 6 and Section 19.1, which appeared to treat network curtailment as a component of “Project Force Majeure Event (PFME) Generation”, which in turn was included within the notional quantity calculation that ultimately helps to determine the revenue floor top-up amount. For simplicity only, from here on in I’ll refer to those clauses as they relate to the revenue floor notional quantity as the “curtailment provision”.

|

|

|

|

The calculations and clauses that determined the notional quantity for the revenue top-up payment in the draft pro-forma CISA for Tender #1.

Source: ASL

It later turned out that the pro-forma document I was actually looking at was not the final CISA for Tender #1, but instead a draft CISA for Tender #1. Since I wrote that article, the scheme’s administrators — The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW) — have since clarified that PFME Generation was excluded as a component of the notional quantity calculation in the final release of the Tender #1 CISA pro-forma.

Approximately one month after I published that article, in their August 2025 newsletter, DCCEEW made the following statement:

In June 2024, we conducted early consultation on the draft Generation Capacity Investment Scheme Agreement (CISA) for Tender 1 in the National Electricity Market (NEM).

The draft CISA included a clause that stated that the volume of generation used to calculate support payments includes deemed generation during a force majeure event.

Deemed generation is generation that does not occur but would have occurred, had the force majeure event not eventuated.

The referred clause in the consultation Draft Proforma Tender 1 CISA was changed following the consultation process. No generation CISAs have been, or will be, executed that include that clause.

No generation CISAs have been, or will be, executed that provide revenue underwriting for curtailment.

You can visit CIS Tender 4, Stage B for the most recent NEM Generation CISA pro forma

So that statement from the federal government appears to put to rest one part of the debate: no executed CISA underwrites network curtailment risk.

So, end of discussion?

While that debate might be settled, an interesting wrinkle appears lost. On the ASL website, the final CISA pro-forma for Tender #1 has a publication date of August 27th 2024.

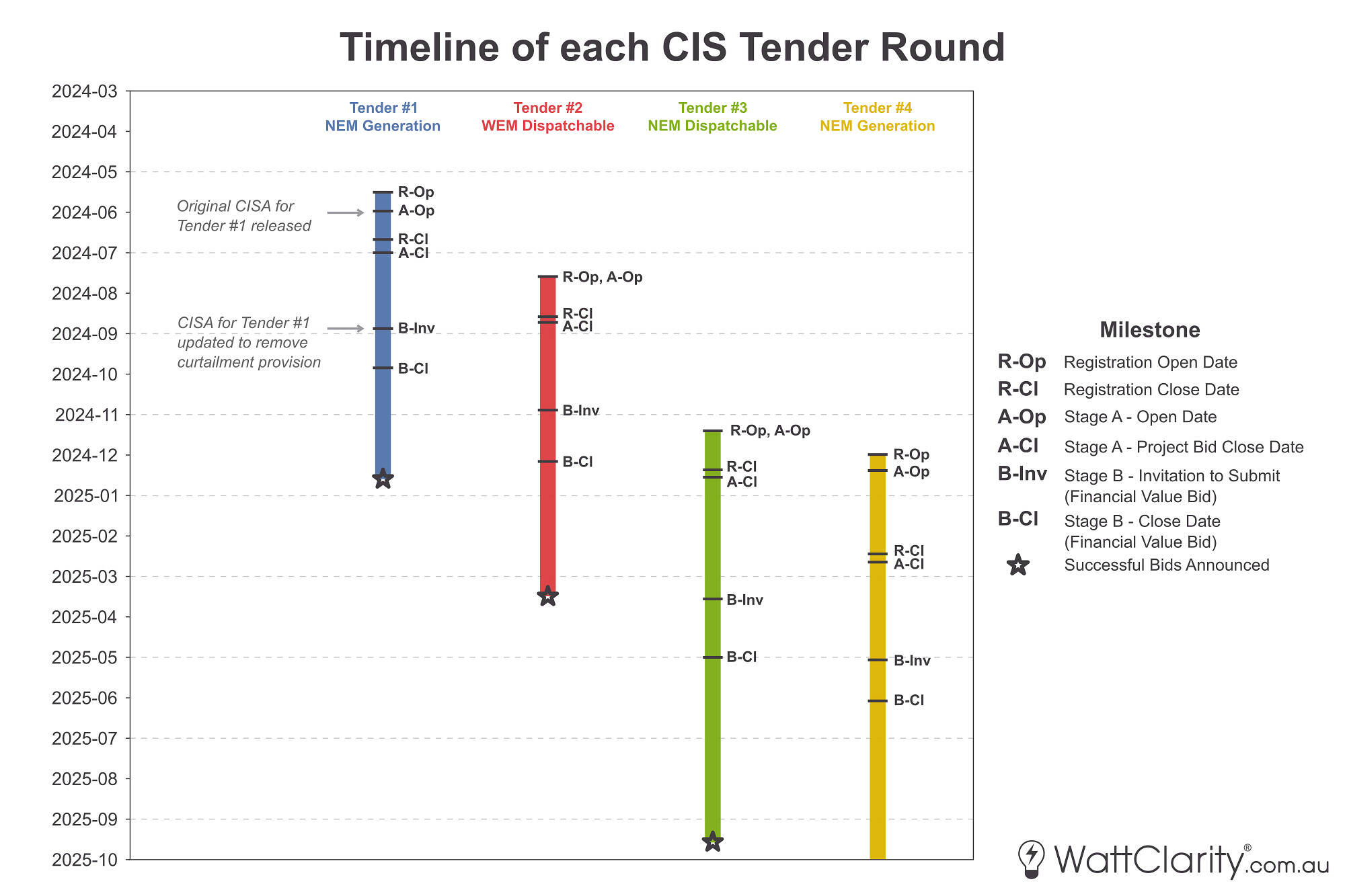

If we place that on a timeline, the removal of the curtailment provision occurred after Stage A applications had been submitted, and just as projects were invited to bid their revenue floors. In the graphic below, I’ve charted the publication date of the change alongside the Tender #1 process and subsequent tenders in order to visualise when the change occurred.

The timing of when the curtailment provision was removed from the CISA raises a few natural questions about its impact on the bidding process. 52 projects were invited to bid in Stage B of Tender #1.

Note: By ‘updated to remove curtailment provision’, we are referring to the exclusion of PFME Generation as a component of the notional quantity calculation, as has been clarified by DCCEEW.

Source: ASL, DCCEEW

This raises a few questions:

- Was every single bidder fully aware of the change?

- How was it communicated to participants?

- Did anyone else — as I initially did — mistakenly view the draft CISA for Tender #1 thinking it was the final version when preparing to bid in Stage B (or even in later tenders)?

- Was the clause update (or even its existence in the first place) acknowledged by the broader industry at the time, or did it go largely unnoticed until discussion resurfaced one year later?

- For projects shortlisted for Stage B, did they adjust how they were going to bid after the change was made?

Without implying fault, these are natural questions given the significance of curtailment risk in project economics and hence formulation for a revenue floor bid.

Forecasting curtailment: an exercise very open to interpretation

If all developers in the tender round were aware of the change, it likely required them to very quickly reassess congestion and curtailment risks and to decide how — and whether — to adjust their revenue floor bids.

Forecasting curtailment is far from straightforward. Industry-standard tools such as PSSE or PLEXOS are widely used for these assessments, but their outputs are highly sensitive to the assumptions and data fed into them.

Looking at known areas of congestion

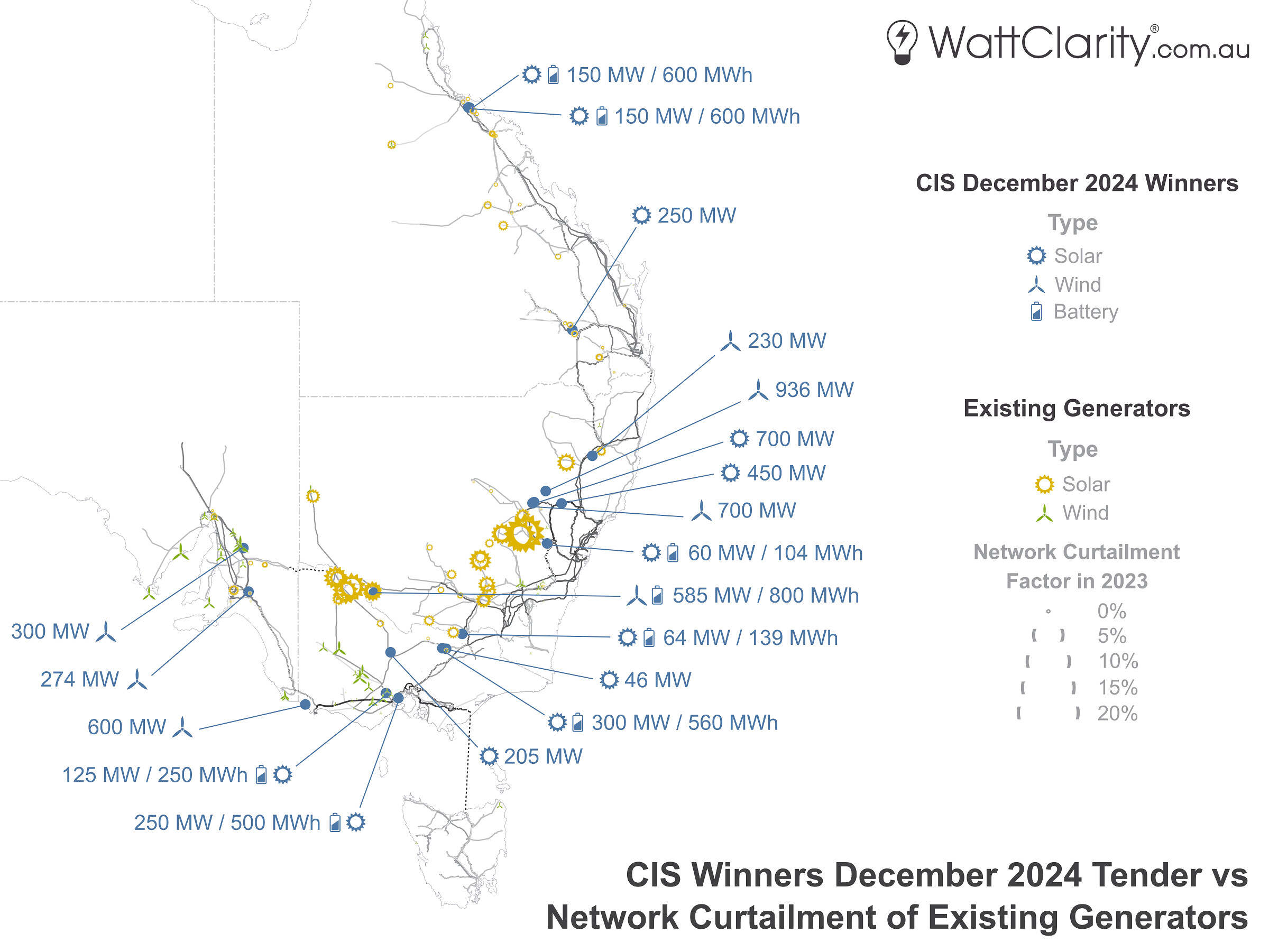

Conveniently, in December of last year, a WattClarity reader asked me to plot the Tender #1 winners on a map against known areas of network congestion in the NEM. For reference, the map of projects versus network curtailment is shown below.

At first glance, only a subset of winning projects appear to be located in areas with visible network curtailment.

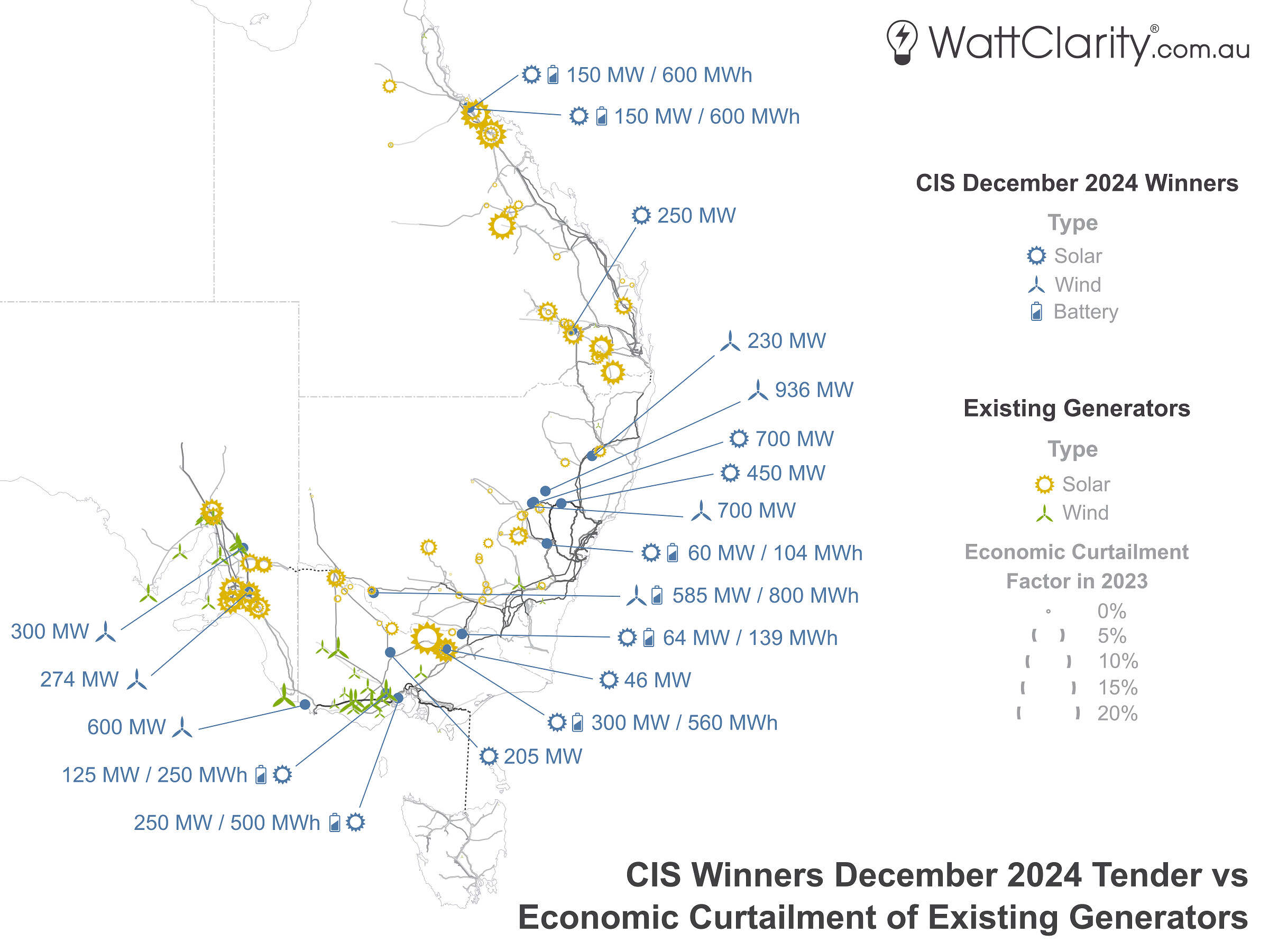

However, when we compare the same projects against areas of economic curtailment, a different picture emerges.

But why does economic curtailment have anything to do with this?

Many people in the industry have a habit of talking about network curtailment and economic curtailment as though they are completely separate concepts, but in practice they overlap.

Allan O’Neil explained this well in this WattClarity article, using the term forced curtailment for situations where the network physically limits output, and economic offloading for cases where a generator voluntarily reduces output through its bidding.

The key point is that they shouldn’t be seen as entirely distinct from each other. In the physical market, units can often bid low to avoid network constraints, which can suppress spot prices, which in turn may trigger economic curtailment. Conversely, economic curtailment can hide the full extent of network congestion that would have otherwise occurred.

Curtailment patterns are unlikely to remain static. Intra-regional power flows (relevant to network curtailment) and inter-regional power flows (relevant to economic curtailment) will almost certainly evolve in unexpected ways — particularly as coal-fired power stations located on the backbone of the grid retire. This means that today’s curtailment maps and modelling can only ever provide a temporary and uncertain guide to future risks.

Key Takeaway

In Part 1 of this series, we saw that AEMO’s generation information data suggests very few of the 19 projects awarded in Tender #1 have progressed to ‘committed’ phase — nearly 10 months after the award date. In Part 2 of this series, we examined how some externalities, like rising construction costs and other development hurdles may be contributing to delays, but more importantly, we summarised industry concerns that some of the revenue floor bids in early tenders may have been pitched at levels so low that projects are now unable to progress to financial close — a situation driven in part by fierce competition in the heavily over-subscribed tender rounds and the absence of viable alternatives outside the CIS.

Here in Part 3, we’ve seen that the federal government have staunchly expressed that curtailment risk is not underwritten by the CIS — although the wording of clauses in an earlier draft documents suggest that it was originally proposed to bidders that it could be. The subsequent updating of the curtailment provision (i.e. changing the component of the notional quantity calculation for the payout amount) partway through Tender #1 adds yet another layer of uncertainty about how revenue floor bids may have been priced.

In the next and final part of this series, I’ll turn to the Nelson Review and attempt to read between the lines to highlight lessons that are most relevant to the design and implementation of the CIS so far.

Leave a comment