In recent months, discussion around the Capacity Investment Scheme (CIS) has shifted from broad commentary to a sharper focus on outcomes so far.

In this series of articles, I’ll step through a few of the discussion topics that have been front and centre — the recent tender results, delays in projects reaching financial close, debates about curtailment risk, questions about how the CIS ties into the AEMO’s planning outlook, and the intersection with issues being raised in the ongoing Nelson Review– with a view to exploring what these threads collectively suggest about the scheme’s success to date.

This series will be broken into four parts which I’ll aim to publish progressively over the next couple of weeks:

- Part 1: Tracking the progress of CIS projects post-award.

- Part 2: Understanding why there are delivery challenges.

- Part 3: The treatment of curtailment risk.

- Part 4: Policy lessons highlighted by the Nelson Review.

How the CIS has evolved since first announcement

When first announced in December 2022, the CIS was framed as a mechanism to support investment in dispatchable technologies (such as battery storage), ahead of the anticipated retirement of coal-fired power stations over the coming decade.

In November 2023, the Federal Government shifted the scope of the scheme to include Variable Renewable Energy (VRE) projects, such as solar and wind. This adjustment was partly done to create a policy replacement for the Renewable Energy Target, which is due to expire in 2030. At that stage, the government set a capacity target for the scheme of 32 GW: consisting of 23 GW of new generation and 9 GW of new dispatchable capacity.

In July 2025, this target was raised, with the government now aiming to deliver 40 GW of projects by 2030 — with the target comprising 26 GW of new generation and 14 GW of new dispatchable capacity.

Recapping the tender rounds thus far

Projects that are awarded contracts under the scheme receive revenue collars: this cushions downside risk if/when electricity market conditions are unfavourable, while requiring projects to share excess returns with government if/when conditions are favourable. To apply for a contract, proponents must bid each of these collar parameters (i.e. a revenue floor and ceiling). The intention of the bidding process is to limit the commonwealth’s exposure to market risk by favouring projects that require the least amount of government underwriting.

Since its launch, two pilot rounds and three full tenders have been completed. Tender #4 is currently underway, with results expected next month.

| Tender Round | Type | Target | Regions | Registrations | Successful Bids | Outcome Announcement |

| Pilot Tender #1* | Dispatchable | 0.9 GW | NEM – NSW | Not Announced. | 4 Projects

1.1 GW / 3 GWh |

November 2023 |

| Pilot Tender #2 | Dispatchable | 2.4 GWh | NEM – VIC & SA | 155 Projects

33 GW / 90 GWh |

6 Projects

1 GW / 3.6 GWh |

September 2024 |

| Tender #1 | Generation | 6 GW | NEM | 119 Projects

41 GW |

19 Projects

6.4 GW |

December 2024 |

| Tender #2 | Dispatchable | 0.5 GW / 2 GWh | WEM | 22 Projects

3 GW / 19.6 GWh |

4 Projects

0.7 GW / 2.6 GWh |

March 2025 |

| Tender #3 | Dispatchable | 4GW / 16 GWh | NEM | 166 Projects

44.5 GW / 176 GWh |

16 Projects

4.1 GW / 15.4 GWh |

September 2025 |

| Tender #4 | Generation | 6 GW | NEM | 106 Projects

35.7 GW |

TBA | Expected October 2025 |

| Tender #5 | Generation | 1.6 GW | WEM | TBA | TBA | Expected March 2026 |

| Tender #6 | Dispatchable | 2.4 GWh | WEM | TBA | TBA | Expected March 2026 |

| Tender #7 | Generation | TBA | NEM | TBA | TBA | Expected mid 2026 |

| Tender #8 | Dispatchable | TBA | NEM | TBA | TBA | Expected mid 2026 |

Note: The CIS Pilot Tender #1 was also part of the NSW Roadmap Tender Round #2 (a.k.a. the LTESA scheme). The round did not have a GWh target, and the number of projects registered for this round was not publicly disclosed.

Source: DCCEEW, ASL

Tracking the progress of CIS projects post-award

Tracking the progress of any development project in the NEM is not straightforward. One of the few public sources available is the AEMO’s Generation Information dataset, which classifies development projects into three broad categories based on five key criteria (land, contracts, planning, finance, and construction). Committed projects have satisfied all five criteria and are considered highly likely to proceed. Anticipated projects meet at least three of the criteria, but if the developer fails to provide new information to the AEMO about their project within a six month period they are downgraded to “proposed” status or removed. Proposed projects are simply projects that have been announced by a company but satisfy less than three of the five criteria, these projects vary significantly in their likelihood of actually being built.

While this framework provides a useful shorthand for tracking the development pipeline, the dataset is published at an irregular cadence and has been known to have many shortcomings (as I’ve previously written about), so it should not always be treated as a reliable guide. That is in spite of the fact that it is the only centrally-managed dataset for development projects in the NEM, and plays an important role in the AEMO’s Electricity Statement of Opportunities (ESOO) modelling.

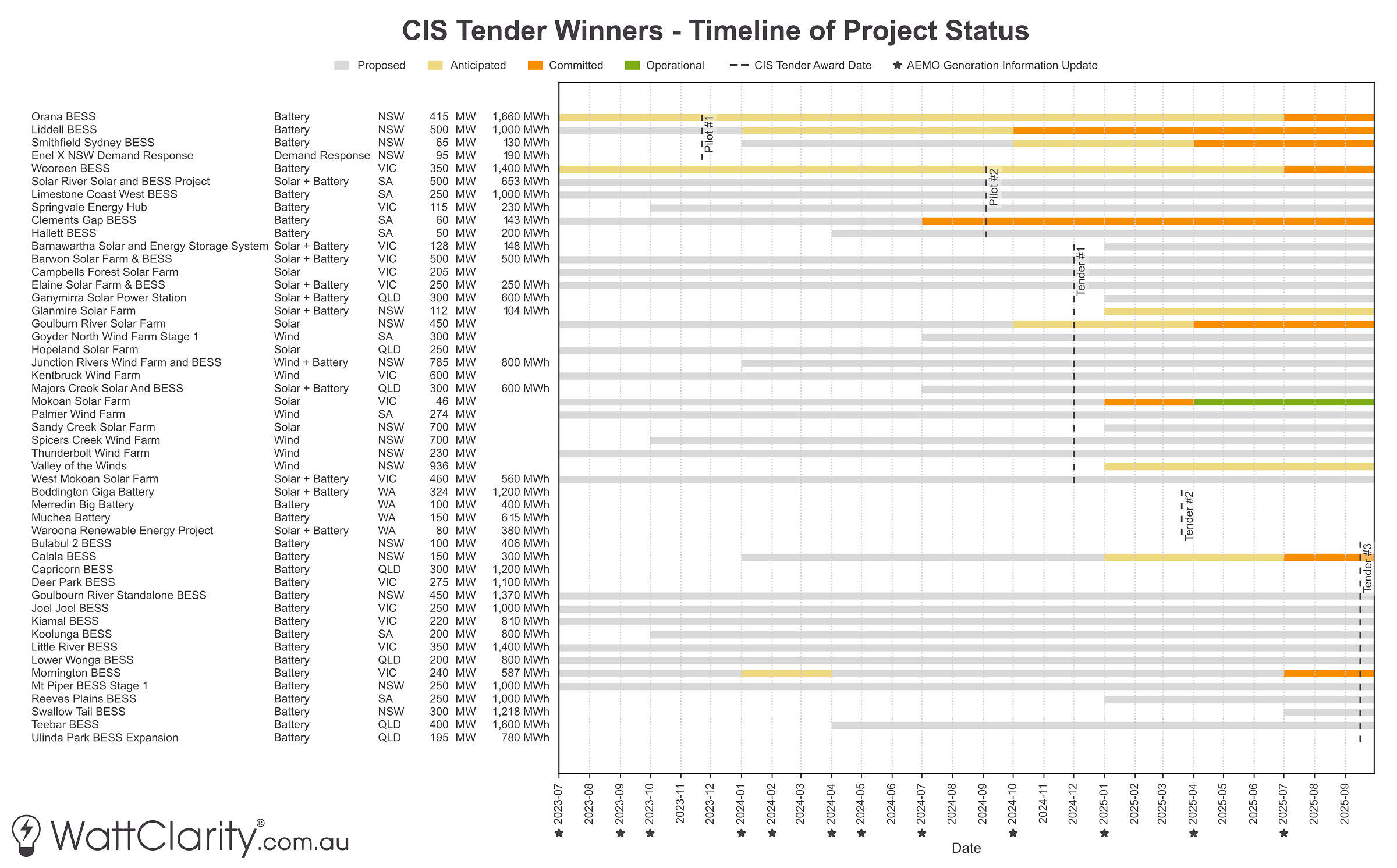

In the Gantt chart below, I have scraped and compared multiple archived versions of the AEMO’s Generation Information spreadsheet to cross-check project status before and after CIS awards.

Many CIS-awarded projects appear to have been slow to progress to ‘committed’ stage, with the majority of the projects from earlier tenders still marked as ‘proposed’ in the latest AEMO Generation Information data.

Source: DCCEEW, AEMO

What the chart shows is that even after contracts have been awarded, many projects remain slow to move through AEMO’s status categories — underlining the challenges of translating tender success into financial close or the commencement of construction.

Using Pilot Tender #2 (awarded in September 2024) and Tender #1 (awarded in December 2024) as examples, the majority of these projects remain marked as ‘Proposed’ in AEMO’s latest reporting, even though up to a year has passed since being awarded a contract.

What does this mean for capacity planning?

Last week, Paul examined the recently released ESOO 2025 through a few different lenses. His article highlighted how the modelled reliability outcomes can vary significantly depending on whether the analysis includes only ‘Committed’ projects, or optimistically includes ‘Anticipated’ and other blue sky projects.

Paul’s article, in addition to recent comments by Oliver Nunn that suggested that the AEMO’s Integrated System Plan (ISP) is “divorced from reality” — underscores the risk of the industry treating CIS capacity as a straightforward, bankable solution to system adequacy. While the scheme may secure gigawatts on paper, actual reliability depends on gigawatts in the system — including factors such as timing, ramping, firming, and essential system services that sit outside the scheme’s design.

Key Takeaway

Tracking project progress post CIS-award is difficult. The AEMO Generation Information dataset, while central to market modelling, is inconsistent and published irregularly. Even so, it suggests that many CIS-awarded projects have been slow to progress through the pipeline, with a large share still marked as ‘Proposed’ up to twelve months after securing a CIS contract.

In Part 2, we’ll dissect potential reasons why there have been delays, and summarise some of the recent industry commentary surrounding success of the scheme thus far.

Leave a comment