Last week I published the article Four questions we’re pondering ahead of the 2025 Clean Energy Summit in Sydney, which served as our preview of some NEM-specific themes ahead of the annual event.

With the conference concluding on Wednesday, this article today serves as our review, summarising some of the ‘answers’ — or rather, the responses we interpreted — to the four original questions we were pondering.

How far has the clean energy compass swung?

Only gradually, for now.

In my article last week, I noted the many impending changes at the Clean Energy Council (CEC), including the departure of long-serving CEO Kane Thornton, and the organisation’s shift to acknowledge the role of gas in the short to medium term. There was a clear sense of transition at the summit, and at times it felt like a swan song for the outgoing leadership team.

However, unsurprisingly, there were no sweeping announcements about the CEC’s future, and the role of gas received little attention during the opening panel featuring three CEC board members, who instead focused on community engagement, investment challenges, and workforce needs.

By contrast, AEMO CEO Daniel Westerman was far more clear about the ongoing importance of gas in maintaining system reliability, using the ‘g-word’ nine times during his keynote. That speech, now published on the AEMO’s website, offers a striking contrast to his headline-making “100% instantaneous renewables NEM-wide by 2025” ambition from four years ago.

But the opening speech that grabbed the most headlines was Ross Garnaut’s address, which warned “the energy transition is sick”. He argued that current policy settings are falling short of what’s needed to deliver the scale and pace of investment required, and renewed his long-standing call for a carbon price to restore direction and momentum.

How is the proposed solution to the ‘tenor gap’ progressing?

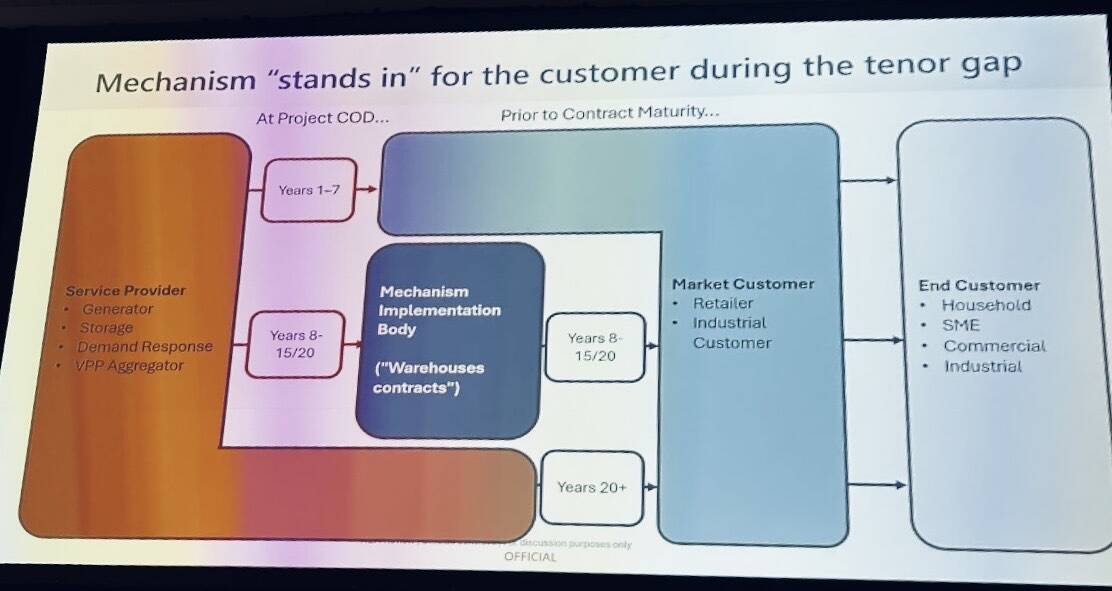

In his speech during the ‘Future Energy Market Design’ session on Day 1, Tim Nelson shared a few new details about the proposed mechanism the panel has begun developing to address ‘the tenor gap’.

Tim outlined a new contract warehousing mechanism that could be implemented by an independent body. He outlined that the set-up would essentially:

- Draw from existing mechanisms/schemes

- Focus on bringing in new investments without messing with competitive neutral pricing for incumbents

- Focus on later years of a project’s operation (e.g. years 8 to 20), thus continuing to allow the market to service the front end of project lifetimes (e.g. years 1 to 7).

- Allow for standardised, fungible contracts to be returned to the market later.

Full details of this proposed mechanism are expected to be released in the coming weeks, as the panel is in the final stages of completing their draft report.

How much closer are we to a data centre wave hitting the NEM?

3 to 4 GW of new capacity, and 12 to 15 TWh of annual electricity consumption, by 2030.

That was the range estimates for future data centre load in the NEM discussed during the Day 1 session ‘Powering Big Data’. But of course, as Joel Gilmore later reminded us during a keynote on Day 2, we must remember the quote “forecasting is hard, particularly when it comes to the future” — so those projections should be treated with healthy caution.

The panel covered a broad range of issues. Outlined below are some of my key observations from what was said during the session:

- AI will drive two distinct load types. As many might already be aware, these are (1) inferencing (e.g. querying) and (2) model training.

- Australia’s AI opportunity is more likely tied to inferencing. Facilities focused on model training can often be located remotely and operated with relatively more flexibility, but Australia will face intense global competition for the latter — particularly in light of recent international policy signals, such as Trump’s proposed ‘big beautiful bill’ which will ease regulatory barriers in the US. Australia may be better positioned to attract inferencing data centres, to meet domestic demand, and given our subsea infrastructure and strong physical connections to Asia.

- The drivers for data centre growth go beyond AI. Morgan Stanley’s Rob Koh highlighted that regulatory shifts (e.g. data sovereignty) and growing cybersecurity needs (e.g. additional redundancy) are also pushing demand for localised data centres.

- Demand response remains a marginal option. Andrew Walton suggested it may serve as a condition to help greenfield projects move through the approvals process. However, inferencing data centres — which are likely to be the dominant type in Australia — are typically bound by service-level agreements (SLAs) that restrict operational flexibility. As NextDC’s Shayne Kumar put it: “Demand response will never be our core business”. In my view, that captures the central challenge demand response has faced since electricity markets were first invented.

- The importance of price signals is contested. Shayne argued that data centre investment will follow cheap electricity. David offered a divergent viewpoint, suggesting that profit margins will be large enough to dull sensitivity to price. Andrew added that many large tech firms have the balance sheets to take more active positions in energy procurement, potentially reshaping how they interact with the grid and perhaps suggesting that they may be more active on the generation-side too.

The most headline-grabbing comments about data centres came during the summit — but not at the summit — from Atlassian co-founder Scott Farquhar’s coincidental address to the National Press Club on Wednesday. One quote in this follow-up ABC article raised both of my eyebrows:

Responding to concerns that the growing number of data centres was already placing strains on Australia’s energy grid, and potentially pushing up power prices, Mr Farquhar said he believed that the increasing and reliable demand for power could have the opposite effect.

“What happens is, as the grid gets larger, it becomes more stable,” he told The Business.

“There’s more points of access putting energy in more, pulling it out, and so the grid can actually become cheaper the more things you connect to it.

“So a grid that powers more data centres, additional to the electricity needs of the nation, is going to be more stable and cheaper.”

Scott Farquhar’s speech sparked a bit of hallway discussion towards the end of the conference — especially regarding the extent to which the data-centre and electricity sectors share a common understanding and direction (and how to align these better).

Which market risks and uncertainties were the focus of this year’s discussion?

From reviewing my notes from the sessions I attended over the two days, the topics that came up most frequently on stage were:

- System stability

- Price forecasting in an increasingly uncertain environment

- The impact of data centres

- Managing minimum system load events

Here I’ll just focus on just the first of those, as it was the one that came up the most.

System stability, and in particular system strength, was a recurring theme. If you attended ‘The Business Case for Large-Scale Storage’ session on Day 2, you might have walked away feeling optimistic that grid-forming batteries will solve many of the stability risks.

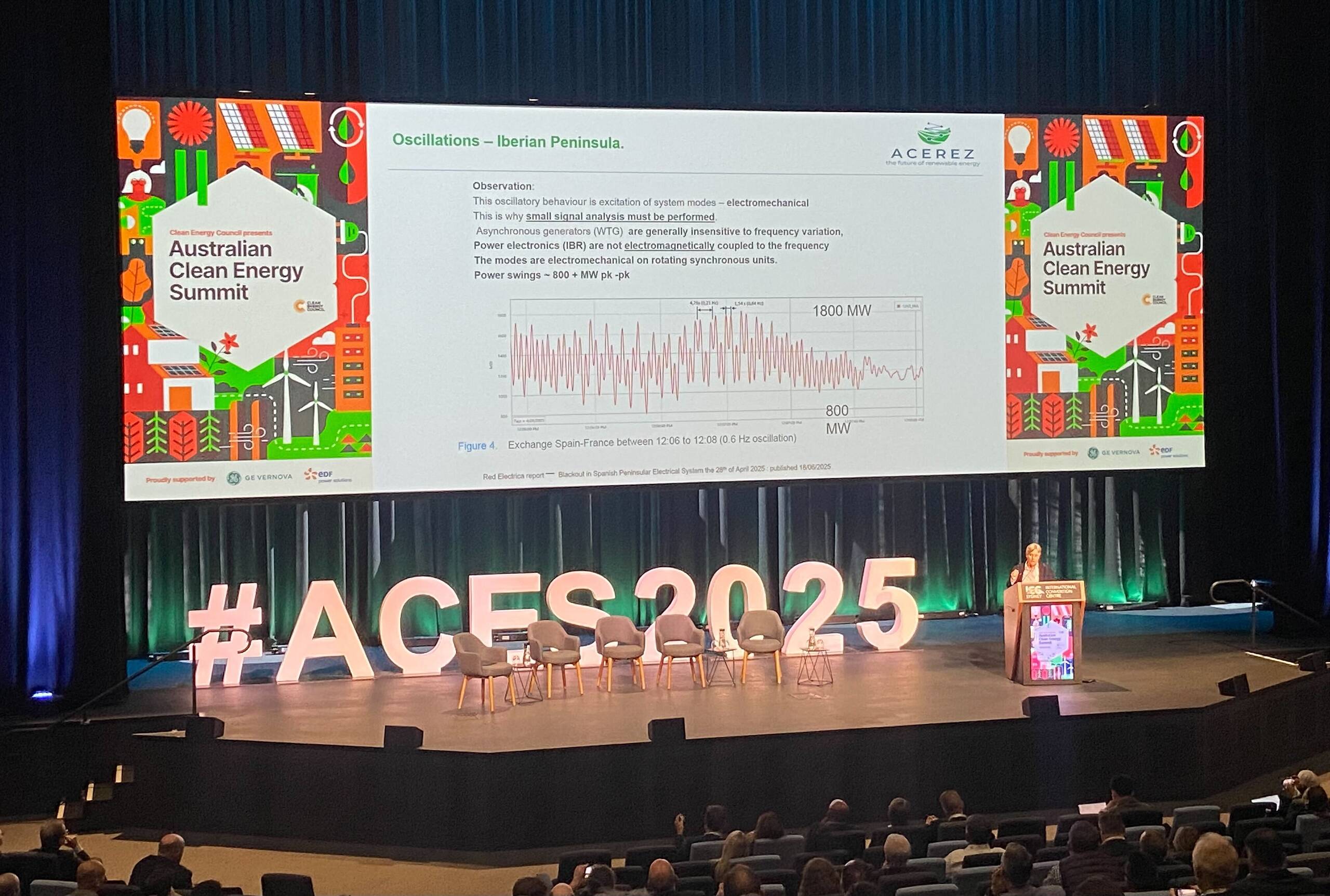

However, the tone was more cautious, and more urgent, in the “Grid Connection & Stability” session held late on Day 1. Kate Summers, presenting on behalf of ACEREZ, delivered a technically rich and candid assessment of rising control and stability challenges in modern power systems, and escalating risk with the rapid deployment of asynchronous generation and power electronics-based systems.

Kate emphasised that engineers must improve their understanding of control systems and frequency-domain methods to anticipate stability issues early—ideally before standard single-machine infinite bus (SMIB) studies are even completed. She noted that the market itself is merely a “gross linearisation of a complex non-linear system” (one of my favourite quotes from the conference), and that technical specifications for market services should be tested against real-world dynamic behaviour.

One slide illustrated the consequences of oscillatory instability during a recent event in the Iberian Peninsula, where 0.6 Hz oscillations between Spain and France caused power swings exceeding 800 MW peak-to-peak. It highlighted the disconnect between traditional modelling assumptions and real-world system behaviour—particularly in systems that are weakly coupled or lack sufficient electromechanical inertia.

Perhaps her most important point was reserved for the end: stability is not just a technical nicety—it’s essential for keeping the lights on, and must be treated as a public good.

—

Many of the answers noted above are far from settled, and we should always try to read between the lines of commercial interest and reality.

As with previous years, the summit proved a worthwhile forum for surfacing tensions, testing ideas, and getting a sense of where the sector’s thinking is headed.

Kate Summers speaks a technical language suitable only for power engineers. However she speaks in such a wonderful and passionate fashion that even amateurs like myself cannot help but be entertained by. It’s no disrespect to her fellow panellists to note that her star shone more brightly.

Also of great interest to me was the session on REZs which was of course the session on transmission.