The final day of 2023 was a notable one in the NEM – although depending on one’s viewpoint it may have been a firecracker or a damp squib.

New Year’s Eve record lows

There were a number of records set, including:

- Lowest-ever half-hourly operational demand levels for:

- South Australia, at -26 MW in the half hour ending 13:30 AEST (NEM time), down from the prior record of 5 MW on 1 October 2023, and the first time this particular demand measure has been negative.

- Victoria, at 1,564 MW in the half hour ending 13:00 AEST, 351 MW below the previous low of 1,915 MW recorded on 29 October 2023.

- Lowest-ever daily average spot price in Victoria at -$73.02/MWh, nearly $20/MWh below the previous daily low. This alone dropped the Victorian quarterly average spot price by nearly 4 per cent to $25.70/MWh.

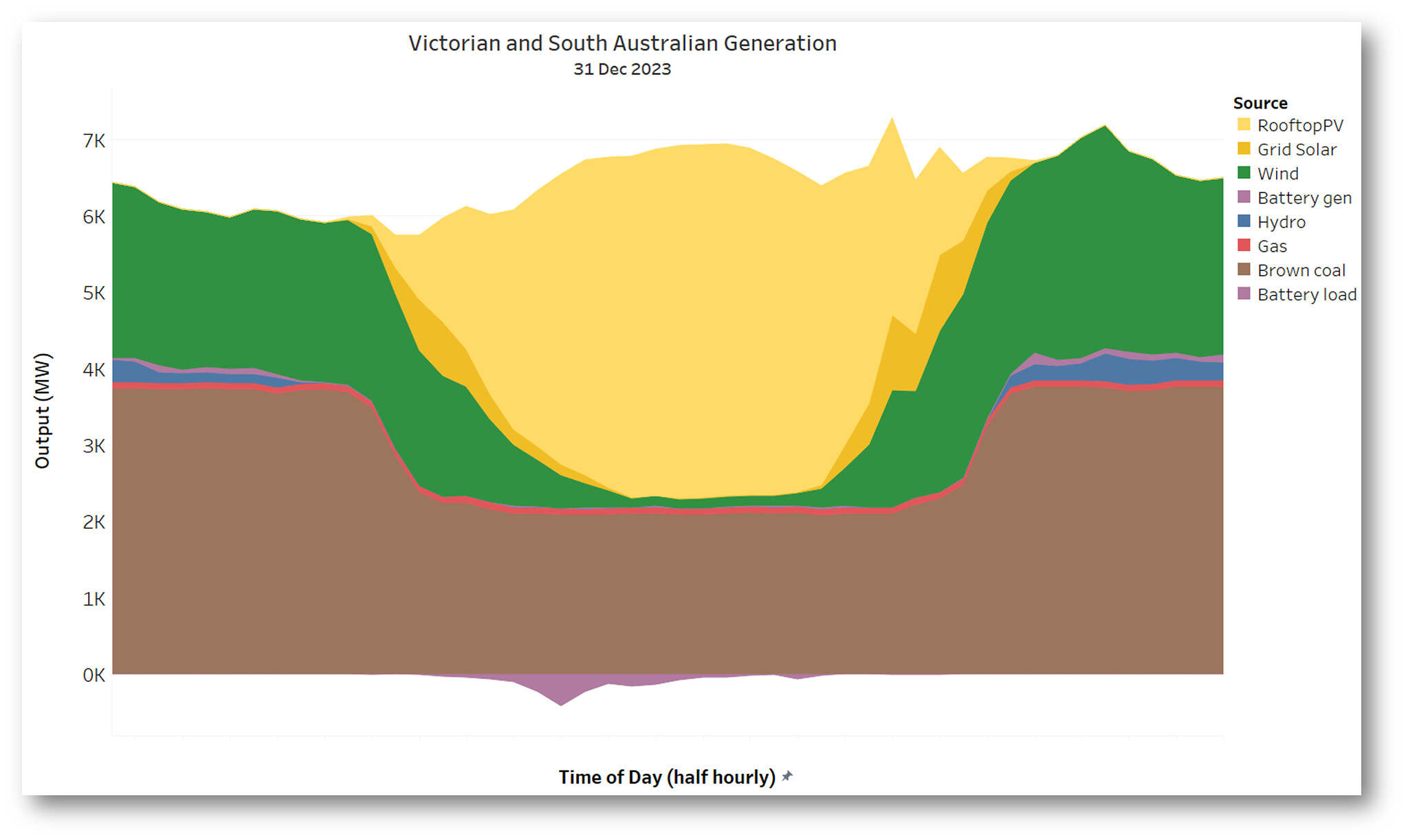

Prices in South Australia and Victoria sat near -$400/MWh throughout the middle of the day. High rooftop PV generation in both regions, almost all of which doesn’t receive or respond to market prices, squeezed out most other forms of generation in this period – including all large scale solar and most wind – other than around 80 MW of gas-fired generation required in South Australia for system strength, and around 2,100 MW of brown coal-fired generation from Victoria’s eight online units, which were forced down to levels likely to be close to their minimum stable output.

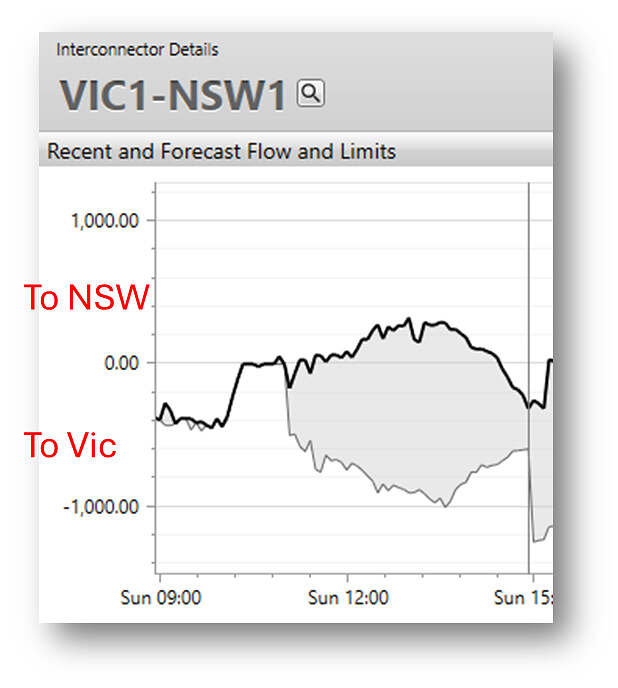

Benign weather kept underlying consumption low, and while Victoria was able to export to Tasmania at maximum levels – around 450 MW – transfers to New South Wales were highly impacted by the Wagga-area constraints I wrote about a few weeks back. This drove the very low spot prices experienced south of the Murray.

New Year’s Eve Puzzles – 1

Picking up on Paul’s series of on-the-day posts, there were a few puzzling features of the day’s events.

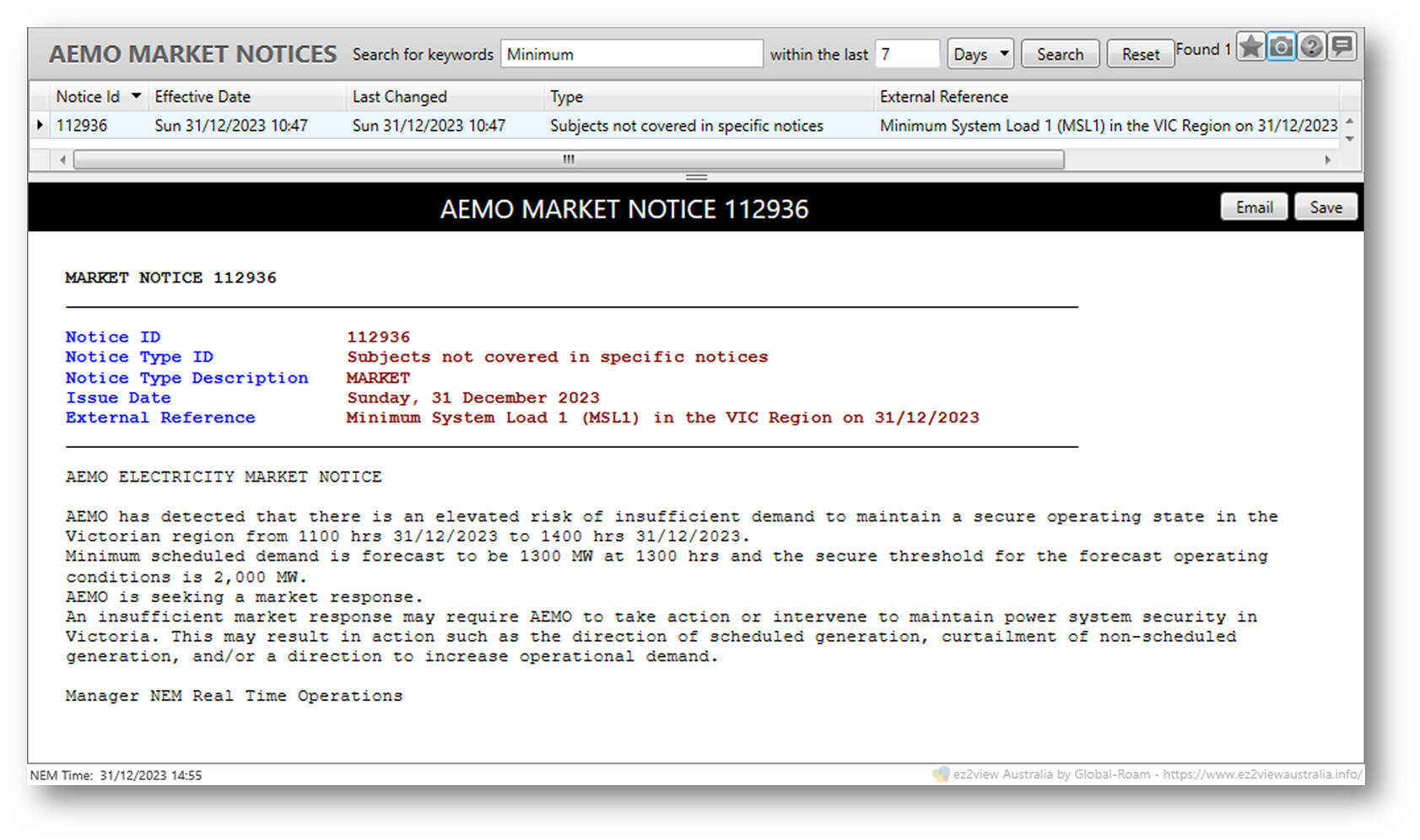

AEMO’s Minimum System Load (MSL1) Market Notice issued at 10:47, alerted readers (including Paul) to “an elevated risk of insufficient demand to maintain a secure operating state”, that the forecast scheduled demand minimum was 1,300 MW, and that “the secure [minimum system demand] threshold for the forecast operating conditions is 2,000 MW”. This was accompanied by the statement that “AEMO is seeking a market response”.

I have no idea what kind of “market response” AEMO was hoping for through this notice. It’s conceivable that a few energy tragics like me were watching events unfold and might have turned on the dishwasher, baked a cake, or recharged the Tesla to take advantage of plentiful solar and the negative prices. Here’s an anonymised screenshot from social media showing how one retail customer on a spot price pass-through contract benefited from the very low spot prices (127 kWh imported! – this person must have a fleet of Teslas!)

But I doubt even efforts like this would have added up in total to much of a “market response” – there simply isn’t enough demand-side flexibility at the moment to make a meaningful dent in minimum demand levels, Victoria has no pumped hydro loads, and large-scale batteries would usually have only very limited storage capability on top of their normal state of charge (evident in the “Battery load” series on the earlier generation mix chart, briefly spiking to over 400 MW but quickly dying away).

Absent a meaningful market response, it’s not clear what else AEMO did about the risk of being unable to maintain a secure operating state in Victoria. Demand levels between 10:00 and 15:00 sat well below the 2,000 MW threshold specified in AEMO’s notice, but there were no further notices about directions or other actions taken.

We can only speculate about the exact nature of the “insecure operating state” potentially brought on by low demand – one guess is that because of the benign underlying demand levels and very high levels of rooftop PV generation, the Victorian load blocks available for automated under-frequency load shedding (AUFLS) shrank in size. That would weaken this “last line of defence” against any very unlikely but high impact event (loss of multiple generators or transmission elements) that crashed the system frequency. Another possibility is difficulties with voltage control, which become more prominent at very low grid demand levels.

It’s certainly possible that despite the market notice, the outturn conditions through the day were such that demand stayed high enough to avoid actual occurrence of an insecure operating state – otherwise we might have expected to see more notices from AEMO about actions taken.

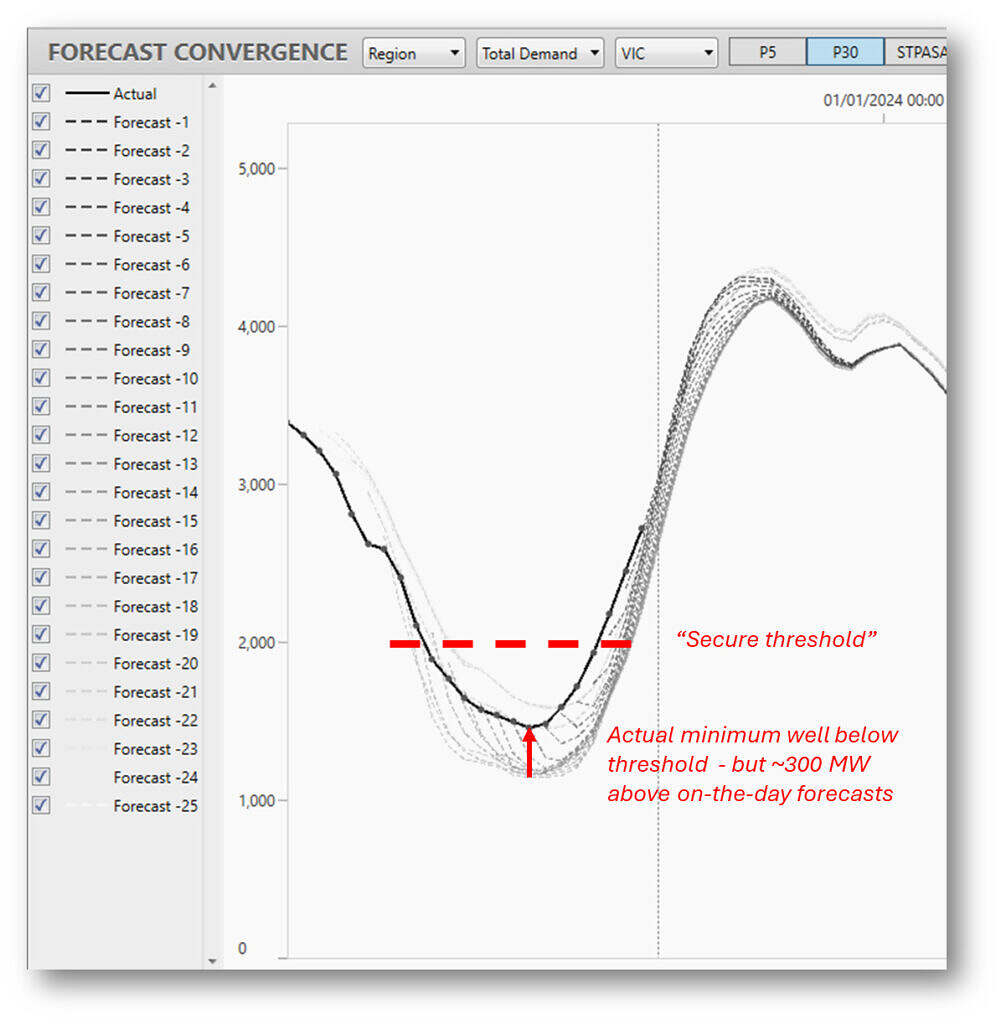

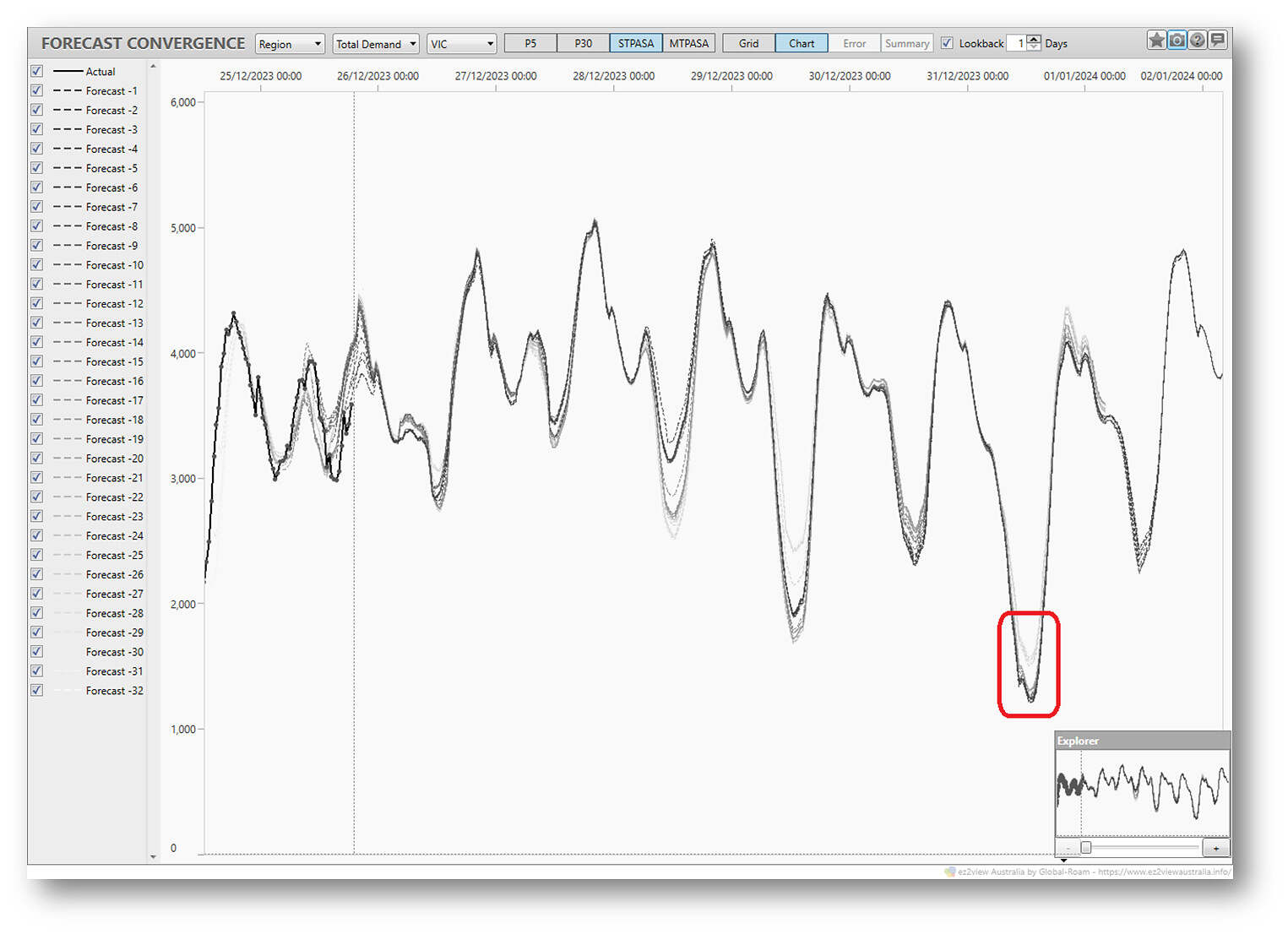

Finally, it’s also a bit strange that this market notice was the first and only one published about this potential issue leading up to the day. AEMO’s Short Term PASA forecasts for demand had been showing consistently the possibility of very low demand on New Year’s Eve – here’s an example of these forecasts nearly a week out, as at Christmas Day:

New Year’s Eve Puzzles – 2

The other puzzle in yesterday’s data is one Paul has already pointed out, and highlighted a couple of charts above, namely that despite falling to a record low level, Victorian demand remained consistently above AEMO’s on-the-day forecasts, which predicted a minimum nearly 300 MW lower.

I don’t really have any firm insights into this, but wonder if there were some behind-the-scenes actions which increased net system demand by lowering output from “small non-scheduled generators” (SNSG) embedded in the distribution system. A fair chunk of this generation comprises large commercial and industrial solar PV installations and mini solar farms ranging in size from 100 kW to just under 5 MW.

- They fall outside the smaller “rooftop PV” class for which AEMO publishes aggregated output estimates and forecasts, but remain below the threshold for registration as grid-scale generators, so there is no public visibility of actual or estimated output from this segment.

- On WattClarity, others have described this category as ‘medium solar’.

There are indications in AEMO’s longer term demand forecast data that this PV SNSG segment might be about 10% the size of the small rooftop PV segment, which was producing peak output of about 3,000 MW in Victoria yesterday. If that’s the case – and this is pure speculation – then full output from the SNSG segment would reduce Victorian grid (“scheduled”) demand by 300 MW.

Reductions in SNSG output could therefore effectively raise grid demand. Perhaps there were such reductions in play yesterday, either as voluntary response to the extremely low spot price, or through actions taken by distribution companies on advice from AEMO? These reductions might not be reflected in the on-the-day scheduled demand forecast, which might partially explain why the lowest demand levels forecast didn’t actually eventuate.

Hopefully the new year will provide some clearer explanations.

=================================================================================================

About our Guest Author

|

Allan O’Neil has worked in Australia’s wholesale energy markets since their creation in the mid-1990’s, in trading, risk management, forecasting and analytical roles with major NEM electricity and gas retail and generation companies.

He is now an independent energy markets consultant, working with clients on projects across a spectrum of wholesale, retail, electricity and gas issues. You can view Allan’s LinkedIn profile here. Allan will be occasionally reviewing market events here on WattClarity Allan has also begun providing an on-site educational service covering how spot prices are set in the NEM, and other important aspects of the physical electricity market – further details here. |

Great summary Alan! Interesting times, particularly with the Victorian emergency solar backstop applying to small scale generation from mid this year.

Still waiting for somebody to explain how wind and solar reduce retail electricity prices.

I feel obliged to point out that a state’s demand met almost entirely by behind the meter solar sees the transmission grid at very low utilisation. But that grid is not paid for by utilisation, it’s paid for by guaranteed returns on the amount of stuff it owns. So it costs the same whether you use it or not.

And since the grid is growing, AND the grid operators now have responsibility for network stability, the costs can only increase.

For some reason nobody talks about it.

It would seem that safe minimum demand was calculated when most generating units were typically 400-700 MW and had response rates of <1% per minute. The loss of one generator or transmission line when only eight were online would be a significant disruption, which would probably trigger further shutdowns, just as the 400 MW loss of Callide C4 led to the loss of 2,300 MW of generation as other units tripped off to protect themselves from instability.

Now however, not only batteries and the newly installed syncons but curtailed wind and solar facilities can respond within milli-seconds. In addition, the tightening of primary frequency control requirements on conventional generators means that gas, coal and hydro plants also respond more quickly to disturbances. Thus, the minimum safe level of generation will gradually decline in Victoria, then NSW and Queensland, just as it has declined from 250MW to 80 MW in SA.

In fact, it is clear that SA can already run on zero gas for hours if not days at a time but the risk of a mistake both in short term load shedding and the long-term political risk to the whole transition are not worth the benefit of saving 80 MW of gas generation.

Similarly, because across Victoria and SA it appears around 600-800 MW of wind and solar was being curtailed and in Tasmania and Victoria 4,300 MW of hydro was only running at less than 500 MW while batteries were actually drawing power, it is quite possible that Victoria/SA/Tasmania could have run at 100% renewables for at least four hours if Victoria's coal plants were flexible enough.

Thanks Peter

I don’t think the minimum demand issue is to do with loss of a large unit – Victoria is strongly interconnected to three other regions and frequency control wouldn’t be the problem. I’m still inclined to think it’s something a bit more arcane like voltage control, or Victorian AUFLS becoming ineffective because many distribution feeders would be carrying only small net loads with relatively low demand but high rooftop PV generation.

Allan

“an elevated risk of insufficient demand to maintain a secure operating state”

Shouldn’t that be

“an elevated risk of over supply to maintain a secure operating state”

Do the curtailed wind and solar farms get paid for production loss?

Hi Peter – I think the AEMO wording is appropriate. Potential oversupply is readily managed – at worst AEMO could direct generation off; on the other hand issues like voltage control or impairment of AUFLS capacity are related to low operational demand, not excess large scale supply.

Wind and solar was not curtailed in most cases – they simply offered their output to the market at prices not low enough to get dispatched. Nor would they want to have been dispatched at -$400/MWh. Generation curtailment (resulting from network constraints) does not get compensated in the NEM in any case.

Allan