This article was originally posted on WeatherZone where there are other comments.

Australia’s severe weather season runs from October to April and typically features a mix of heavy rain, thunderstorms, heatwaves, bushfires and tropical cyclones.

When predicting how the 2021/22 severe weather season will unfold, we look at the broad-scale climate drivers that are likely to influence Australia’s weather during the next 3-6 months.

In recent years, there has been a strong background influence from some of these climate drivers. For example, the years between 2017 and 2019 were dominated by drought, heatwaves and bushfires, underpinned by El Niño and a strong positive Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD).

Last summer, a weak La Niña saw more rain and thunderstorms returning to the landscape, which helped replenish some of the rainfall deficiencies that had built up in recent years. Last season’s bushfire activity was also suppressed by some of the coolest and wettest weather of the last decade.

This year, we are entering this severe weather season without any strong climate drivers at play. As a result, the season got off to a slow start in September, however storms have become more active in the last fortnight.

We have also seen some intense early-season heat in northern and eastern Australia. Brisbane reached 36.6ºC on Monday, October 4, which was hotter than any day the city had last summer. One day later, Western Australia’s Wyndham Airport hit 43.7ºC, which is the highest temperature seen anywhere in Australia, this early in spring, since 1988.

So, with a spike in early season heat and storm activity starting to ramp up, what can we expect to see across Australia during the 2021/22 severe weather season?

Climate Drivers

IOD

The Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) is defined by the gradient in sea surface temperatures between the eastern and western tropical Indian Ocean. While the IOD can have a big influence on Australia’s weather in winter and spring, it usually breaks down by the start of summer.

A negative IOD event that occurred during winter and early spring has now weakened, with the IOD index returning to neutral territory during the past month or so. This event is likely nearing its end and most models predict that it will break down before the start of summer.

Image: Typical impacts of a negative IOD.

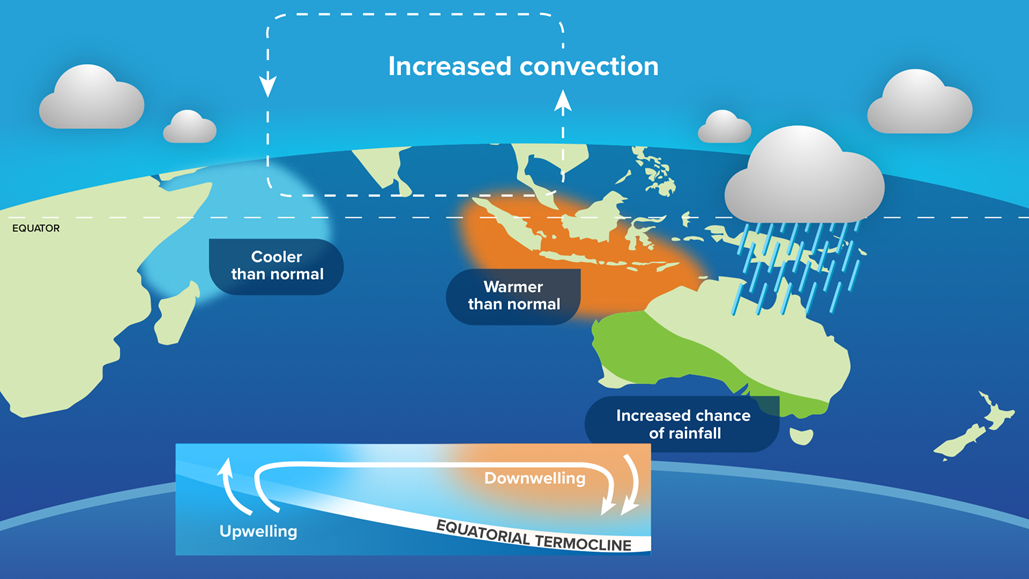

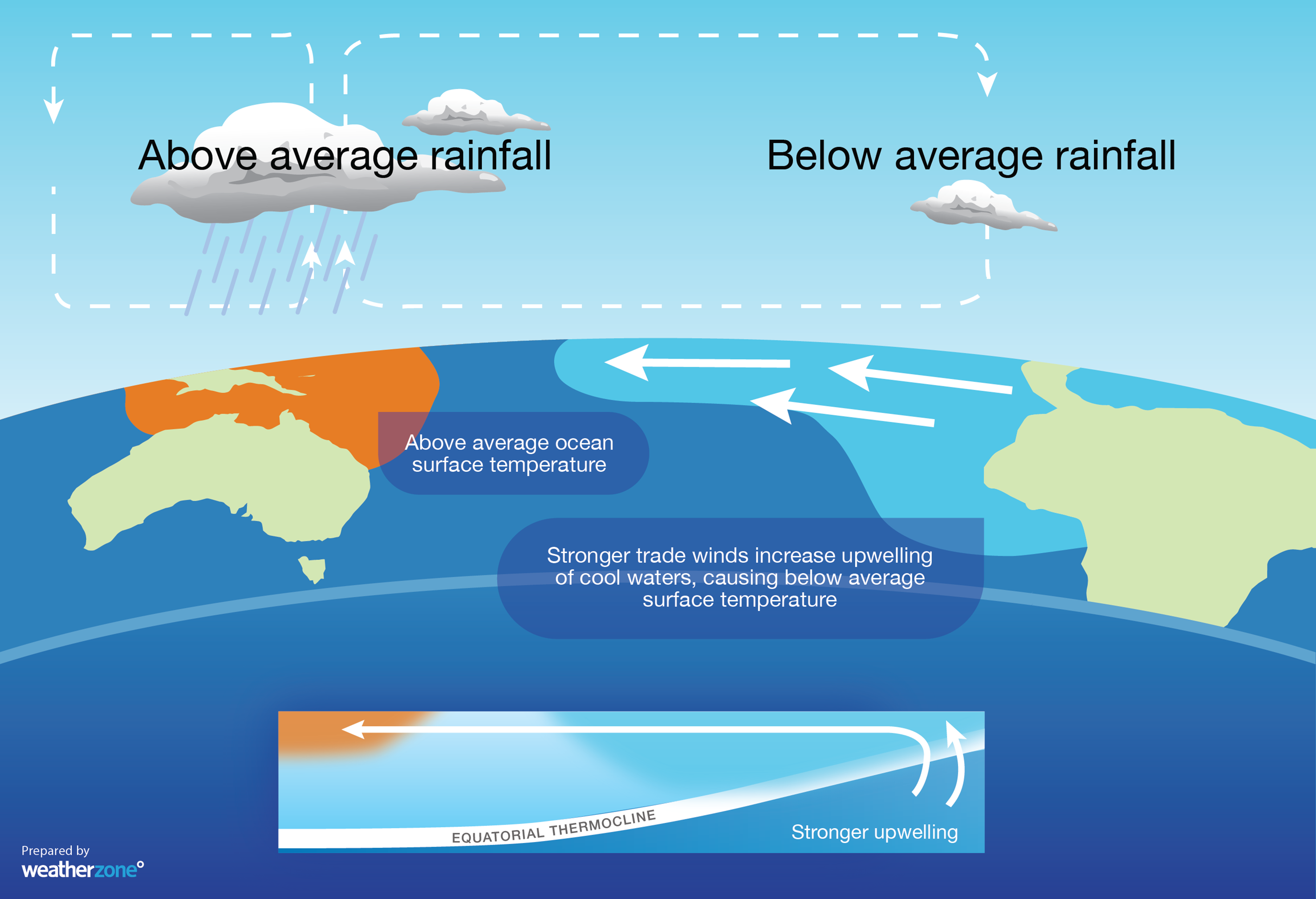

ENSO

The El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is the oscillation between El Niño, La Niña and neutral conditions in the Pacific Ocean. El Niño typically produces drier and warmer weather in Australia, while La Niña drives wetter and cooler years.

The ENSO is currently neutral. However, cooling has been observed in the central and eastern Pacific Ocean, indicating the potential for a weak La Niña in the coming months. This would be the first back-to-back La Niña in a decade.

Image: Typical impacts of La Niña.

If La Niña does form later this year, it is likely to be on the weaker side compared to last year and the strong 2010-2012 La Niña event. It’s also likely to be short-lived and have less influence during the second half of the severe weather season.

SAM

The Southern Annular Mode (SAM) is an index that measures the north-south displacement of the westerly winds that flow between Australia and Antarctica.

When the SAM is in a negative phase, westerly winds and cold fronts are located further north than usual. This typically causes more cold outbreaks along increased wind power and rainfall for southern Australia. However, negative SAM can also cause drier-than-usual weather in eastern Australia during summer.

On the other hand, a positive SAM usually causes more heatwaves and reduced wind power and rainfall in southern Australia during spring and summer. In eastern Australia, rainfall is typically above-average when SAM is positive in late spring and summer.

Image: Typical impacts of a positive SAM.

Unfortunately, the SAM is much harder to predict beyond the next fortnight compared to the other two climate drivers mentioned above. However, a strong polar vortex over Antarctica earlier this year is likely to have a lingering influence on the SAM in the coming months, making positive SAM phases more likely until at least December. Positive SAM episodes are also more likely when La Niña is active in the Pacific Ocean.

MJO

The Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO) is an eastward pulse of cloud and rainfall that moves around the globe near the equator every 30 to 60 days.

When it is active near the Australian region, it usually increases rainfall, storms, and tropical cyclone activity across northern Australia. Conversely, when the MJO is away from Australia, a reduction in rainfall, storm and cyclone activity is typically observed.

Image: The eastward movement of the MJO causes an increase in rain and thunderstorm activity over Australia when it moves through near the Australian region.

The MJO can be predicted up to about two weeks ahead and is a great forecasting tool for thunderstorms, rainfall and tropical cyclones.

The MJO is currently moving through the Australian region and some models suggest that it could enhance rainfall across northern Australia during the first half of October, before moving away.

Climate change

In addition to the climate drivers mentioned above, which change state from year-to-year, Australia’s severe weather season is also influenced by the background effects of climate change. Some of the observed changes in recent decades include:

- Australia’s climate has warmed by 1.44ºC over the last 110 years.

- This warming has caused an increased frequency of extreme heat events.

- There has been an increase the severity and length of Australia’s bushfire season.

- The number of tropical cyclones observed in the Australian region has decreased over the last three decades.

- Northern Australia has seen an increase in wet season rainfall during the last 20 years.

- Heavy rainfall events have become more intense in some parts of Australia in recent decades, particularly in the tropics.

- Research has shown that positive phases of the SAM have become more common in recent decades.

Impacts this season

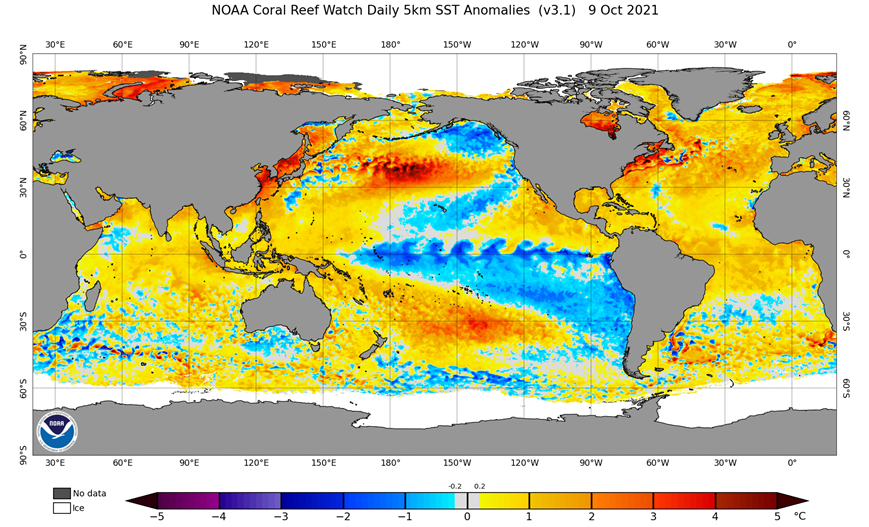

With no strong climate drivers in the mix, the most dominant influence on Australia’s weather this season may come from local sea surface temperature anomalies and the Pacific Ocean, where a weak La Niña could develop. There will also be periodic contributions from the SAM and MJO, along with the background influence of climate change.

Image: Global Sea surface temperature anomalies on October 9, 2021, showing a distinct La Niña-like pattern in the Pacific Ocean and abnormally warm waters around northern Australia.

Temperatures

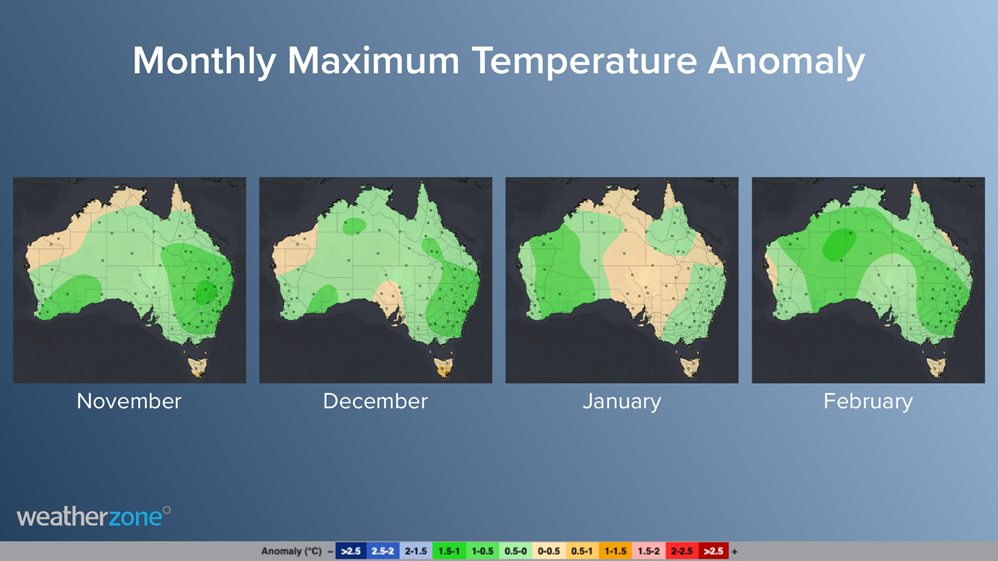

Overall, this severe weather season is likely to be warmer than last season, but not quite as extreme as 2019/20.

The tail end of this year’s negative IOD and the prospect of a weak La Niña decrease the likelihood of extremely hot days during spring and early summer. However, heatwaves are more likely in southern Australia during La Niña seasons, but they are generally not as intense as El Niño years.

The number of days above 35ºC are likely to be near or slightly below average for most capital cities in southern and eastern Australia.

Image: Forecast maximum temperature anomalies for Australia during the next four months.

It’s also worth noting that tropical cyclones forming off the northwest shelf of Australia have been linked to heatwaves across southeastern Australia.

Tropical cyclones

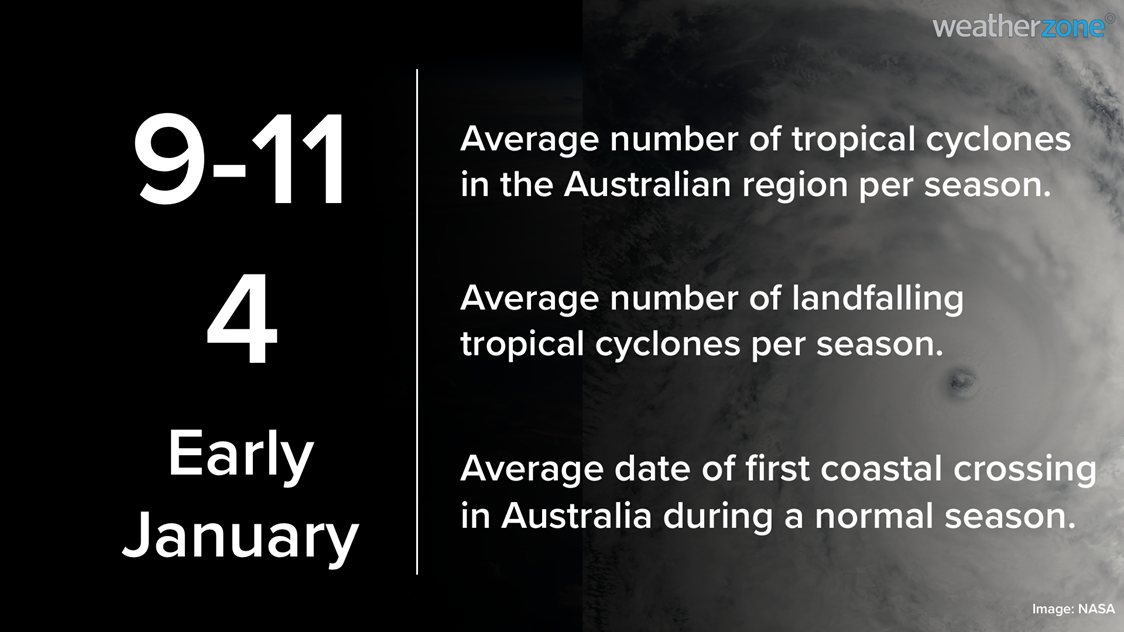

Australia’s tropical cyclone season runs from November until April. During this time, we usually see 9 to 11 tropical cyclones in Australia’s area of responsibility, four of which usually make landfall.

This season, tropical cyclone activity is likely to be near or slightly above average in the Australian region.

Image: Statistics for Australia’s tropical cyclone season, which runs from November until April.

This outlook is being driven by warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures near northern Australia and the potential for a weak La Niña this summer.

During a normal year, the first tropical cyclone of the season to make landfall usually occurs in early-January. However in La Niña years, the first coastal crossing typically happens in mid-to-late December.

The tail end of this year’s negative IOD may also increase the likelihood of early-season tropical cyclone development.

Rain

Widespread rain, thunderstorms and flooding are an increased risk during the rest of spring into early summer for most of Australia. This is due to the negative IOD and potential La Niña, along with generally above-average sea surface temperatures near northern Australia.

Some areas of eastern and southeastern Australia have entered spring with abnormally high amounts of soil moisture following good mid-year rainfall. This wet landscape will increase the likelihood of riverine flooding in the coming months, especially in areas that receive above-average rain.

Elevated levels of moisture in the atmosphere will also increase the risk of flash flooding from thunderstorms, particularly in spring and early summer.

Thunderstorms

Thunderstorms require three key ingredients to develop:

- Sufficient moisture in the lower levels of the atmosphere.

- Instability in the atmosphere.

- A trigger to initiate the storm.

During spring and early summer, La Niña, locally warm sea surface temperatures and positive phases of SAM should increase the amount of moisture available to fuel storms across much of the country.

However, positive SAM and La Niña can also reduce the instability and triggers required for storm development, particularly in southern and eastern Australia.

This should result in near-to-below normal thunderstorm activity in southern and eastern Australia between October and December, with more normal storm activity likely to return early next year.

While the overall number of thunderstorms may be reduced in eastern Australia this season, severe storms are still likely to produce large hail, damaging wind and heavy rain.

It’s also worth noting that if a fully-fledged La Niña event doesn’t come to fruition, storms will likely be more frequent and intense over Australia’s eastern states. This is because neutral ENSO conditions provide the most favorable setup for thunderstorm activity in Australia.

Elsewhere, northern and western Australia could see near-to-above average thunderstorm activity during the next 2-3 months, under the influence of a weakening negative IOD and increased moisture in the tropics.

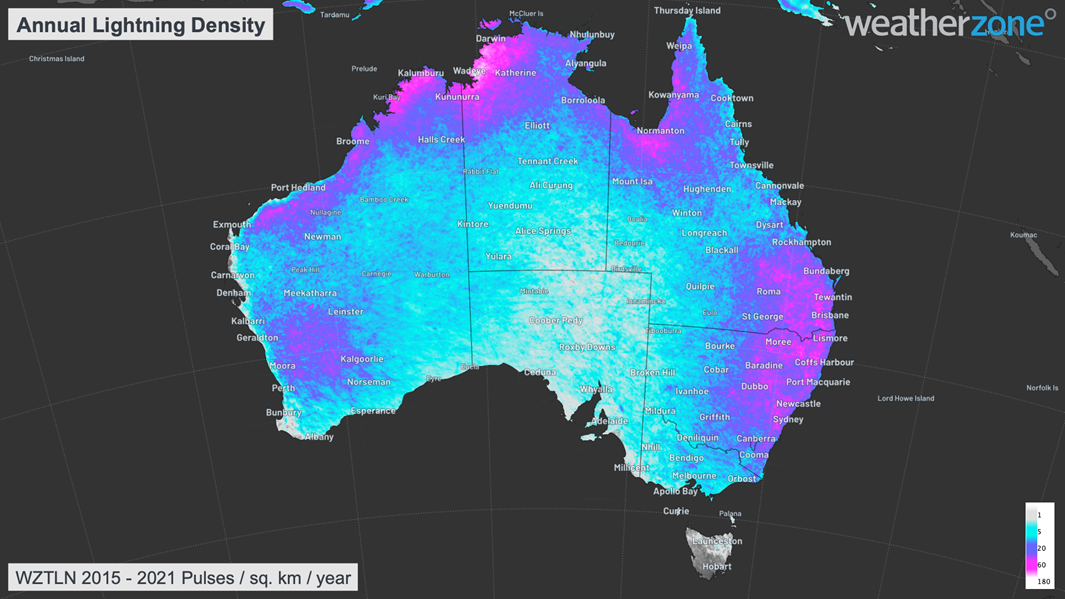

In an average severe weather season, thunderstorms affect every state and territory in Australia. However, there are several distinct lightning hotspots, most notably in the western Top End and eastern Kimberley, and across southeast Queensland and northeast NSW.

Image: Average annual lightning pulse density for Australia, using data collected by the Weatherzone Total Lightning Network between 2015 and 2021.

Northern Wet Season

The warm oceans around Australia are conducive to high humidity air and above average rainfall in the next three months across northern Australia, particularly for the NT and QLD.

An early monsoon onset is forecast for Darwin in the 2021-22 wet season, due to the negative IOD and possible La Niña event.

If La Niña were to form this year, rainfall totals during the wet season are also more likely to be above normal.

Fire

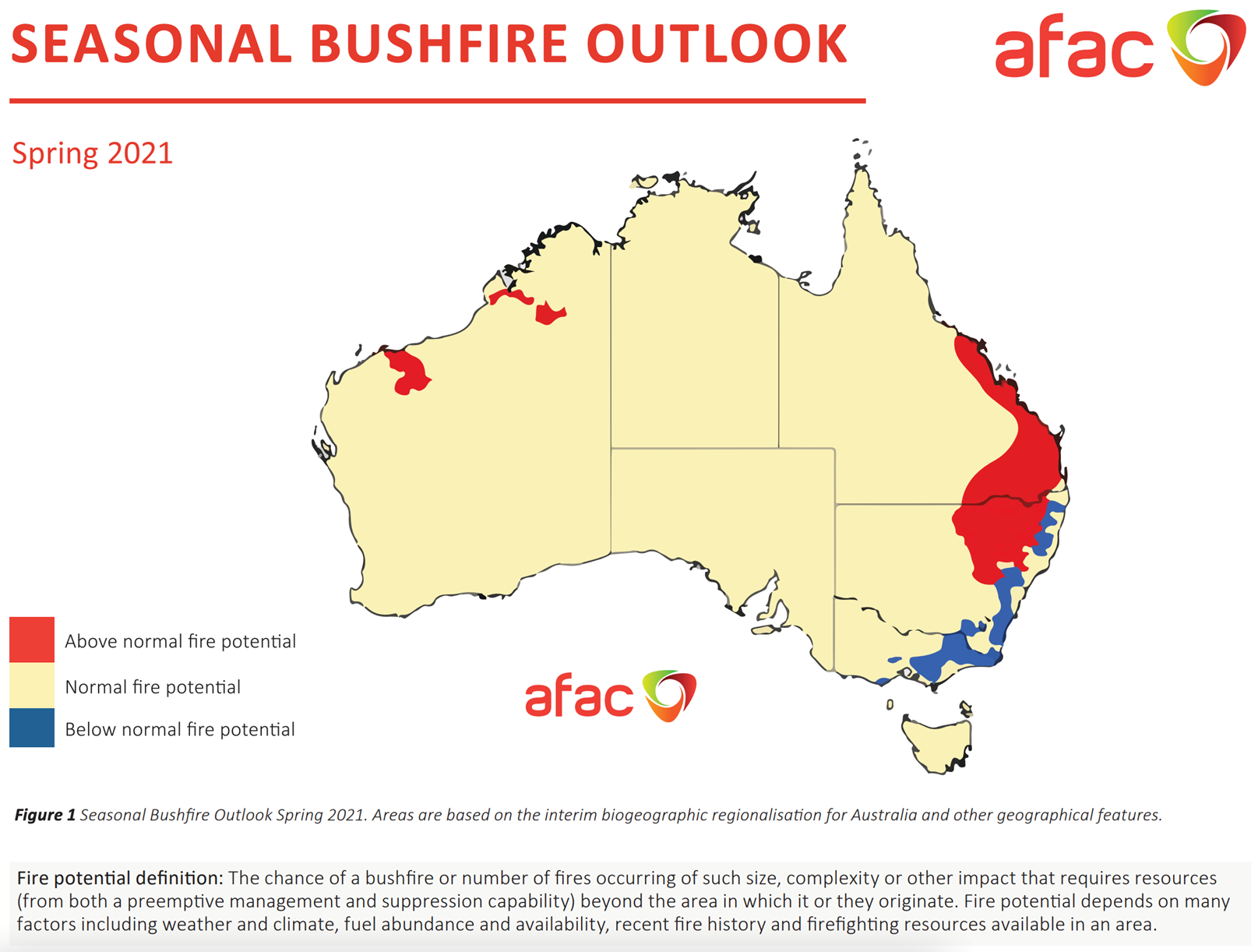

There will be an increased risk of grass fires over a broad area of eastern Australia, stretching from central Queensland down to central inland NSW, during the first few months of this season. This region has seen prolific grass growth in recent months after good mid-year rain and once this grass dries out, it will produce high fuel loads for fires.

But while grassfires could be more active than usual in parts of central and northern NSW this spring, the bushfire potential will be suppressed in areas that were scorched during the Black Summer fires a couple of years ago.

The blue areas on the map below, which are scattered from northeast NSW down to southern Victoria, include these burnt-out areas that have a below-normal bushfire potential this season.

Image: Bushfire Seasonal Outlook for spring 2021, issued by AFAC.

As we head into summer, the absence of any strong climate drivers means we have roughly an equal chance of above and below-normal fire potential for most of the country. However, this fire season may be more active than last season, but it will not be as severe as the Black Summer of 2019/20.

The Australian Fire and Emergency Services Authorities Council (AFAC) will release an updated national bushfire outlook before the start of summer.

Wind

Strong wind events are likely to be less frequent in southern Australia until at least the end of this year. This is due to the increased likelihood of positive SAM episodes in spring and early summer, and the associated suppression of cold fronts and low pressure systems across the nation’s southern states.

While strong wind events are less frequent during La Niña and positive SAM, cold fronts and storms are still likely to move through and cause periods of increased wind this season.

If La Nina does occur, it is predicted to be short-lived and should end by around January or February. This would increase the prospect for more periods of negative SAM and stronger wind events during the second half of summer into early autumn.

Cloud

Cloud cover is expected to be above average in northern Australia this wet season, due to above-average sea surface temperatures causing increased evaporation in the tropics.

Increased cloudiness is also likely in eastern Australia between October and December, driven by enhanced onshore winds from a potential La Niña and predominantly positive SAM.

This increased cloud cover is likely to reduce solar output across much of the country, particularly across the eastern states in spring and early summer.

Solar output may return closer to normal during the second half of summer as La Niña breaks down and positive SAM becomes less likely.

Summary

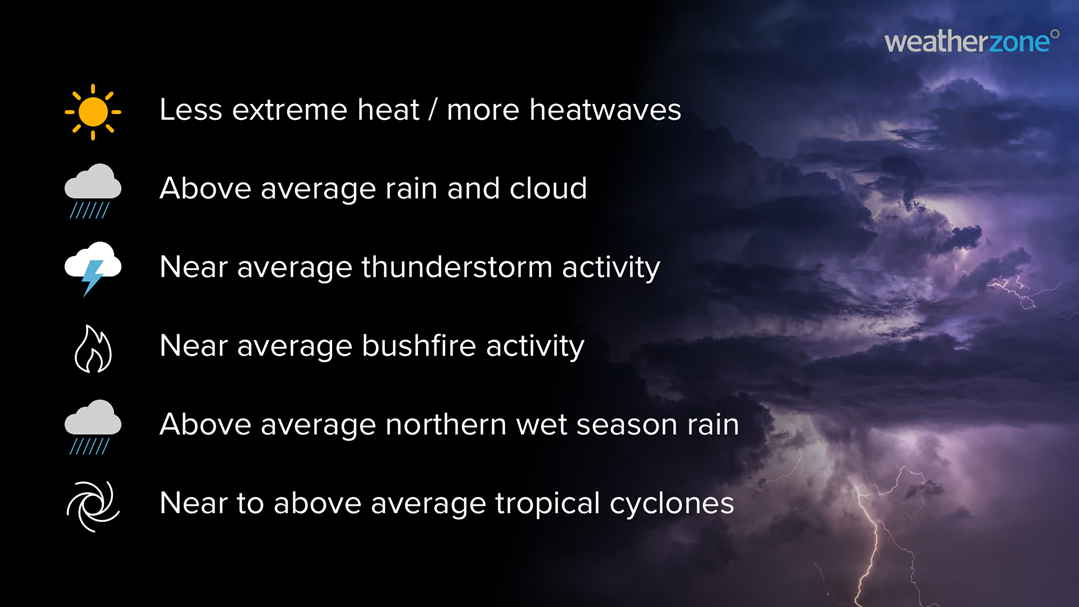

In summary, this severe weather season is likely to be warmer than last season but not as hot as 2019/20. Extremely hot days are less likely, while prolonged heatwaves are an increased chance.

Rainfall and cloud cover should be above average for much of the country in spring and early summer. This will help suppress bushfire activity for most of Australia, except areas of the east that have seen prolific grass growth earlier in the year.

Thunderstorms may be less active overall this season if La Niña develops. However, there will still be outbreaks of severe storms, and heavy rain and flooding are an increased risk when storms do develop.

The northern wet season should start early and bring above-average rain and thunderstorms to the tropics. Likewise, the tropical cyclone season may start earlier than usual and should bring a near-to-above average number of named tropical cyclones between November and April.

Strong wind events are less likely in southern Australia during the rest of this year but may return to more normal levels in the second half of summer.

Weatherzone will continue to monitor the state of Australia’s climate drivers over the coming months. We provide detailed monthly seasonal long-range information to our clients, which is specific to their business operations. If you have any questions or would like more information on Weatherzone’s long range forecasting, please contact us at business@weatherzone.com.au or through LinkedIn.

======================================================================================================

About our Guest Author

|

Ben Domensino is a Communications Meteorologist at Weatherzone.

Weatherzone, a DTN company, is Australia’s largest private weather service and was established in 1998. Their team of highly qualified meteorologists understands the effect the weather has on the day to day operations of businesses of all kinds. They also run Australia’s most popular consumer weather website and mobile app. Weatherzone provides market-leading weather insights to more than five million Australians and over 15 industries, including energy, mining, agriculture, ports, aviation, retail, insurance, broadcast media and digital media. You can find Weatherzone and Ben Domensino on LinkedIn. |

Be the first to comment on "Severe Weather Season Outlook – 2021/22"