Updated Article – note that this was originally posted late Wednesday 5th March, but was updated subsequently based on some great early feedback from a bunch of readers.

———

A couple days ago we posted ‘Watt’s Within a Dispatch Interval? A *very* simplistic view, for a start…’, which itself followed on from ‘Three of the common building blocks within the National Electricity Market’.

… it’s taken a bit longer than initially envisaged to piece this series of articles together due to a number of factors (including Mother Nature).

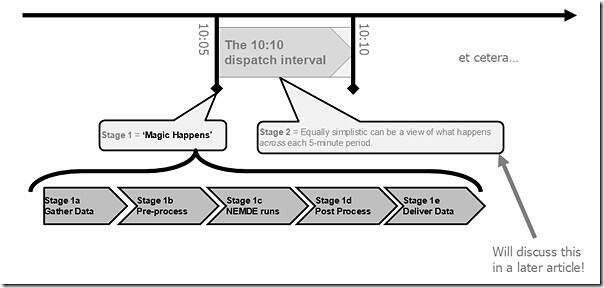

In the second article we deliberately presented a very simplified (very simplistic) illustration of what happens within a dispatch interval, during which we separated a dispatch interval into two stages as follows:

Stage 1 = at the commencement of each dispatch interval we noted:

‘A very simplistic view is that we might assume that ‘Magic Happens’ within an infinitesimally small instant in time between the prior dispatch interval and the next one (to produce Prices, Dispatch Targets, and other Outputs).’

Stage 2 = which meant that the simplistic view holds that there’s a contiguous 5 minute period…

‘Equally simplistic can be a view of what happens across each 5-minute period.’

With that starting point now, in this article we’ll focus in just on ‘Stage 1’ above to try to peel a few layers of the onion beneath that simplistic ‘Magic Happens’ label….

(Some of) What actually happens within ‘Magic Happens’, at the time border of each dispatch interval

It’s still a simplification (although less so than in the second article) but I think of what happens within that ‘Magic Happens’ label as four (now five) sequential steps:

Each of these we’ll briefly outline and explore here…

| Sub-Stages within ‘Magic Happens’ |

Some brief notes |

|---|---|

1a) Gather Data |

There’s a wide range of data that the AEMO monitors (via different sources and using different technologies) on a continuous process as part of its ‘keeping the lights on’ function. However leading into a Dispatch Interval (i.e. just prior to the end) there are processes at work to ‘snapshot’ this data for the purposes of ‘operating the market’. At this point I would particularly like to highlight three different types of data: Type 1 = The AEMO does a sweep of the SCADA data that is streaming into its Energy Management System (a) this includes for unit outputs: i. specifically, a snapshot becomes the ‘Initial MW’ for all of these units (i.e. Scheduled, Semi-Scheduled and some significant Non-Scheduled units) very close to the end of the prior dispatch interval. ii. this data source for this is also the data source used for the 4-second SCADA data set (on the occasions we’ve looked, they have lined up with the 4-second snapshots at the HH:MM:00 timestamp, but we’ve not checked comprehensively) (b) but remember that there’s a whole heap of other network data that is also included in the SCADA data set from its EMS (including line flows, dynamic ratings, equipment statuses etc – goes into constraint RHS calculation in 1(b) below) Type 2 = Bid Data. Remember that with bids: (a) Price Bands are snapshotted at Gate Closure #1 (b) But Volume in these price bands can be changed up until Gate Closure #2 Type 3 = UIGF from a self-forecast (if in use). In this case, this data is captured prior to Gate Closure #3. … noting that UIGF from the AEMO’s own AWEFS/ASEFS systems is more like Stage 1b below.

|

1b) Pre-process Data |

NEMDE (the NEM Dispatch Engine, which used to have an acronym shortened to ‘SPD’) is a linear-programming based dispatch optimisation engine. It utilises a large set of ‘Constraint Equations’ that contain:

There are a number of things that are not calculated within NEMDE itself, including the following: 1) Calculation of the RHS for all invoked ‘Constraint Equations’ I’d initially just noted this one here, but readers have suggested I also note some others below as well (thanks!). (a) Sometimes these RHS formulations contain ‘feedback terms’ (which means the state of the terms that are on the LHS, but at the start of the dispatch interval).

(b) We’ve come across these feedback terms in Case Studies previously here on this site. Links to be added later, as time permits.

I particularly wanted to emphasise this pre-processed data as part of this article. 2) Target (i.e. forecast) for ‘Market Demand’ at the end of the Dispatch Interval. I’d initially just noted this one here, but readers have suggested I also note some others below as well (thanks!). This is calculated outside of the LP solve and involves machine learning and other techniques that the AEMO has assembled (and improved over time … albeit this task is also growing more complex given ‘energy users’ are less and less a homogeneous bunch). |

1c) NEMDE crunching |

We’re not going to delve into more levels of complexity here … so, for the sake of this article, let’s just assume that the NEMDE process itself (i.e. the LP-based dispatch optimisation) is a ‘Black Box’ that:

Learned readers have also suggested it’s worth pointing out that NEMDE runs multiple times in each dispatch interval (e.g. fast start commitment, Basslink frequency controller status) |

1d) Post-Processing |

Readers have suggested I also note explicitly about some post-processing functions such as:

|

1e) Deliver Data |

This data then needs to be delivered to all participants and stakeholders:

The MarketNet process works via a ‘Batcher and Loader’ infrastructure to enable clients to update their own EMMS database (which AEMO officially fully supports in MS SQL and Oracle … older NEM junkies might remember it as InfoServer). |

So how long does this take?

Readers will understand that the above can’t take an ‘infinitesimally small instant in time between the prior dispatch interval and the next one ’.

I don’t have time to go into all the details here (perhaps we’ll crunch and report some stats as a subsequent article) but for illustration purposes let’s just say:

1) This whole ‘Magic Happens’ process takes about ~35 seconds to achieve … end to end, with:

(a) Some time before the end of the prior dispatch interval accounted for in Gate Closure #2 and Gate Closure #3, and also some of the other data gathering.

(b) But it’s also ~20 seconds into the next dispatch interval before participants receive their Targets and Enablement Levels

… Which means that we’re ~6.67% into the next Dispatch Interval before participants receive their Targets … which is a segue into understanding ‘(A second step into the complexities of) the Dispatch Interval in the Real World’ (link coming soon).

2) But keep in mind that this is just for dispatch data … it’s a whole other can of worms for other data sets, with P5MIN data latency being even more complicated (and occasionally much, much slower).

But that’s where we have to leave this article…

Leave a comment