On Wednesday afternoon, Linton and I presented to the Clean Energy Council’s Market, Operations and Grid Directorate about the Capacity Investment Scheme (CIS). It was a pleasure to be invited back to speak with that group, and we thank Veronika Nemes, Diane Staats, and the CEC for the opportunity.

The presentation summarised our recent four-part WattClarity article series on the CIS and related state-based schemes:

- Part 1: Tracking the progress of CIS projects post-award

- Part 2: Understanding why there are delivery challenges

- Part 3: Treatment of curtailment risk

- Part 4: Policy lessons highlighted by the Nelson Review

Since publishing that series, we’ve received a generous amount of feedback from across the NEM — from consultants, policy makers, analysts, developers, and many others. Given that many projects (including many whom were awarded their contract 12+ months ago) are still yet to reach Financial Investment Decision (FID), a wide range of people came to us keen to share their views on why progress under these schemes appears to have been slower than expected so far.

Those conversations helped shape our own views, so this article summarises a few of the key themes we explored in yesterday’s presentation, and lists some of the open-ended questions we continue to ponder.

Battery development dwarfs VRE development

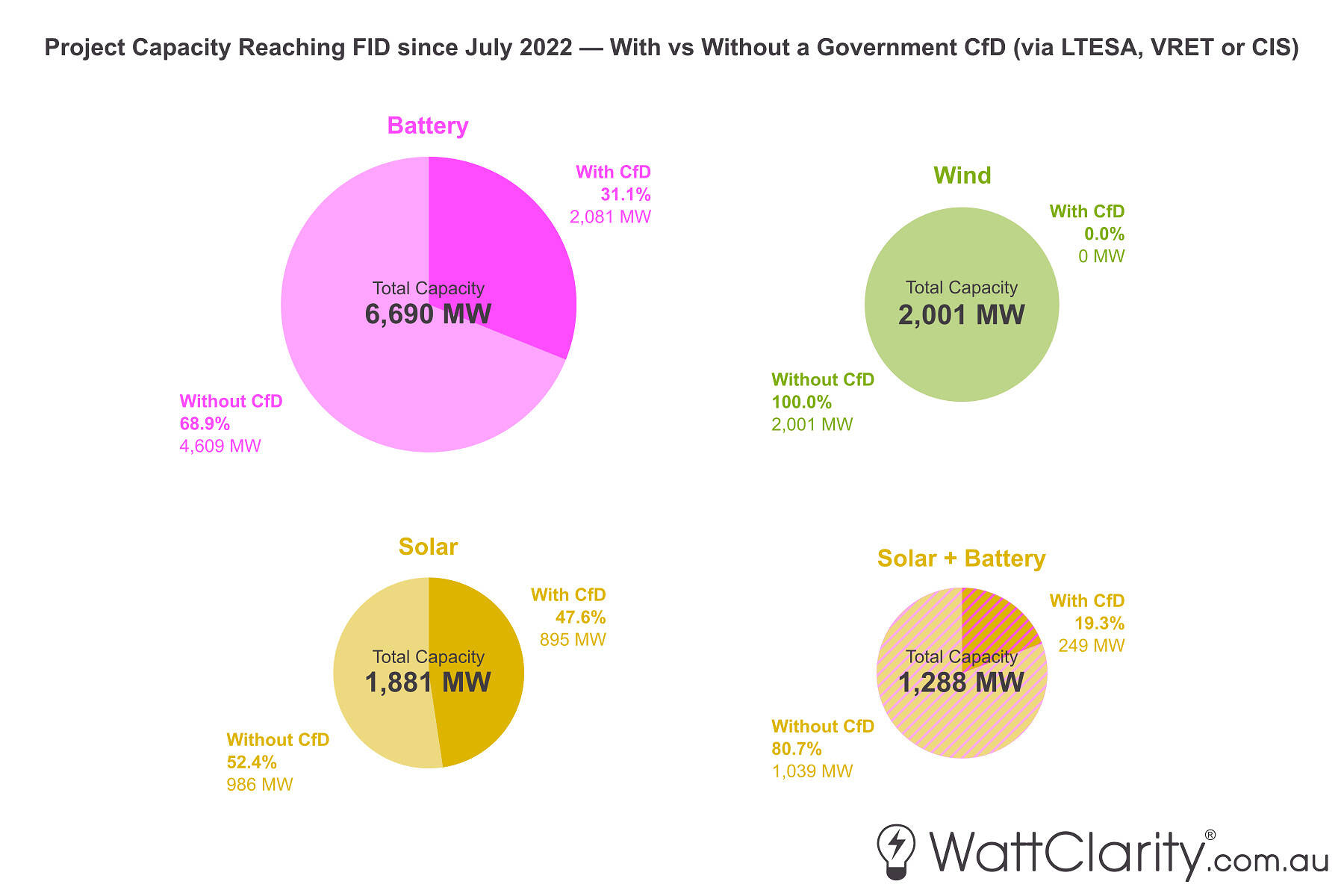

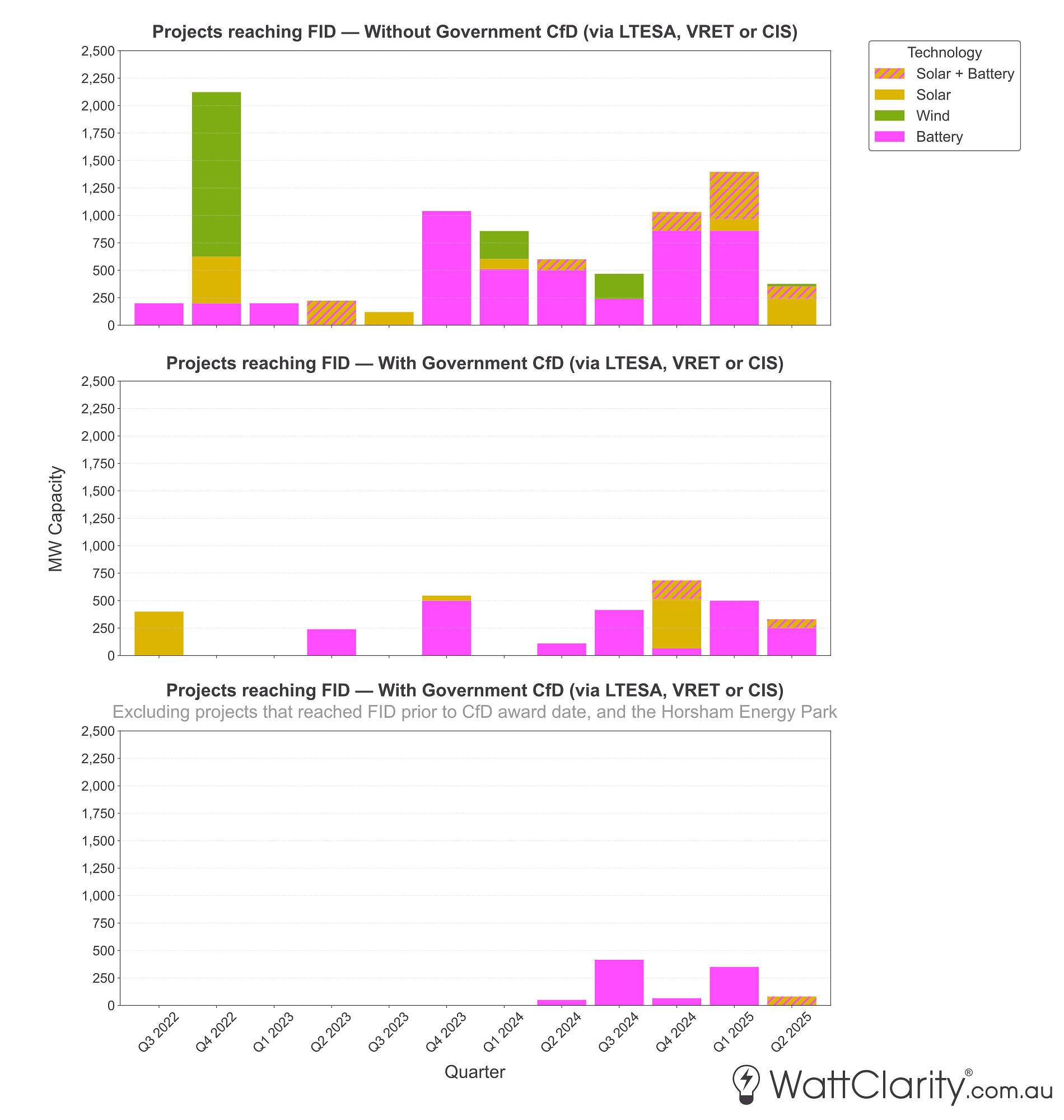

As a quick recap, in Part 4 of the series we shared a set of charts (reproduced below) showing the mix of projects that have reached FID since July 2022 — with and without government underwriting (via CIS, LTESA or VRET), which demonstrate:

- Batteries dominate new capacity reaching FID, irrespective of whether they have government underwriting or not.

- Relatively few wind projects have reached FID in the past 2.5 years, and none of them were underwritten via these government schemes. That absence of progress — with or without CIS support — likely reflects deeper challenges in the wind development pipeline, including rising costs, environmental approvals, and grid-connection delays.

- Some standalone solar projects are progressing, though a relatively large share have received government underwriting compared to other technologies.

Batteries dominate the projects getting to financial close over the past 2.5 years – with or without government underwriting.

However, when you exclude projects that had already achieved FID prior to winning a government contract, the picture becomes clearer: almost all of the new capacity progressing past financial close post-government contract award is battery capacity.

Once you exclude projects that had already achieved FID prior to their contract award, we see that it’s almost entirely battery capacity that has progressed to financial close.

Against that backdrop, it’s worth considering how having a CIS contract itself shapes a project’s contracting options.

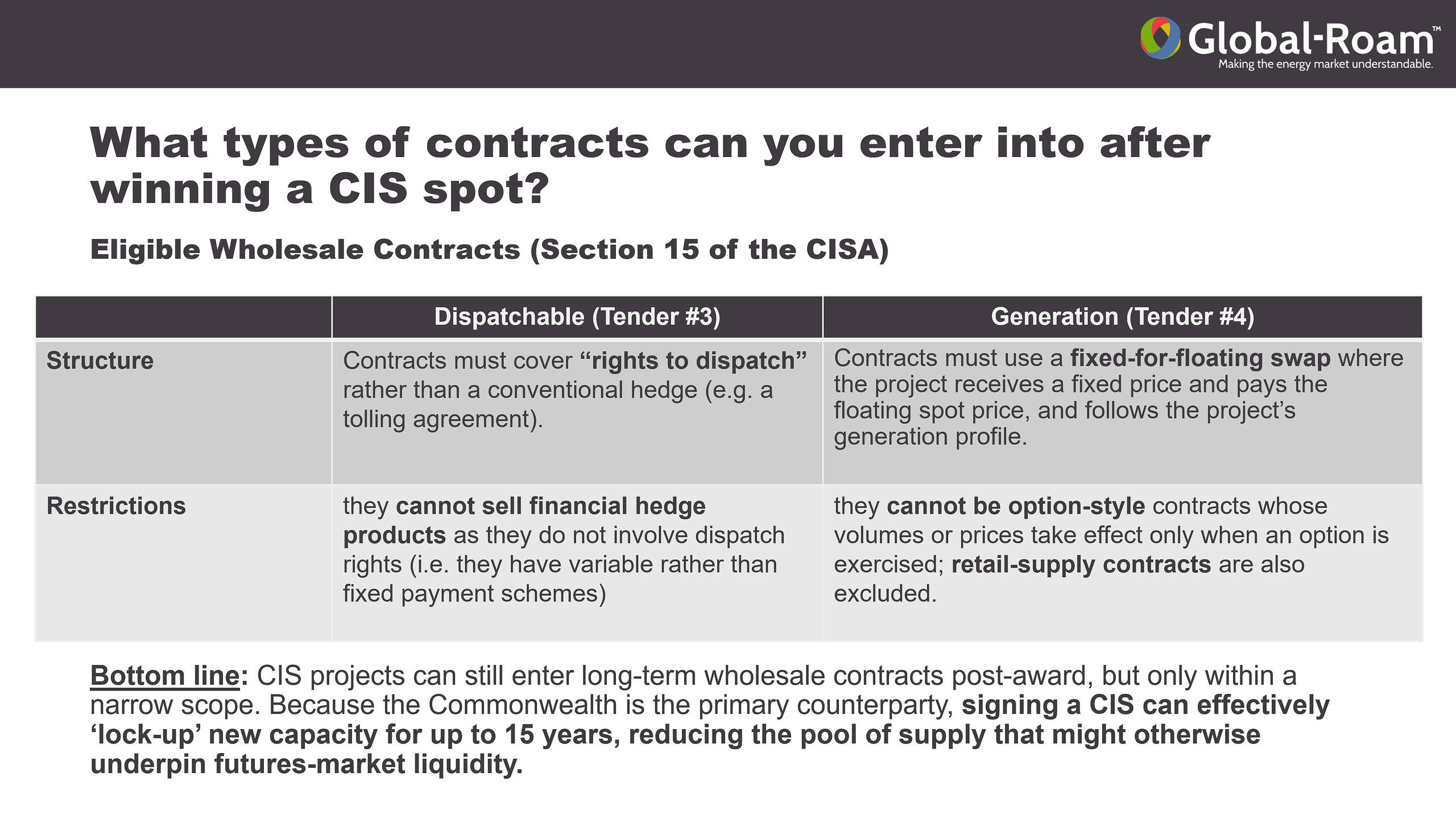

Eligible wholesale contracting for CIS projects

In this slide from our presentation on Wednesday, we summarised the key elements of Section 15 of the CIS Agreement (CISA) to clarify what types of wholesale contracting arrangements are permitted after a project wins a CIS contract. In practice, the CISA restricts proponents largely to tolling-style arrangements or fixed-for-floating swap–style arrangements. These constraints mean that projects may be more limited in how they participate in, and support, the broader contract market.

We consider this an important feature, especially for dispatchable projects, because these permitted contract types do not generally create or recycle the kinds of standardised, tradeable hedges that underpin liquidity in the ASX or OTC markets. This is particularly relevant for batteries. Although they are expected to become the main source of dispatchable capacity in the physical market as the coal fleet retires, the CIS framework prevents them from becoming a like-for-like replacement in the financial market. In practice, they cannot provide the same suite of hedge products that the coal fleet has historically supplied.

One audience member rightly pointed out to us on Wednesday that a tolling arrangement for a battery can still indirectly support liquidity, since the buyer of the toll is unlikely to leave their resulting exposure unhedged — unless they already hold a physical short position. This is correct; however there is a slight distinction, as any subsequent hedging is typically executed outside the transparency of the standardised futures market where it can be easily be recycled and re-traded. As a result, the liquidity benefit is diminshed and less visible to the wider market.

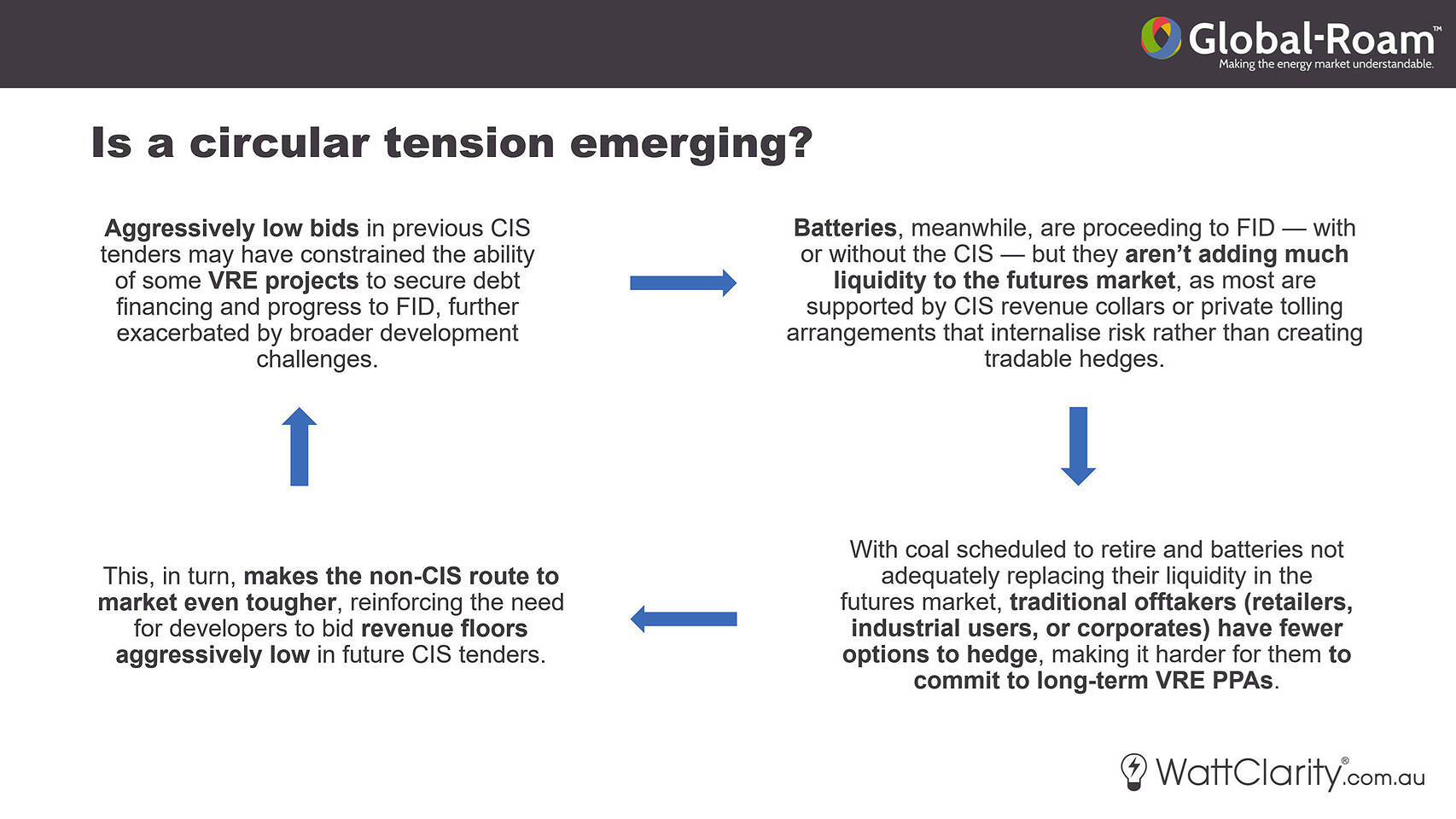

Is a circular tension emerging?

One of the final slides in our presentation posed a question about whether a feedback loop may be forming between CIS bidding behaviour, the contracting of batteries, and the liquidity needs of offtakers. The idea — framed only as a hypothesis — can be summarised as follows:

-

As discussed in Part 2 of our article series, several commentators have publicly suggested that some CIS revenue-floor bids in early tenders may have been pitched too low, potentially making it difficult for a number of VRE projects to secure debt financing.

-

Batteries are continuing to reach FID (both with and without government contracts), yet many are bound by CIS revenue collars (and/or private virtual tolls) that typically do not create or recycle tradable hedge products — meaning their contribution to contract-market liquidity is limited.

-

With coal retiring, and batteries not supplying equivalent hedge volumes, traditional offtakers (retailers, corporates, industrial loads) may be facing fewer options to hedge, making it more challenging to underwrite VRE through long-term PPAs.

-

This makes the non-CIS route to market harder, potentially strengthening the incentive for developers to bid aggressively in future rounds — thereby setting up the possibility of a circular tension.

We are not presenting this as a firm conclusion — but we’ve seen elements of those four tensions raised by different stakeholders independently, so it may be worth monitoring closely as the CIS scales up.

Other questions we continue to ponder

Below are a number of questions we continue to reflect on — either stemming from this analysis, or raised to us by stakeholders in recent conversations:

- Were revenue-floor bids in early CIS tenders, in fact, too low to support debt financing for many VRE projects — or is the slower progress more attributable to external development challenges such as environmental approvals, grid-connection delays, and rising costs?

- Has the CIS been additive? In particular, how many of the projects that secured a CISA and have since reached FID would likely have proceeded regardless?

- Would a (high) bid bond during the auction process have reduced the risk of speculative bidding or improved bid discipline?

- What is the cost to the development industry — in consulting fees, internal effort and time — of participating in these schemes, especially when only ~1 in 10 registrations in each round ultimately succeed?

- Would a battery covered solely by a CISA retain a strong enough incentive to respond to spot-market price signals? For example, if a project is operating under a limited cycle warranty, how strong is the commercial motivation to discharge if there appears to be little likelihood its total revenue would exceed their CISA floor.

- Will there be any constructed CIS projects that won’t privately contract after their CIS award? or does the scheme’s design adequately incentivisie particpants to set their floor at debt-financing levels, and hence still need to privately contract to get their desired rate of return?

- More broadly, how might revenue-collar arrangements influence real-time operational behaviour in ways that differ from assets with more merchant exposure?

None of these questions have simple or straightforward answers, given the complexity of the commercial arrangements and many unknowable counterfactuals. But given the scale of the scheme and its planned role in the transition, we think these questions are worth examining.

Looking towards the Nelson Review finale

Many of the questions raised above — and throughout our earlier analysis — intersect closely with the issues examined, articulated and addressed in the ongoing Nelson Review. The draft report touched on several of these themes, including market liquidity, contracting timeframes, the role of underwriting schemes, etc. We look forward to the release of the final report in December, and to seeing how its final recommendations may inform the ongoing evolution of market design more broadly.

Be the first to comment on "Reflections from our presentation to the CEC this week: A stocktake on the CIS"