Rio Tinto’s indication that Gladstone Power Station (GPS) could close in 2029, six years earlier than previously anticipated, has triggered widespread commentary. Much of the mainstream coverage has framed this as another milestone in the coal-to-renewables transition. That’s a transition we must have.

The situation, however, highlights something more fundamental: the National Electricity Market (NEM) is failing in a new way. This failure is not simply about coal plant economics, but about distorted market signals, misplaced risk allocation, and the lack of coordinated and timely planning.

The timing is significant. Queensland is about to release its Energy Roadmap 2025 tomorrow, promising to deliver “affordable, reliable and sustainable” energy through large-scale infrastructure projects such as pumped hydro (we hope), Wivenhoe upgrades, more gas and CopperString transmission. The roadmap is being framed as a practical response to transition risks. Yet Gladstone’s position shows how commercial exit decisions, poor planning, red tape, laws of physics and interstate interventions can undermine state-level plans that don’t consider pragmatics.

Gladstone in Context

Gladstone (1,680 MW) is Queensland’s largest coal-fired power station, supplying the Boyne aluminium smelter. The Boyne contract expires in 2029, and Rio has linked Gladstone’s future to this date.

Although described as “early closure,” Gladstone has already been operating at minimum stable load (Pmin) almost daily for the past year. In effect, the plant is already mothballed.

Ownership of Gladstone is also complex. Rio Tinto holds just over 42%, US-based NRG Energy owns 37.5%, and the remainder is held by Japanese investors. This shared structure blurs accountability for the plant’s future. No single owner is responsible for ensuring Gladstone remains viable, yet governments bear the consequences if its closure undermines system reliability, which is keeping the lights on.

Why Eraring Matters to Gladstone

Gladstone’s situation is directly linked to developments at Eraring Power Station in New South Wales.

- Eraring’s extension was driven primarily by the need for system strength and inertia, not energy pricing, supply or system constraints.

- The synchronous condensers intended to provide these services are delayed, mostly due to regulatory inertia. A Rule change sought in 2020 moved quickly to provide new powers for TNSPs to manage system strength, but no process reform to deliver those capabilities rapidly.

In its Rule change proposal Transgrid noted (p. 6 here):

“More generally, none of these [current] processes represents an appropriate avenue to quickly implement changes to improve the management of system strength on the power system. This rule change proposal is required as a matter of some urgency to address the rapidly emerging issues with the current framework.”

And that (p.15):

“It is likely that some system strength needs will arise rapidly … In these circumstances it is likely that an alternative and shorter cost-benefit analysis process would be appropriate.”.

The AEMC ignored Transgrid’s request for a new cost-benefit process and retained the ~ two+-year RIT-T process, a process with appeals. When it comes to physics, sometimes the solution is but one. When it comes to the removal of fault-current due to the exit of coal, at this point in time, that can only be replaced by other spinning machines.

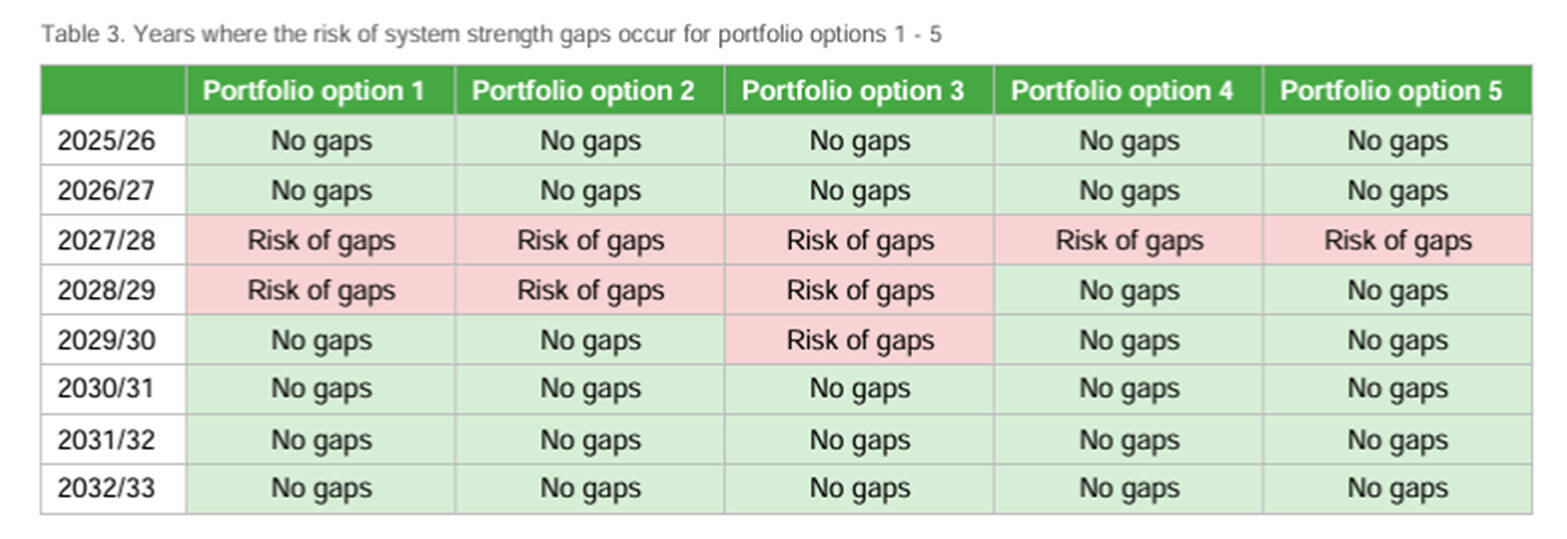

So here we are at the end of 2025, Transgrid is still navigating the RIT-T process and cannot order syncons that are clearly needed. And so, they are unable to commit to having them ready pre-2029. Transgrid notes this clearly in their summary table (below) in their RIT-T final report (p. 8 here). The risk of system strength gaps remain in NSW because Transgrid has spent years navigating process to buy some kit every first-year electrical engineering student knows we need to replace Eraring.

The outcome is Transgrid saying on page 1 of that report:

“A network without adequate system strength will result in stability issues and supply interruptions to end consumers”.

This has created a chain reaction:

- NSW extends Eraring to address system security shortfalls.

- That decision suppresses revenues for Queensland coal units.

- Gladstone Power Station’s economic case weakens further years before its nominal end date.

- AEMO’s Feb 2025 system strength report (p.25 here) found 3 new system strength shortages in Queensland, including one near Gladstone, are “primarily linked” to Eraring staying open longer.

And ultimately, we all then expect Eraring will be extended again to 2029. When you are in a system, whole-of-system thinking adds all this up to more.

Incentives and Strategic Behaviour

Reports are Rio has secured renewable supply contracts covering approximately 80% of Boyne’s post-2029 energy requirements, but only about 30% of firming. This leaves deliberate space for negotiation.

The result is a credible position that firming can be sourced more cheaply elsewhere, while leaving the option open for government to provide support if Gladstone is required for system security. And, to enable a longer economic and people transition for Gladstone. That power station has been the bedrock of that community for half a century. And they’ve just been told it is likely going to close 6 years early.

The reason for that is current incentives encourage exit signals as bargaining tools rather than aligning long-term system needs with commercial decisions.

The Role of State-Level Plans

Queensland’s forthcoming Energy Roadmap highlights the state’s determination to ensure security through major investments in pumped hydro (we hope), more gas and transmission.

The challenge is sequencing. Most of the Roadmap’s projects will not be fully operational until after 2028–29 – the same period AEMO has identified as a critical reliability pinch point if Gladstone exits.

This raises the question: do such plans resolve the underlying design flaw, or do they simply shift political risk? Governments can reassure voters with announcements, but the NEM still lacks mechanisms to align commercial closure timelines with the readiness of replacement capability, and critically, the risk responsibility to deliver it

A Whole New Kind of NEM Failure

Gladstone illustrates a structural weakness in the NEM that extends beyond coal economics:

- Risk allocation mismatch

- The NEM does not allocate responsibility for system security to those ultimately accountable – governments.

- When blackouts occur, governments face the political consequences, yet the framework gives them limited levers to manage an orderly exit.

- The complicated ownership structures at Gladstone, and other market participants, adds to this mismatch. With decisions shaped by a mix of global shareholders, accountability for security is externalised and distributed, while actual responsibility falls on state and federal governments.

- Interstate knock-on effects

- A government intervention in one state (Eraring’s extension, NSW) reshapes plant economics, and the future of an entire community, in another (Gladstone, Queensland).

- State roadmaps, including Queensland’s new plan, need to manage political accountability and correct these cross-border distortions.

Conclusion

Gladstone’s prospective closure has been widely presented as another step in the energy transition. We must exit fossil fuels, but that exit needs to avoid candles. Blackouts risk lives, they cost millions, they are not just an inconvenience. In reality, it reveals that the NEM is failing in a new way.

It demonstrates that:

- Market signals are incomplete and distorted by interventions.

- System risk and accountability sit with governments rather than companies.

- State-level interventions and ownership complexities reverberate unpredictably across the NEM.

Queensland’s Energy Roadmap may help by de-risking the future through pumped hydro, more gas (if this is possible in time, but that’s another story) and transmission projects, but its timelines collide with the short-term risks to operation of the power system, and the ongoing impacts of these market arrangements.

Unless market design is adapted to properly value and coordinate the planning and timely investment in essential system services, unless we start to rapidly connect generators like they are rooftop PV, and unless we align risks with responsibility; coal exits like Gladstone coupled with looming gas planning and supply shortages will continue to unfold and impact in ways that are unmanaged, chaotic, and politically fraught.

As the great Charlie Munger once said, Show me the incentive, and I’ll show you the outcome.

About our Guest Author

|

Greg Elkins is the CEO of Global Power Energy. Previously he worked at Energy Queensland and within AEMO to facilitate the transition of the energy mix to renewable technologies including wind, solar and battery by managing technical teams to look at new ways of doing things and to test the boundaries. His forte is in the provision of strategic technical advice within the energy industry. |

Good thoughts, but it may be even knottier. Rio needs Gladstone PTI committed to close GPS while Powerlink need a GPS retirement date before 2030 to justify Gladstone PTI. So in a way, GPS is forced to announce retirement before that retirement is feasible if they want any chance of the retirement becoming feasible later.

I think the early closure of Gladstone has been speculated for many years. The author doesn’t even mention the subsidy the station receives via CS Energy. Nor do I personally think system strength was the major reason for the Eraring extension. And although the firming for Boyne Island is not yet known I suspect QLD plans to build a new gas plant and that coal from other plants will provide the firming while it’s being built. That’s not a solution I favour but what do I know.

Its getting hard to ignore the rollout of batteries even for the most conservative of “experts”, but what is clear is we are still in the high growth phase so forecasting where we will end up is little more than a guess, and then you have to reestimate what power and energy looks like in such a system.

An excellent article. Thanks. Interesting how one state government actions can change plans somewhere else on the eastern seaboard.

The inbuilt conflict between government’s ultimate responsibility to maintain power supplies and the commercial decisions of companies and investors on the timing of closing aging power plants was, in the case of NSW, created by the very government having privatized what was and should have remained public infrastructure in the 1st place. With this privatization, the State government wanted to rid itself of the difficult transition away from coal. This opportunistic approach has backfired.

Great article. The Author could include some other points or solutions. Most coal power plants in Queensland are Government owned so I don’t think this will be a systemic/repeat issue. Other solutions could include: (1) other Queensland coal power plants can have their life extended, or alternatively (2) another coal plant could close instead to improve the economics/operation of Gladstone.

Thanks for the article. It was interesting to read the following statement, “Gladstone has already been operating at minimum stable load (Pmin) almost daily for the past year. In effect, the plant is already mothballed.”

There is nothing unusual about a unit at GPS running at “Pmin”. Historically this may have been after evening peak demand. It also was dependent on which units on line were contractually supplying Boyne Smelters. The other units would at, or be close to, Pmin. The change is that this Pmin period has shifted and extended each day.

Regarding reliability, it should be noted that reliability of a power station depends on the resources available, including reasonable continuous funding for maintenance, asset refurbishment/replacement and associated periodic shutdowns. Since privatisation, GPSGOS (Gladstone Operating Services) has had a funding model based on reliability, not MWe (export). This funding was fixed and eroded dependent on having the contractually agreed number of units on line. This can be a challenging environment when operating a coal fired power station that has been operating since the 70’s. Particularly when you don’t have control over the quality of coal you need to burn.