This article is the fourth and final instalment of our series exploring the federal government’s Capacity Investment Scheme (CIS) — what it set out to achieve when it was announced nearly three years ago, and the early results since then.

To quickly recap the first three parts of this series:

- In Part 1, we examined the progress of CIS-backed projects since their contract awards, showing that only a small number of projects from the earlier tender rounds have reached the ‘committed’ phase, and discussed the impacts of that effect on the AEMO’s long-term modelling.

- In Part 2, we unpacked some of the delivery bottlenecks — including suggestions that the competitiveness of the tender rounds pushed participants to bid at unsustainably low levels, along with the limited alternative pathways to market and other development constraints and external pressures facing projects.

- And in Part 3, we examined how curtailment risk is treated (or not treated) under the CIS, and some of the confusion caused by an earlier draft of the CIS agreement.

In this fourth and final part, we zoom out to look at government-orchestrated contract-for-difference auction schemes more broadly. Drawing on recent insights and findings from the draft Nelson Review, we explore what government CfDs might actually be doing for (and to) the market — and whether policy enthusiasm for these attempted ‘exit before entry’ interventions risk running ahead of the problem they’re meant to fix.

CfD auctions: All the cool governments are doing it

Government-orchestrated CfD auctions were popularised in European power markets in the 2010s, and have become all the rage in the NEM in recent years.

A Contract for Difference (CfD) is a long-term agreement that guarantees a fixed “strike price” for a project’s output — under a two-way CfD, the offtaker pays the asset owner when market prices fall below that level and receives payments back when prices rise above it. The goal is to provide revenue certainty and reduce investment risk. The CIS differs slightly from a traditional CfD by using collars — a revenue floor and ceiling — instead of a single strike price.

Across the NEM, government-backed CfDs have been delivered through competitive auctions: effectively, developers bid their lowest possible strike price to minimise the amount of risk in public hands (as the government acts as the offtaker). In recent years, these auctions have become the policy tool du jour — from the Commonwealth’s CIS, to New South Wales’ LTESA, Victoria’s VRET auctions, and South Australia’s new (and rather cool-sounding) FERM scheme. The design of these schemes and the underlying derivative/option structure differ slightly in design, but all use similar mechanics, aimed at underwriting downside risk of new capacity in order to bring them online before existing thermal generation retires.

They’ve proven rather popular. Developers like them because their large headline targets offer hope for projects to reach final investment decision (FID), they signal strong political commitment, and promise long-term revenue stability. Governments, in turn, favour CfDs because they minimise upfront fiscal outlay: rather than paying direct grants or subsidies, payments only flow when market prices are low — and in some cases reverse when prices are high.

This creates the appearance of a self-balancing scheme, which makes it easier for Treasuries to justify, since the net cost over time can be lower than other interventions. CfD schemes also give governments a perception of control over market outcomes — a way to steer investment toward their capacity and emissions commitments without heavy public spending or a return to full-blown central planning.

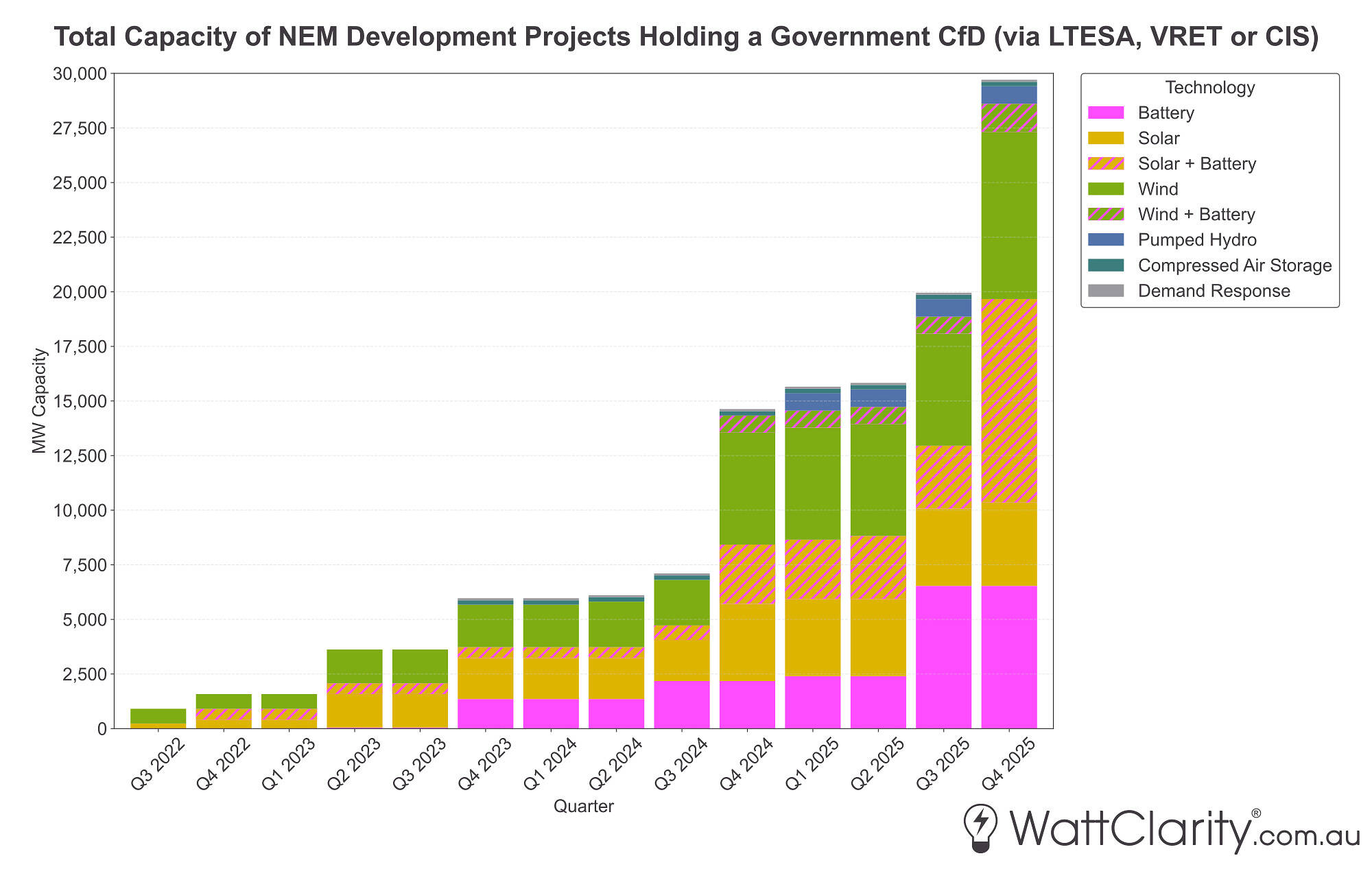

As of today, almost 30 GW of development projects have been underwritten by a Government CfD via the CIS, LTESA or VRET auctions.

Note: For hybrid projects, the total capacity of all components is shown. If you spot any errors, please let us know.

Source: AEMO Services, Victorian Government, ASL, DCCEEW

Are government CfDs delivering on delivery, yet?

In Part 1, we examined AEMO’s Generation Information dataset to understand the current commitment status of CIS projects — particularly to explore what that means for how “firm” the awarded capacity really is in planning and modelling contexts.

In this follow-up, we broaden the lens. Using several editions of the Clean Energy Council’s Quarterly Investment Reports, we’ve scraped and consolidated data on projects reaching FID, attempted to clean up and fill in any gaps in their reporting by checking company announcements, and cross-checked it against the official LTESA, VRET, and CIS award lists.

What’s actually reaching FID, with or without government auctions

Simon Vanderzalm from Greenview Strategic Consulting recently made a great point on LinkedIn — Victoria’s VRET 2 auction stands as an early cautionary example of how government auctions have struggled to translate into real-world delivery. Of the six solar farms awarded contracts in that auction in 2022, three have yet to start construction or reach FID more than three years later. And of the three that have, one (the Horsham Energy Park) only advanced to FID after being bought out by Victoria’s State Electricity Commission — another entity within the same government that underwrote the project in the first place.

We’ve also seen another curious outcome in recent CIS tenders — with several winning projects already constructed or at financial close, prior to winning a contract, as RenewEconomy recently noted. This was by design: policy-makers were keen not to stall the development pipeline while tenders were being assessed, so allowed (or even encouraged) such projects to participate in auctions. Still, it raises an interesting question about whether the scheme is accelerating new investment, or simply underwriting projects that were likely to proceed anyway.

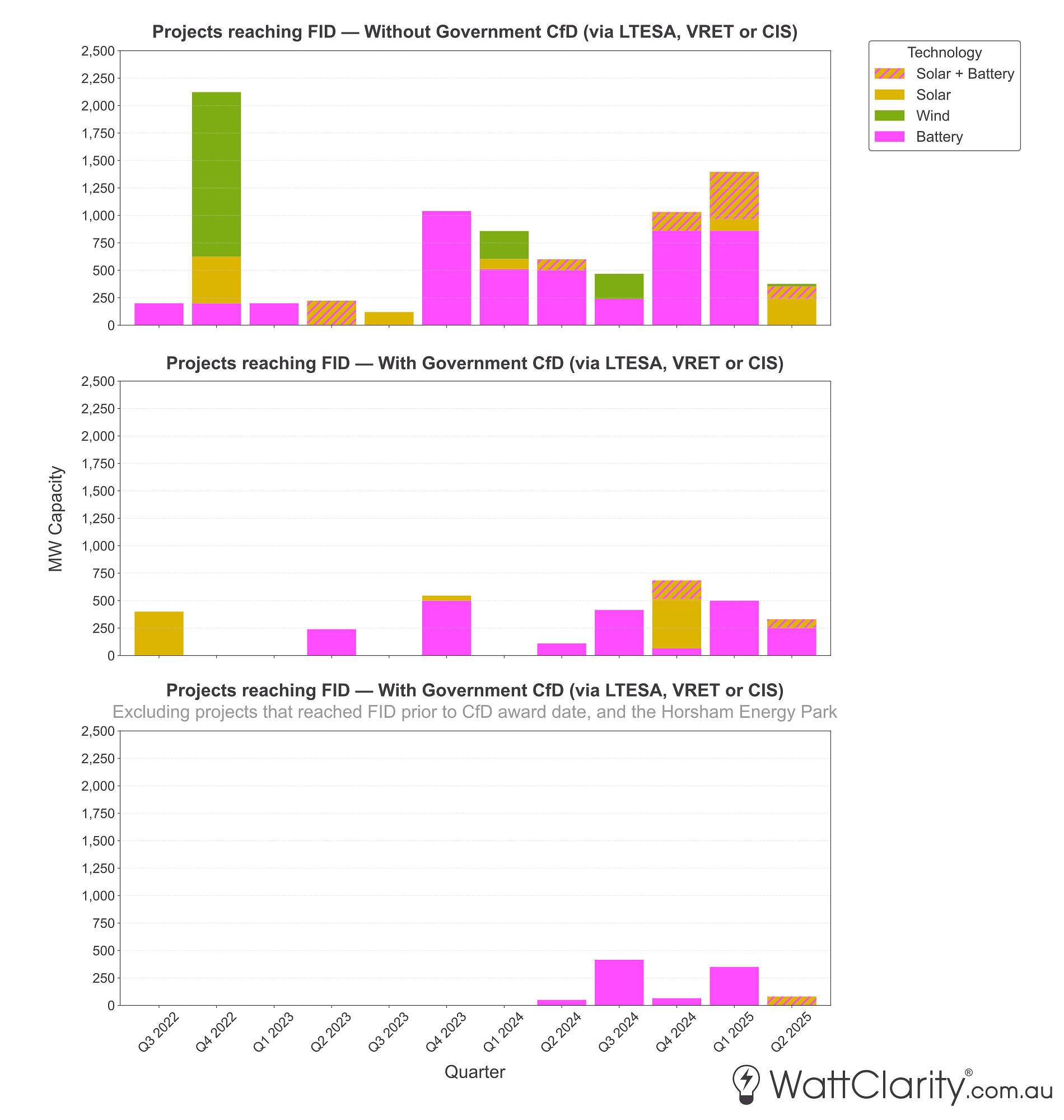

The figure below combines all our collated data sources to show how projects have progressed since mid-2022 — distinguishing between those that reached FID with and without government-backed CfDs. The bottom panel further filters the results to exclude projects that had already reached FID before their government award (and the Horsham Energy Park), helping to isolate FID decisions most directly attributable to the schemes themselves.

Since mid-2022, only a limited number of projects from earlier government CfD auctions have reached financial close once you exclude those that had already reached FID pre-award.

Note: Where the FID data was not made public, but major construction works began, the construction commencement date was selected. For hybrid projects, the total capacity of all components is shown. Only projects greater than 20MW shown. If you spot any errors, please let us know.

Source: Clean Energy Council, Victorian Government, ASL, DCCEEW, Company Announcements

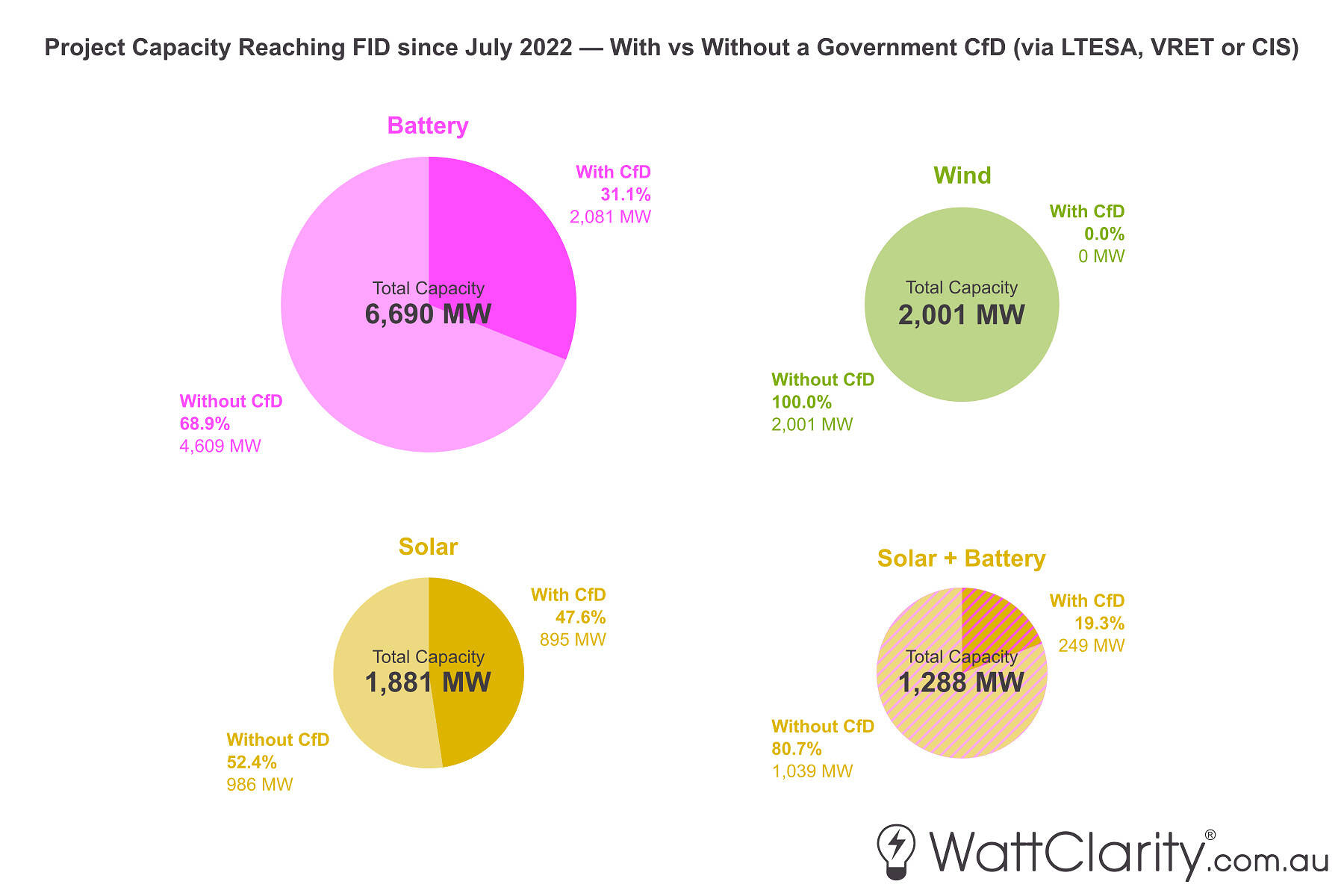

As the charts show, only a small portion of the projects participating in the tenders have reached FID since being awarded their contracts. And among those that have, most are battery or solar-battery hybrids — the same project types that are also proceeding without government support. This demonstrates that batteries are driving much of the current investment momentum in the market, regardless of whether they have government support.

Of course, it’s still early days. As seen in the first chart of this article, government underwriting activity only began to scale up rapidly around 12 months ago, so a longer lead time to see the full trend might be needed. However, it’s also worth exploring the potential for crowding-out effects.

Government underwriting can “sterilise” capacity that might otherwise have been available to support the contract market — a theme we unpacked in Part 2 of this series. When a project secures a government-backed CfD, its contracted volume is effectively removed from the pool of generation that could be offered to private offtakers (e.g. large energy users or retailers) through other hedge arrangements. This reduces overall liquidity in the contract market and can make it harder for those private counterparties to secure firm, long-term hedges to back new projects that don’t receive government support.

As I noted in Part 2, oversubscription in recent CIS tender rounds has meant that roughly nine out of ten projects that register for each round are ultimately unsuccessful — if unsuccessful, those projects must then compete in a thinner contract market, where a growing amount of dispatchable capacity is sterilised by public underwriting. The effect of this on generation projects in particular is that their potential offtake partners have less options to hedge, and hence are less willing to sign long-term contracts.

Battery projects dominate FID activity — both with and without CfDs — but their heavy representation in government auctions raises questions about whether public underwriting is “sterilising” capacity that might otherwise support private offtake deals.

Note: For hybrid projects, the total capacity of all components is shown. Only projects > 20 MW included. If you spot any errors, please let us know.

Source: Clean Energy Council, Victorian Government, ASL, DCCEEW, Company Announcements

Since July 2022, about one-third of all battery capacity reaching FID has been tied to a government CfD.

Wind, on the other hand, has seen no government CfD-backed projects reach FID during our 3+ year sample period, which is likely reflective of deeper issues affecting the wind development industry such as environment approval issues, rising turbine costs, and other factors — problems that government underwriting alone can’t fix.

We also see that governments are also underwriting a large share of standalone solar (47.6% of all such projects reaching FID). If we were to include the 240 MW PPA of Wandoan South Solar Farm Stage 2 with the Queensland’s government-owned CleanCo, more than 60% of new solar capacity in the past 2 and a half years is now publicly backed — suggesting that governments are steering more investment towards standalone utility solar than the market is signalling.

Reading between the lines of the Nelson Review

The Nelson Review panel spent several months earlier this year on a listening tour of the NEM — running their own consultations, analysis and drafting a candid assessment of Australia’s investment framework. In the draft report, released in August, the panel neatly articulates several structural challenges at the heart of this debate. On page 11, the report highlights their core finding.

“The first and most persistent of the barriers to new investment is the ‘tenor gap’: a mismatch between the long-term contracts needed by sellers to finance capital-intensive assets (often 10 to 30 years) and the short-term contracting of buyers (typically three to seven years). … Policy frameworks must strive to provide as much stability and predictability as possible.”

This is exactly the problem that the CIS and similar schemes were designed to address. Yet, as this series has shown, underwriting doesn’t always translate to delivery. These contracts may bridge the tenor gap on paper, but their design and implementation can also create unintended consequences. On page 10, the panel calls this out.

“While direct government interventions, such as the CIS, have provided revenue certainty for new investments, they typically do not contribute to derivatives market liquidity. Instead, they operate in parallel to the market, potentially crowding out private hedging activity and limiting the development of deeper, more transparent financial markets.”

Later, on page 12, the report turns to a broader concern about sequencing and timing in the transition, and focusing on policies that actually deliver what the market/energy system needs.

“The second barrier to new investment is uncertainties driven by policies to achieve entry before exit.… Unless policies achieve timely delivery of bulk energy, shaping, firming and the requisite system services … they risk creating a vicious cycle: uncertainty discourages investment, delays new entry and triggers further ad hoc interventions, exacerbating the very problem they aim to solve.”

Key Takeaways

With around 30 GW of projects now underwritten through government CfD auctions — and more tender rounds still ahead — it’s important for the industry to continually take stock of how these schemes are actually working in practice.

Ultimately, their success will depend less on how many contracts are signed, and more on how many projects actually get built that wouldn’t have proceeded otherwise — and whether those projects help close the gap they were designed to fill.

After four articles and several thousand words of analysis, a few takeaways to finish:

- Good intentions aren’t enough. Underwriting schemes like the CIS were designed to de-risk investment, but delivery challenges show that policy ambition alone doesn’t guarantee new capacity on the ground.

- Policy needs to be additive. Government CfDs should complement — not crowd out — private contracting and market signals, helping expand the overall investment envelope rather than reshuffling it. CfDs now cover such a large slice of the development pipeline that they risk overwriting, not just underwriting, market signals.

- Success should be measured by outcomes, not announcements. What matters is how many projects are actually built, and whether they help us move closer to an orderly exit of existing coal generation.

Leave a comment