Yesterday on WattClarity, I contributed ‘Some thoughts (part 1) about the design paper for the implementation of the proposed Capacity Incentive Scheme’. In this article (part 2), I will discuss some details of its design that are open for consultation until Monday next week, 25th March 2024.

As discussed in Part 1, the CIS has two forms of 15-year Capacity Investment Scheme Agreements (CISAs), Generation (for variable renewable energy) and Clean Dispatchable (for non-emitting dispatchable capacity, principally batteries). They each use a revenue collar and are conceptually similar, but also with necessary differences.

The Paper discusses them at times collectively and sometimes separately. Below they are discussed collectively, with differences called out.

The Collar concept

Unlike a Contract for Difference (CfD), which settles every trading interval against market price and generation volume, revenue instruments are measured over time and take more cashflows into account. It is hoped the owner will operate as if it were a market exposed business, which, when operating between the ceiling and floor, it truly is. Meanwhile, by agreeing to share the extremities of the ranges of profit with government, the project is more bankable up front than were it entirely operating to market. But when operating at or near these extremes, incentives on the business will alter in undesirable ways, and the CISAs have features to combat this.

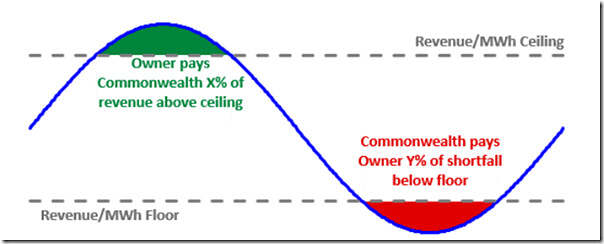

In the Implementation Design Paper these structures are illustrated as follows – note the key difference, which is explained further below:

| For the Variable Renewable Energy (VRE)

… which in the language of the CIS is ‘Generation’ |

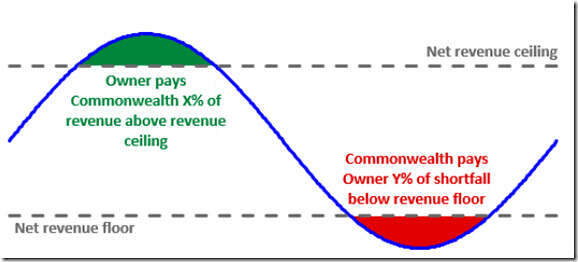

For the Firming Capacity

… which in the language of the CIS is ‘Clean Dispatchable’ capacity |

|---|---|

|

Figure 1 Revenue collar for Generation CISA Source: Implementation Design Paper |

Figure 2 Revenue collar for Clean Dispatchable CISAs Source: Implementation Design Paper |

|

For a Generation CISA, the collar is defined as “net revenue per MWh of generation”, i.e. the revenue is divided by actual generation (at the regional reference node). This unit is shown in figure 1. It has the result of:

If revenue is down, because, say, there has been a wind drought, rather than weak prices, the asset will not be supported. |

In contrast, the Clean Dispatchable CISAs apply to the assets entire revenue without dividing by generation, and the collar is simply triggered by total dollars earned.

This is aligned with both:

|

The floor and cap triggers are bid by the proponent at auction. The lower the triggers are offered per equivalent unit of capacity, the more likely it will be selected. The triggers may progressively escalate.

Ceiling and floor payments are made quarterly, but then trued up at the end of a financial year, so effectively the green and red revenues above should be thought of as measured and applying over a year.

The ceilings and floors intentionally don’t make the asset fully whole. A degree of market exposure is retained by the owner to incentivise performance. The proposed sharing, subject to consultation, is that the government covers 90% of the difference between actual revenue and the floor, and that 50% of any revenue above the cap should be handed over, up to an “annual payment cap” that is also bid in the tender.

Assets must be owned by a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) rather than embedded within an integrated portfolio. This is because the revenue collar requires the asset to operate and be accounted independently. If it were part of a portfolio, there is a natural incentive to operate or account it such that the CIS asset’s revenue is artificially depressed in favour of other assets.

The SPV should enable transparent accounting around the asset, and there are rules and monitoring around contracts with related parties. However, it is difficult to devise any structure that can confidently be said to operate fully independently.

What is revenue?

The collar triggers on “net revenue”, which is not straightforward. In broad terms, it is the net revenue result of operating in spot and contract markets, i.e. pool revenue, plus green credits, plus or minus contract transactions, minus pool charges. All other operating costs are excluded.

The government wants CISA assets to contract their output, and the settlement of those contracts does count towards the revenue collar. Because this invites contracts designed to transfer revenue elsewhere, a concept of “Eligible Wholesale Contracts” can disallow contracts if they are seen to be for the purpose of changing CISA payments.

Whilst the checks on contracting seem appropriate against intentional gaming, it seems unavoidable that the mere presence of the floor would encourage greater risk taking when selling contracts than if it weren’t there.

Generation CISAs (i.e. for Wind and Large Solar)

Here’s Figure 1 again:

For a Generation CISA, the collar is defined as “net revenue per MWh of generation”, i.e. the revenue is divided by actual generation (at the regional reference node). This unit is shown in figure 1. It has the result of protecting against adverse market conditions, but not poor physical performance. If revenue is down, because, say, there has been a wind drought, rather than weak prices, the asset will not be supported.

This is to encourage the renewable generator to maximise generation where it can. Revenue divided by generation has the same unit as price, and although it is not strictly that, the collar triggers could be broadly described as “the volume weighted average price” of that generator across a year.

Some significant matters where the generation collar intentionally does not protect assets are:

- Negative prices. Spot market payouts due to running during negative prices does not subtract as a negative revenue. This is necessary, as to leave in the scheme an incentive to maintain output during periods of excess renewable supply would be very costly and create a power system security issue. Like all renewable investors, an expectation of negative prices correlating with output remains a serious consideration to bidders. Calculating the “volume weighted average price” discussed above first requires truncating all negative prices to zero.

- Congestion, connection delays and security constraints. Because revenue is divided by output, declines in revenue due to such curtailments is worn by the investor. Again, this is necessary to encourage the investor to locate and operate in a way that minimises these risks.

- Loss factors. By applying the current loss factors to the denominator, a decline in revenue due to an unfavourable movement in loss factors is not protected.

Generation CISA variants

The Paper seeks input on whether to offer two variants to the Generation CISA, each of which would remove the necessity of a SPV.

The first variant is to model the NSW Roadmap “option” design where instead of an ongoing revenue collar, an operator has the right to exercise an option when business conditions prove unfavourable. Upon exercise, a one-year CFD applies to any generation not already subject to an eligible contract and the transfer of all green certificates to government. It also invokes a revenue sharing cap for the rest of the life of the CISA.

The second variant applies the collar only to the spot revenue coming from the proportion of generation not spoken for by a sold eligible contract. If an operator has sold contracts equivalent to half of its capacity, then the revenue coming from the spot exposed half would be divided by half the total output to determine the net revenue per MWh of generation for triggering the collar.

Clean Dispatchable CISAs (i.e. for Firming Capacity – but not fossil fuelled)

These CISAs apply to the assets entire revenue without dividing by generation, and the collar is simply triggered by total dollars earned. Here’s Figure 2 again:

Like Generation CISAs, revenue includes spot income (including ancillary services), minus the cost of charging and other pool costs, plus or minus eligible contract transactions, plus any green (if eligible) or (possibly in future) capacity payment income.

Delivery and Performance

The CISA’s design means that the assets can mostly be left on their own to perform in response to market incentives, but there are a few obligations.

Successful projects must commit to a commercial operation date as a contracted milestone. Bidders are likely to have to submit a bond, to inhibit non-serious bids. The bond is not discussed in the Paper, but in a public forum the order of a few hundred thousand dollars was mentioned.

Generation CISAs will be subject to a minimum generation requirement to encourage high availability. The Paper suggests by example at least 75 percent of the 90 percent probability of exceedance (PoE) generation but does not discuss how that threshold is determined nor whether there are exemptions for negative prices, congestion and system limits.

Clean Dispatchable CISAs will be required to have a tested capacity at least what it bid in the auction (it may include a degradation profile) and an ongoing availability over 90 percent.

As per the NSW Roadmap and Vic/SA tender at least 50 percent of the Clean Dispatchable capacity must be available to run during an actual Lack of Reserve (LOR3)event. This is apparently insisted upon by the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) and sits incongruously with the self-incentivised rest of the instrument.

1) Whilst it appears a minor constraint, it limits dispatch flexibility for a storage asset defending contracts.

2) Its emergence suggests misunderstanding of the way the market operates during an extended crisis such as June 2022.

As administrative pricing destroys incentives to store energy (which was described as Theory 2 in this article on WattClarity at the time), AEMO must already intervene by directing all energy-limited plants, not just CISA ones, which are kept whole by direction compensation. Thus, the constraint doesn’t appear to be of value to AEMO anyway.

Eligibility

Technology

Both CISAs are only available to scheduled or semi-scheduled capacity over 30MW that does not produce emissions.

Given recent trends, the Clean Dispatchable CIS will be dominated by large-scale batteries. There is no requirement to charge the batteries with renewable energy, a suggestion that was sensibly discarded in 2023.

Whilst not necessarily competitive, renewable-fuel plant is eligible, but not native forest waste.

Demand-Side Response (DSR) and Virtual Power Plants (VPPs) are not eligible in the first rounds, but the government proposes to consider them in future tenders.

The exclusions of non-scheduled plant, DSR and VPP are for understandable practical reasons as they would require bespoke administrative arrangements for relatively small returns. Whilst the government supports DSR and VPPs, each has difficulties in a scheme like the CIS in gaining confidence that government is paying for genuinely additional and firm capacity.

The most significant exclusion, peaking gas turbines, was an ideological decision made at ministerial level in 2022 and discussed in Part 1.

Readiness and Cutoff dates

To participate in a tender, the project would need to have at least arranged its land tenure and begun connection discussions. There will be aggressive delivery date requirements and as a result the government openly expects the CIS to favour mature technologies (wind, large-scale solar and large-scale batteries).

The CIS is intended to build new assets, but the cutoff date for getting AEMO committed status is not the time of the tender but instead the date of the original ministerial announcements of the two CISAs:

- 8 December 2022 for Clean Dispatchable (i.e. Firming) and

- 23 November 2023 for Generation (i.e. VRE).

Although this looks strange, it is necessary to avoid a perverse incentive to pause a project already underway.

Projects who were committed before the tender will face a difficult challenge in determining their bid parameters, as it will be based on their assessment of the competition rather than their own costs which are sunk.

- Being a “pay as bid” auction, they will either underbid and leave money on the table or overbid and miss out entirely.

- Common-clearing price auctions would be fairer but impossible due the way CIS tenders are assessed.

Storage Depth

The minimum storage depth is two hours, however the government is aware deeper storage is more valuable and notes the Vic-SA tender applied a four hour minimum. In the Western Australian Wholesale Electricity Market (WEM) Reserve Capacity Mechanism (RCM) a simple linear conversion has been used to normalise battery capacity by dividing the depth by 4 hours. The Paper however proposes that tendered capacity is compared instead by the effect it has in reducing Unserved Energy (USE) in probabilistic modelling. This is certainly more accurate and defensible but is less transparent.

Its not clear how different storage depths would be counted towards the 9GW target. It seems a simple normalisation might be used in this case.

Participation in other schemes

This section will entertain cynics. Eligible CIS projects may not receive other government support, but then the Paper lists as exceptions to this rule all conceivable forms of government support. The exceptions list even has a catch all, “Other forms…where the financial support is stipulated to be complementary to the CIS…”, which seems an invitation to states to top up their favoured projects with some extra pork.

Selection

Stage A

Like other schemes, the tender begins with an unpriced technical shortlisting. In stage A all structural details on the project are provided, demonstrating the credibility of the project and proponent. Importantly it provides technical information to determine the project’s system impact at the selection stage.

Stage A also requires subjective information about local content, worker conditions, community and First Nations consultation and end of life plans. Bidders will likely engage a communications advisory firm to prepare the sort of text that government likes to see.

Stage B

Those who pass Stage A submit their pricing bid variables in Stage B and required contract variations. They also back up the subjective information from Stage A into a “social licence commitment”, which presumably requires measurable specifics such as identifying local parts suppliers and how many apprentices will be taken on.

Assessment

Financial selection is not a simple comparison of bid prices but a complex modelling exercise. By feeding the project into a model, the expected exposure to government from the collar can be simulated. This is divided by the model’s estimate of, for Generation CISA, the renewable energy produced, and for Clean Dispatchable CISA, the avoided USE. The Clean Dispatchable selection will also investigate “broader system benefits”, presumably such as ancillary services. It will also consider the project’s ability to reduce market price.

The modelling approach, if done well, is perhaps as good as is possible for selecting such a tender. It will inherently favour forms of renewable energy that operates at times of greater system value and is less congested. It will also favour deeper storage, but only to the extent that the power system needs it given other sources and the expected length of renewable energy droughts. Technical matters like cycling losses will also be captured.

Including the ability to reduce market price is a questionable selection objective. Prices are notoriously difficult to model and depend on gross assumptions around future ownership structures, market power and contracting and bidding strategies. It is also doubtful that government should be trying to drive price anyway in its micro-decisions, which impacts other investors and the government’s own payments under the CIS. Fortunately, it seems likely that the priority order of projects from their modelled system benefits would be the same priority order as their modelled impact on price.

Merit selection will also consider the social licence commitment. These subjective matters may be politically necessary but endanger the appearance of fairness and probity, especially as local content and worker conditions introduce the potential for bias towards favoured business and unions.

Hybrid Projects

The Paper provides an option for a renewable energy generator with a battery at its connection point to bid as a hybrid project and will be classed as a Generation CISA.

The modelling described above should be able to capture the benefits deriving from the battery, e.g. generation can be somewhat better correlated to system need. It will require some more complexity in its bidding parameters. The paper seeks comment on that and whether some hybrid projects might be better classed as Clean Dispatchable CISA, and how this would be done.

Conclusion

Having made all the macro decisions at ministerial level, bureaucrats’ freedom in this design process is limited, but they have exercised it well. As far as a design for a scheme that uses a collar to de-risk a huge quantity of investment whilst leaving it operating within a market, this is near as good as you can expect.

Whilst it was already underway, the CIS comprehensively ends the 25-year NEM experiment in market driven investment. Investment decision making has now fully reverted to governments as it was before de-regulation, albeit now with a commonwealth role.

Operationally however, the NEM should continue, with efficient national dispatch and participant contracting that will continue largely as is. The bureaucrats should be commended for designing the CIS to at least retain part of the NEM furniture.

Thanks for the discussion Ben particulaly around the assessment process. Although a bond of a “few hundred thousand dollars” is not to be sneered at its tiny relative to capital cost of a project and, in my view, nowhere to provide confidence that projects winning contracts will actually be built. Building confidence that projects actually will be built is in a way the entire point of the scheme.

I also wonder whether greater storage depth really is more valuable. Would you rather have 1000 MW of 1 hour storage or 1 MW of 1000 hours storage?

Thanks David. I thought the same re bond. Indeed just the cost of preparing a bid would run to seven figures.

I think the modelling approach proposed sounds quite good for valuing the depth of storage to meet the needs of the NEM, certainly much much better than just dividing by 4 hours in the RCM, which I have heard (but struggle to believe) is also what is used in the much bigger capacity markets of the US.

Your concluding question may be even more rhetorical than you intended, consider this: Battery A can do both roles as the system requires it, but not vice versa.

Excellent insight from WattClarity as always.

One note is that the Vic-SA tender did not apply the four-hour minimum. Whilst present in the consultation draft, it was amended to 2 hours as the tender opened.

Great summary Ben. It seems the Federal Government were left with little choice but “to do something” to drive to 82% by 2030. Given this reality, the CIS is the best of the options on the table and as you say at least preserves much of the wholesale market functionality.