In January 2017 I wrote a paper that contained the reasons why the frequency control on the eastern seaboard was insufficient and poor. A summary article was published here on WattClarity on 23rd March 2017, it included the following statement:

“Reassessment of the approach to frequency control should be undertaken with a view to:

· reintroducing narrow mandated deadbands across the NEM

· removing regulatory disincentives to tight governor action.”

The paper also included an explanation of why the current method relying on “regulation FCAS” was insufficient.

After 32 months of numerous reviews, technical working groups, international expert engagement, another serious event (the double-islanding of 25th Aug 2018) and three rule changes in process the frequency control of the eastern seaboard remains extremely poor. Furthermore, the system is likely to remain poorly controlled for another summer period as rule the rule change process takes months.

The 1 November 2015 event in SA illustrated similar lack of control (the AEMO report is here) while the FCAS markets raked up $65 Mil in local costs.

In September 2018 at an Engineers Australia event on Ancillary Services and frequency control, one member in the audience asked the following question; “You spoke about this a year ago, why hasn’t it been fixed?” The question was answered by the AEMC, who politely explained that their FCAS Framework Review did not consider it an urgent problem. It was clear the engineers expected the problem to be fixed after 12 months, particularly when there are known practical solutions.

The public utilities in each state once employed a small department (about 5-6 engineers) that specialised in system dynamics and control. The system control engineers would test, measure and analyse the control responses of each unit to ensure that they responded to step changes correctly. System control engineering was concerned with co-ordinating the response of all units to ensure that unit controls were working and the collective response of the system was adequate and coherent.

The inefficiency, cost and risk to the power system of the market reviews over the last 32 months far outweigh the cost of the small dedicated teams of system control engineers that once tuned the units.

The international expert report has recommended reintroducing appropriate dead bands on all units, removing control actions that defeat frequency sensitivity, and co-ordinating droop settings across the NEM. This is logical and necessary and does not contradict the recommendations I made 32 months ago.

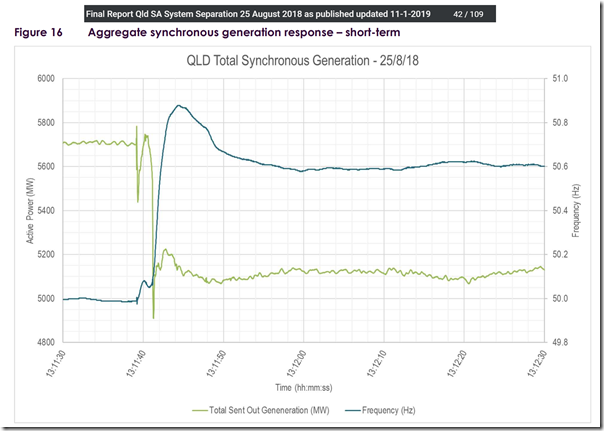

Even within the expert’s report I find two items that appear to be in incorrect when compared with actual local data. Electronically connected generation has been proven to not be sensitive to frequency as is claimed and operates across a wider frequency range than say a gas turbine. Furthermore, the power system is not “well controlled” when the frequency reaches the boundary of the normal operating band. The lack of control is illustrated every time a region separates, the inability to recover the frequency within a separated region is indicative of the lack of control. 25th August in Queensland illustrated this – Figure 16 from the AEMO’s report (copied below) illustrates that the control systems no longer provide an appropriate response for partial load rejection, there is insufficient reduction in active power so the frequency remains high:

(Reproduced from AEMO’s “Final Incident Report Queensland and South Australia system separation on 25 August 2018”)

The current market mechanisms force all error in active power into the frequency, with few understanding the consequences to efficiency or control.

It is clear from the evidence that the market has enabled the detuning of the generators through the cumulative effect of a number of rule changes. This has taken the system from co-ordinated control to competition in control, a highly undesirable outcome on the power system.

Over the years of reform, the rules have altered the power system control philosophy without appreciating the consequences. We see more rule changes and regulatory complexities being piled onto generators without addressing the fundamentals or understanding in full what the problem is that rules are trying to solve. The inability within the market to efficiently correct an identified technical control problem illustrates a fundamental design flaw and a significant loss in power system knowledge.

Are we suffering a system tragedy? Every issue triggers a call for a new policy, new regulation, new “technical requirement” when the fundamentals have not been addressed. Each rule change seems to bring unintended outcomes, often increasing costs and reducing efficient operation. Or do we have blind faith in the “magic of the market place”, thinking that a market knows how to control the power system?

We face another summer with the eastern seaboard at risk again with inadequate control of active power.

—————————–

About our Guest Author

|

|

Kate is a specialist in power system control and technical regulation issues for the NEM and Renewable Energy in Australia.

Kate gained experience at Pacific Hydro (15 years), the Clean Energy Council, the Australian Wind Energy Association and NEMMCO (now AEMO). You can find Kate on LinkedIn here. |

In the coming weeks, Kate would like to share more thoughts on power system control via WattClarity, and elsewhere.

Kate is speaking at today’s ‘Reshaping the Ancillary Services Market of the Future Australian Power Grid’ workshop/forum at RMIT in Melbourne.

I’ve been following this saga with interest.

Of course it only takes a matter of minutes for deadband settings on a governor to be changed.

Primary frequency control is only one of the inherent advantages of synchronous generators.

It’s a shame they are all so under appreciated.

Its seems totally inevitable to me that inertia on the grid is going to keep falling and that as with so many other things we need to start moving forwards.

A workshop from the University of Washington earlier this year contained some excellent presentations and youtube lecture videos that I’ve been working through. I also got a working paper from the workshop convenor that was readable to a determined layman. My own view is that Australia could be moving more in the direction that Europe and the USA are already going. I don’t yet think there is a role for markets in this except maybe for fast frequency control, but I might be wrong. To me its about getting the design principles right for the next 20-30 years at a time when technology in the area is moving quickly. Seminar reference attached and if anyone want’s Brians roadmap document let me know. I’d appreciate input from people who unlike me can speak with authority on an important topic https://lowinertiagrids.ece.uw.edu

I remain perplexed that this problem you have highlighted, not only remains unresolved, but seemingly the AEMC still doesn’t get it. The response to the double islanding event surely underlines the desperate need for this to be rectified. AEMO in their report noted that the last Qld separation event that happening in 2008 involved the loss of power transfer from Qld to NSW of 1091 MW vs 879 MW in the recent event. In that event even though the loss of power was greater the frequency deviation was less in both Qld and NSW and no load was shed to rebalance the system.

Surely AEMC should be able to join the dots.

Kate you make a good case for re-empowering the power engineers — the market design has failed us and its about time that good engineering was given a dominant role again.