Given our focus on serving a broad client base in the energy sector, three particular rule change proposals at the AEMC have caught our attention all around the same time. All three have potential to significantly impact on the business of our clients (existing and potential new ones) in some way. This effect could be positive, or negative (or mixed).

Unfortunately I don’t have a lot of spare time to think through the various implications (and overlaps) of the proposed changes being considered. As such, I only have some glimmers of suspicions – not fully formed ideas that I can articulate as clearly as I would like.

Because of their potential significance, however, I thought it best to post them here in order to some of the thoughts aired below may not stand up to closer scrutiny – however we felt it better to air them here (and have them shot down) than to keep the thoughts to ourselves.

We hope that the staff at the AEMC (who are employed to focus their attention on just such things) are able to take these into consideration.

To all of our readers – please feel free to shoot them down (preferably with a clear explanation of what I’m currently missing).

1) The three rule change requests

Request #1) Establishment of a “Negawatt Buy-back Mechanism”

That’s not the official title of this rule change request, nor is it the proposed name for the new method. However I’ve taken to calling it that in order that I don’t add to the confusion the proposed new method is likely to generate (given that there are already a number of other methods for demand response that operate in the NEM).

This is the oldest of the three in this bunch – it’s been bouncing around the traps for a number of years (having arisen as one piece of work flowing out of the “Power of Choice” review, stage 3 of which began way back in 2011).

Submissions are due on this part by 10th December 2015 (two weeks away).

I’ve previously commented, with respect to this method:

(a) on how prices might be set, and

(b) implications of the FERC ruling in the US.

Request #2) Bidding in Good Faith

On 13th November 2013 the Minister for Minerals Resources and Energy in South Australia submitted this rule change request to the AEMC, as a result of which this rule change process was initiated.

Submissions were due by 29th October 2015 (though a late submission might still be accepted).

Coincident with this process has been a number of claims of “price gouging” and so on in the media.

In more general terms, energy users have expressed concern at the high level of forward prices seen for South Australia and Queensland into 2016. I posted comments here to follow a longer-term theme of the concerns of energy users.

Request #3) Demand side obligations to bid into central dispatch

This rule change proposal is the newest of the three – a consultation paper was published on 5th November to follow the proposal from Snowy Hydro on 10th June 2015.

Submissions are due 3rd December (Thursday next week).

My sense is that all three rule change requests are related – complimentary in some ways, but also conflicting.

I’ve also been grappling with the possibility that these proposed changes are piecemeal solutions (bandaids) on a NEM framework:

(a) that has an unresolved deficiency that’s delivering perverse outcomes;

(b) that is being asked to cope with structural shortcomings, and

(c) that looks set to be asked to make a massive transition for which it was not designed.

2) About the Demand Side, and about Demand Response

We’re a keen supporter of Demand Response, as I previously noted here. Indeed, through 2015 we have been, as time has permitted, building up this reference site with the aim that it might grow to become a reference to all the different ways in which demand response functions in the Australian National Electricity Market (NEM):

www.DemandResponse.com.au

(we’re very keen on your input, if you are involved in some form of demand response in any way, to ensure the site reflects the full range of possibilities).

For readers that know us I hope I don’t need to reiterate – we strive to remain “technology agnostic” and hence view demand response as one more option of providing peaking capacity into the energy market (so I would hope we would not be labelled a “demand response zealot” for instance).

Given our position in terms of how we support demand response in the NEM, these rule changes fall into:

(a) An area of particular interest to us; and

(b) Where our insights, in terms of how demand response actually functions (at least to the extent we are aware), might prove useful in this deliberation.

Looking at the Snowy-proposed rule change (which is focused on the types of energy users we serve), I’m still trying to get my head around what the real problem is that this proposed change is trying to solve.

2a) What seems to be Snowy’s position?

In essence, Snowy seems to be saying that, because they don’t know (because it’s confidential, currently) the way in which some particular energy users (but not all) procure their energy, they are unable to operate in the market as efficiently as they would like.

2b) Our experience of how Demand Response functions

We help energy users operate with demand response in this particular way.

For the avoidance of confusion, please note that there are a number of other categories of demand response which:

(i) We currently provide less service in; and

(ii) Which don’t seem to be the target for this particular rule change.

In these other categories demand might change but, because it would not be in relation to spot prices, it would not seem that it would be covered under what Snowy intend?

The energy users who we serve (in helping them physically manage the risk of high spot prices) are a diverse bunch.

However there does seem to be two underlying commonalities that should be borne in mind with respect to these rule changes:

(1) These energy users are in the business of widget-production, not electricity trading (despite the fact that electricity purchase cost represent a significant share of OPEX); and

(2) These energy users are also operating in the manufacturing sector, oftentimes trade-exposed, feeling the stress of foreign competition and real stakeholders in the long-term decline of manufacturing as a share of GDP in Australia.

With the energy users we serve, we provide a software service but will only occasionally be called in to help in developing operational processes for the site, in relation to the spot prices. Hence our view of how they operate might be incorrect in some ways (and certainly won’t be an accurate reflection in every case).

It’s our understanding that these energy users might give some cursory attention to what’s shown in predispatch, but generally won’t pay it much heed as they see it as a feedback loop through which generators adjust their bidding strategies to maximise returns (as they are allowed – though constraints on this might change with the 2nd rule change proposal, advocated for by some of these energy users (amongst others)).

Instead it is only within a trading period itself that a curtailment decision is made.

2c) What’s the data say?

Given the way energy users actually operate (at least in my experience), I undertook to crunch some numbers to see what difference their curtailment might be making to actual levels of demand.

Of course, to do this with 100% precision is impossible (because individual arrangements are confidential) but I believed it would be possible to observe some overall results from region-level data.

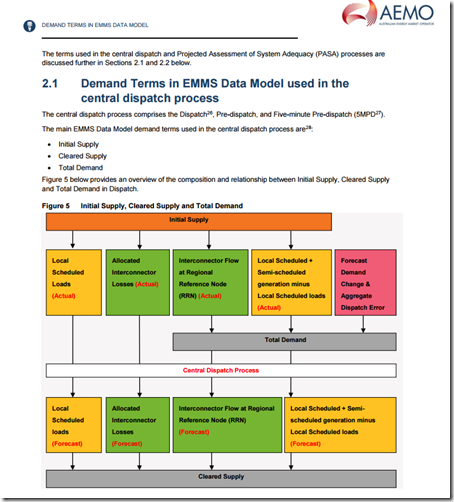

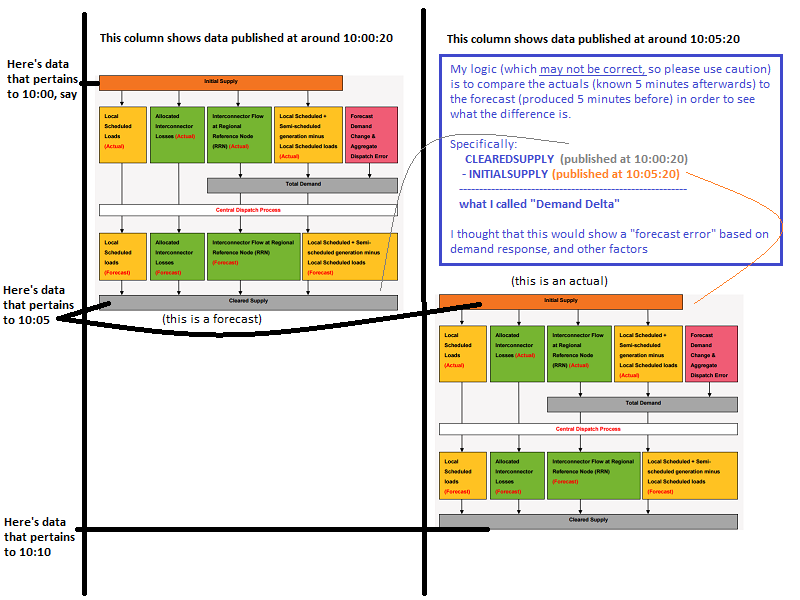

The AEMO has recently published a document “Demand Terms in EMMS Data Model” that helpfully includes this diagram to explain the three main terms used for “Scheduled Demand”:

We believe it follows, then, that comparing CLEAREDSUPPLY (i.e. the forecast/target demand number generated at the start of a dispatch interval) with INITIALSUPPLY (i.e. the actual demand number from the start of the next dispatch interval) will show how much demand has varied from what the AEMO expected over that 5-minute period.

Unless I am misunderstanding something, what Snowy seems to be implying is that this “demand delta” will be higher when spot prices are above the trigger level – and that this higher delta is causing issues for them.

The following is what I have been able to observe at this stage in crunching the numbers. As time permits I will seek to continue this analysis (please suggest how below) but, because of time constraints, it won’t be tomorrow when i get that done, unfortunately…

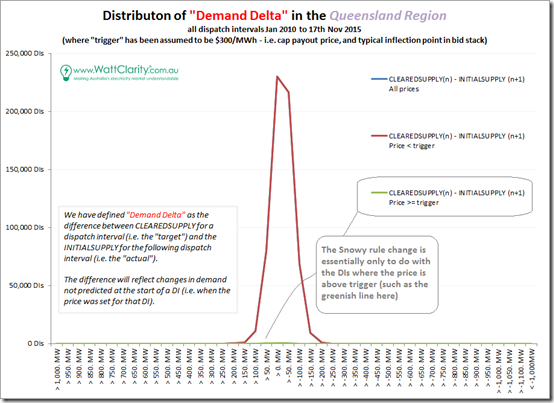

(i) Observed “Demand Delta” in Queensland over almost 6 years

Starting with the Queensland region, I retrieved dispatch data from 1st January 2010 to 17th November 2015 (when I performed the analysis). With the data, I compared the “Demand Delta” across 2 scenarios:

(a) Price below a trigger price (i.e. assumed no demand response)

(b) Price above a trigger price (i.e. assumed demand response to the extent that it exists, and is observable).

Important, in this paradigm, are two assumptions:

(a) That the INITIALSUPPLY (forecast at the start of the DI) did not assume the demand response (which is what Snowy seem to imply) and that the CLEAREDSUPPLY (measured at the end of the DI) does reflect this.

(b) In our experience, different clients curtail at different prices at different times (and this depends on a range of parameters that we are not privy to). To provide a starting point, we assumed a trigger price of $300/MWh (being the cap payout price, and also an inflection point in a typical bid stack).

The following chart resulted (click on any chart for full-screen view):

As can be seen on the chart, the DIs in question (the light green line squished at the bottom) reflect the small number of DIs when the spot price was above $300/MWh over that five-year period.

Following comment with Chris Deague (below) I have added a PS at the bottom in which I try to explain, more clearly, the method used. Note that I am still grappling with whether this method was appropriate, or not.

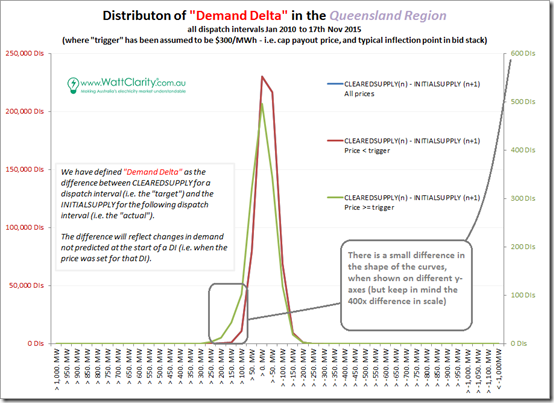

Swapping that distribution to another axis, we see this 2nd chart:

In this chart we do see that the green distribution is skewed a little to the left (i.e. fitting the logic that demand response to high prices means demand drops more than “normal”).

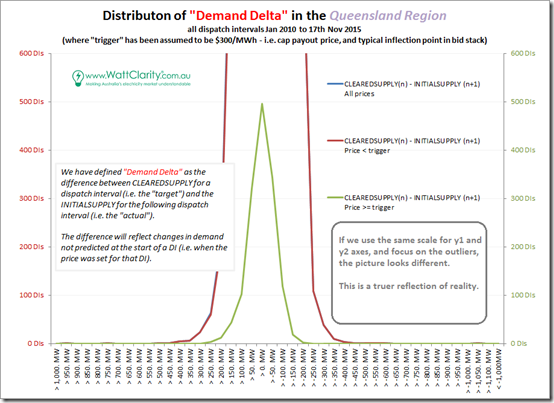

But how significant is this difference? Here’s the same chart with the y1 axis set at the same scale:

It’s pretty clear from this chart that there are have been many more instances over the 5-year period where the demand has been lower than AEMO forecast at the start of the DI (i.e. “Demand Delta” negative) .

Hence I wonder if Snowy’s perceived issue is real, or moreso a representation of confirmation bias?

Their hypothesis would have made more sense if the green distribution was skewed way over to the left. Instead, we see it (in the third chart) sitting neatly in the middle of the “all other DIs” distribution.

In this way, if “demand delta” is a challenge (which I can understand it might be) it would seem logical to find a way of making dispatch targets more accurate across the board, rather than focusing on one particular scenario that operates a very small percentage of the time.

Or am I missing something?

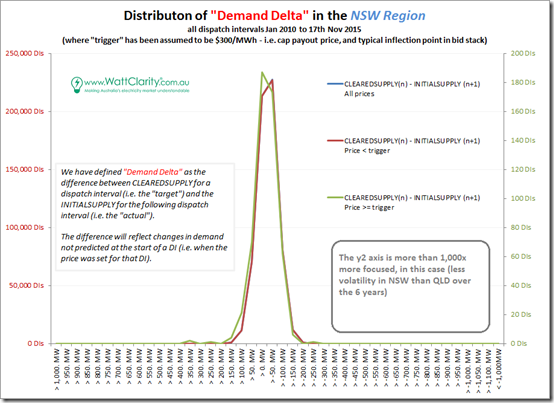

(ii) Observed “Demand Delta” in NSW over almost 6 years

Here’s the same version of the 2nd chart above for NSW:

It’s been less volatile in NSW than in QLD over the course of the past 5 years, so perhaps that is a reason there’s almost no observable difference between the two distributions (on two different scales).

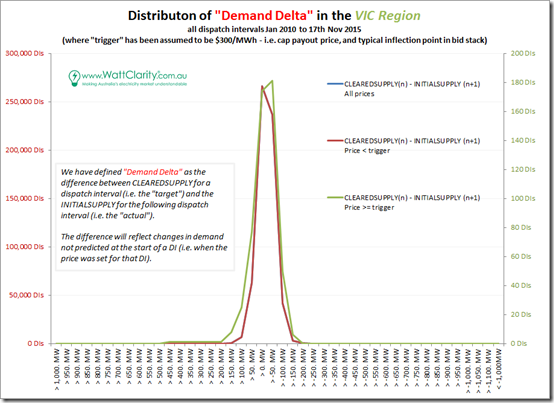

(iii) Observed “Demand Delta” in Victoria over almost 6 years

Again for Victoria we see the same sort of thing:

The green distribution (on a much smaller scale) looks to be slightly broader than the “all other DIs” distribution.

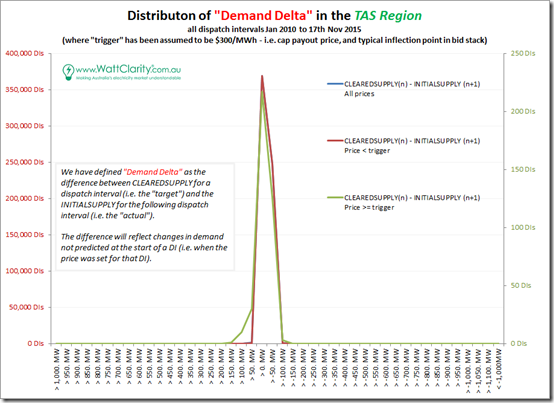

(iv) Observed “Demand Delta” in Tasmania over almost 6 years

Here’s the same for Tasmania:

Now here we can see a kink in the green (price > $300/MWh) distribution out to the left – but keep in mind, again, the grossly different scales shown.

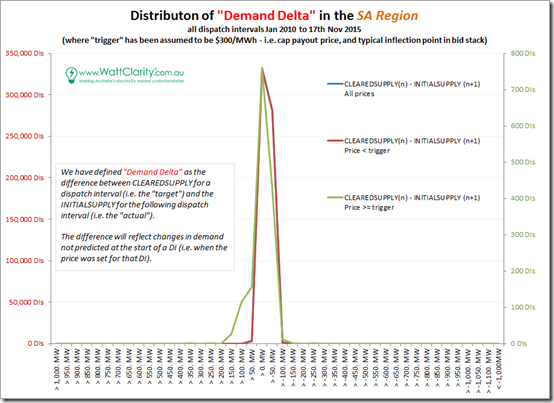

(v) Observed “Demand Delta” in South Australia over almost 6 years

Finally here is South Australia – which has been (along with Queensland) one of the two most volatile regions over the period:

In this case a bit more of an extended kink out to the left – which would seem to indicate a demand response to high prices.

But keep in mind the different scales to conclude on its significance.

What the above seems to show is that there is a normally occurring level of “demand delta” – and that the level of “demand delta” believed to be from price-responsive demand appears to be well within this normal level.

Reminds me, a bit, of the story of the guy looking for what he’s lost under a streetlight (because it’s easier to see there) despite the fact that he lost them elsewhere…

Am I missing something?

Why single out:

(a) these particular DIs (i.e. responding to price, but nothing else)?

(b) only big manufacturing loads?

Snowy says “it is self-evident that any load which is responsive to price has an impact on the price discovery process”. Whilst this might be true, is this not just a subset of saying that any demand change (whether triggered by price or for other reasons) has an impact on price?

Perhaps it can be argued that these particular dispatch intervals are particularly important, given the outsized effect that price spikes have on average prices in the physical market.

This is the same sort of argument that seems to have been made by proponents advocating for rule change #2 in the list above (in that case I wonder whether a similar type of phenomenon is at work – whereby once we develop a paradigm of “greedy generators” then anything other than bidding short-run marginal cost becomes “price gouging”).

Or am I missing something there, as well?

2d) What other analysis might we perform

My reading of the Snowy proposal is that it really revolves around 4 different time intervals –

Time period 1 = within the dispatch interval (which I have tried to analyse above)

Time period 2 = within the current trading period. This is relevant because of some of the bizarre outcomes that we’re seeing in the NEM because of the 5/30 issue (discussed more below). Depending on feedback below, I may try to look into this more in a future post.

Time period 3 = further out into P30 predispatch. However on reflection I’m not sure this really makes sense (i.e. if demand response is observed within the same dispatch interval to be well within the normal bounds of “demand delta”, how much moreso would this be a day ahead, say, given all the vagaries of weather and what all the other 99.99% of the energy users will be doing?)

Time period 4 = out into financial contract horizons (months and quarters). I’ve not had time to think through this in any detail, but would appreciate your comments below (please!)

3) Encouraging more unintended, perverse outcomes?

In an ideal world it seems clear to me that all wholesale Market Customers would be required to bid to consume on a similar sort of basis to how generators bid to produce currently in the NEM. In this way, the organisation “most” responsible for the consumption would be required to nominate in advance for it – instead of the AEMO being saddled with that responsibility and then being bashed for getting it wrong.

However that’s not been practical, at all, in the past. As technology improves, the barriers to this being possible should reduce (though changes like this seem to be heading in the other direction) – however our sense is that this is still some years away from being possible.

3a) The 5/30 issue

At a forum conducted by the AEMC on the 2nd rule change above (bidding in good faith) a question was raised about the 5/30 issue – following from which one of our guest authors posted on WattClarity about the 5/30 issue.

I do wonder about the extent to which two of these rule changes are seeking to address the perverse outcomes facilitated by the difference between dispatch and settlement timeframes.

Part of me wonders why no-one has submitted a rule change to test whether NEMMCO’s conclusions from more than 10 years ago (that it did not stack up) are still relevant, given developments in big data, etc…

3b) What might be required (of more flexible demand) in future years?

The NEM is faced with great uncertainty in terms of how the supply and demand mixes might be constituted in the future – because of technological change, because of the unresolved carbon/energy nexus, and for other reasons.

There are certainly many who advocate a future consisting of a higher percentage of intermittent generation supply, coupled with copious amounts of storage and other forms of demand response. Whilst this is far from certain, and other futures might evolve, it perhaps might be instructive to wonder how Snowy’s proposed rule change might work in this environment?

Snowy says “the situation is likely to get worse and result in further degradation of efficient price discover with better technology that enables more demand response, more distributed generation and more non-scheduled generation which will make scheduling of generation more difficult and uncertain”.

I agree with these concerns – which is one of the reasons why I have invested time to perform analysis such as this for All Energy.

However I do wonder whether a rule change that targets only loads more than 30MW is going to provide an ounce more transparency for any of these growing sources of demand flexibility.

In one of the submissions I read to one of the rule change (apologies, they all blur together after a while – I think it was from RWE but would like to confirm later) I recall someone making a comment along the lines of how the way operations were evolving, it was like the NEM was valuing flexibility over technical efficiency. To me this does seem to be the case, and for what seems to be good reason, if this is already emerging as the future…

3c) Reducing spot-exposed demand, but increasing negawatts?

The thought has occurred to me that, if all 3 rule changes were to proceed, it might prove easier (and less intrusive, in real time) for large energy users to opt out of the method they currently use and, instead, provide demand response through what I have called the “Negawatt Buyback Mechanism”.

* if (and when?) the rule change to create the “Negawatt Buyback Mechanism” does go through, then we will be very keen to serve those energy users who choose to operate in that way, and maximise the benefits they derive from their participation.

Under this mechanism, an energy user’s gross consumption (deemed profile) would not be published in the MMS and would only be available to directly related commercial parties sometime after the event. Instead a negative consumption would be all that would show in the MMS on a day-after basis – whilst we add into the mix an incentive on the part of these energy users to inflate their consumption profile leading into events when they are likely to be called on to dispatch negawatts, as some energy users have told us that they sometimes do when covered under this arrangement).

Rule change #1 and #3 do seem opposed. If both went through, would this outcome actually add to transparency – or reduce it?

Especially if you have made it all the way to the bottom, I am very, very interested in your thoughts (but, coincidentally, am taking a few weeks leave so might be slower to respond than otherwise)

Thanks, in advance, for your comments (below, via email, or in person)….

PS (added Fri 27th Nov) about the method used for analysis

Following Chris’ comment (and some questions asked offline) I have added this image here to help explain the method I used:

Note that I’m trying to understand if the method I used is credible, or not -> it does seem to show a high number of DIs where AEMO’s dispatch targets are “off” by a significant amount.

If it’s not credible, I would really like to understand why – hence please do add comments below, or email me direct, to continue this process though note I may be slow to respond as I am hours away froms starting a holiday

Paul,

I think that you have incorrectly characterised the issue that Snowy are flagging in their Rule change.

You have suggested that the the delta between CLEAREDSUPPLY and INITIALSUPPLY represents how much demand has varied from what AEMO expected over that 5-minute period. This is not the case – in fact the difference between these two variables is exactly equal to the amount of demand change that AEMO have forecast for the 5-minute period.

The problem that Snowy have highlighted is that after AEMO issue the 5-minute price and dispatch targets, non-scheduled loads (and generators) can suddenly change their consumption/supply, which is seen by the NEM as an unexpected change in demand. The scheduled generators however are required to continue to ramp to their 5-minute dispatch target.

As an example, suppose that AEMO forecast that the demand in a region is expected to increase by 20MW in the next 5-minutes, and calculate 5-minute price of $300. AEMO issue a dispatch instruction to the marginal generator in that region to increase its output over the 5-minutes period by 20MW to meet the expected demand increase. The marginal generator then commences increasing its output to achieve a 20MW increase by the end of the 5-minute period.

However, other non-scheduled entities note the high 5-minute price ($300), and choose to reduce their consumption in aggregate by 50MW. This demand reduction was not anticipated by AEMO, and despite the fact that the demand is now 50MW below what was expected, the marginal generator needs to continue increasing according to its dispatch target (or risk being declared as non-conforming).

AEMO need to balance the power system supply and demand, and they do this by reducing the output of the generators assigned to frequency control.

At the end of the 5-minute period, AEMO then “capture” the fact that the demand reduction of 50MW has occurred, and then ask the marginal generator to ramp back down again.

The intend of the Snowy rule change is enable AEMO to anticipate the 50MW demand change, and prevent the unnecessary and inefficient ramping up and down of marginal generators and frequency control services, and the resultant inaccurate pricing forecasts.

Thanks for the input, Chris

I’ve added a PS to the post to explain my method:

https://wattclarity.com.au/2015/11/puzzling-through-three-rule-change-requests/#method

I’m genuinely interested to understand what I have done wrong?!

Paul

PS Unfortunately I’m heading on leave today for 3 weeks so will be slower to respond than would normally be the case…

Paul interesting analysis.

I would only add that everyone is paid on the half-hourly price and so may respond after a high price event. How do the graphs look if the trigger price uses the settled price rather than the dispatch price?

Ben

Thanks Ben

Been away on leave so no time to respond. The 5/30 issue does complicate this consideration in a number of different ways:

1) You note that generation (or negawatts) might respond after a 5-minute price, so long as it’s in the 1/2 hour. This is one permutation.

2) Another is that those participating in this way might try to pre-empt spikes by dispatching based on predispatch prices, gut feeling, or some other method.

I don’t have time to delve more presently, but will see if I can return to this in future…

Paul