Power outages have long been a fact of life in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Particularly over the humid summer months where the air-conditioners are permanently switched on. While staying in Buenos Aires for five months in 2017, street navigation by back-lit phone, and (non-romantic) candle-lit dinners, were common events. What has caused this? Ultimately, the poles and wires and substations that make up the city distribution networks (distribution infrastructure) can no longer sustain demand. This has badly impacted the reliability of the network, but (as we shall see) has also impacted on retail prices.

By way of contrast, Australia is a case study in how over-investment in distribution infrastructure can inflate retail prices. I call this the Network Investment Paradox: Invest too little, price rise; invest too much, same thing happens. I examine the phenomenon and ask; are the regulatory policies implemented in Australia enough to maintain the right balance of network investment going forward?

1) Understanding Under-Investment

The causes of network under-investment in Buenos Aires (and Argentina more generally) are complex and interwoven with broader economic, social and regulatory trends. The distribution networks were privatised in the early 1990s with two private companies Edesur and Edenor (the distributors) running the distribution networks for the south and north of the city respectively. Throughout the 90s there was relative reliability and stability to the distribution infrastructure due to regular maintenance and upgrade.

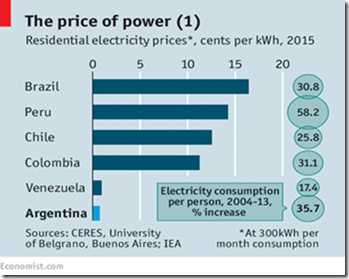

This changed, however, with the Argentine economic crisis of 2001/2002. The federal Government froze electricity prices, (including the regulated network component) to relieve pressure on consumers. While the distributors limped along via subsidies, inflation and repeated political interference in network cost recovery, stymied distributor access to capital and disincentivised investment in the distribution infrastructure. With retail prices frozen, and inflation rampant, consumers had no incentive to reduce their demand on the system, despite paying an ever-decreasing proportion of the cost of that electricity. The graph below from The Economist shows the effect very low electricity prices had on electricity consumption in 2015.

This demand in combination with a swelling population has resulted in a network that can no longer guarantee reliable supply.

The election of the Macri Government in 2015, saw a plan to improve distribution infrastructure and for utility bills to better reflect the cost of producing the utility. Combined with pressure from the International Monetary Fund to manage the deficit, in the last two years Buenos Aires has experienced massive jumps in retail prices. The most recently slated increase is for an average of 55 per cent per consumer (noted here). Increased retail prices have facilitated a range of network investment to improve the distribution infrastructure.

See, for example, https://www.smart-energy.com/industry-sectors/smart-grid/edesur-argentina-enel/, for improvements occurring in the broader province as well as in the city of Buenos Aires.

In short, the costs of chronic under-investment will eventually be passed on to the consumer, and likely at a higher cost than would result from regular maintenance and upgrade.

2) Understanding Over-investment

The ‘gold-plating’ of Australian transmission and distribution networks has been the main driver of rising retail prices over the last decade or so. The ACCC Retail Pricing Inquiry and the Australian Energy Regulator (AER) identified inefficient regulation of network pricing as the cause of this over-investment (see page 158).

Previous regulatory settings meant that the AER had to accept expenditure proposals if it was satisfied that they ‘reasonably reflected’ efficient, prudent and realistic expenditure. This enabled distributors to submit the highest possible demand forecasts and, left the burden for the AER to show that the distributors did not meet the standard. Those forecasts, in turn, enabled distributors to invest excessively in the reliability of distribution infrastructure.

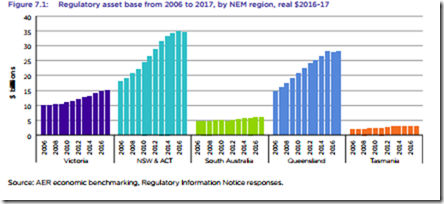

The graph below demonstrates this trend by showing the increased in the ‘Regulated Asset Base’ for distributors over time (see page 159).

Focusing on the 2014-2016 period this graph shows the increases starting to level off. This has been attributed to a range of regulatory measures including:

- giving the AER greater ability to assess network revenues and proposed costs;

- a focus on benchmarking and changes in assessing debt and rate of return; and,

- increased stakeholder participation in price-setting.

3) Lessons for Australia

It is essential wherever distribution infrastructure is privatised that the right incentives are in place to support reasonable investment in the upgrade and maintenance of that network. If the business’s ability to make a reasonable return is stymied, that investment won’t happen. However, excessive investment will unfairly pass extra costs on to consumers.

While network investment in Australia is arguably approaching a reasonable balance between over and under-investment, are there any emerging trends that should make us worry?

There are two trends that are worth pondering:

3a) Embedded Networks

Private electricity networks, often called ‘embedded networks’ and located in apartment buildings, shopping malls, retirement villages and caravan parks, are a growing form of electricity distribution in Australia. It is estimated that there are between 3,000 and 4,000 embedded networks in National Electricity Market jurisdictions, serving between 213,000 and 227,000 customers (see page 15).

While the Embedded Network Operators (ENOs) are entitled to pass on the costs of the wider distribution network to their small customers, they are not permitted to charge for the costs of maintaining and upgrading that private network.

See Electricity Network Service Provider – Registration Exemption Guideline, Version 6, March 2018, p64. While there are reforms in development intended to require ENOs to register as a class of distributor, there are no proposals currently that they will need to meet the reliability standards of distributors or to allow ENOs to charge for internal network costs.

This means that there may be insufficient incentive for ENOs to invest and ensure that their networks meet reasonable reliability and security standards. Over time, this could lead to significant under-investment in the resources used to supply customers.

3b) Embedded/Distributed Energy Resources (DER)

The rise of solar power in Australia has meant a significant increase in embedded or distributed generation. This is small-scale, de-centralised generation connected to the grid at a distribution (rather than transmission) level. Common instances include rooftop solar PV, battery storage, electric vehicles (EV) and EV chargers, as well as demand response initiatives.

There are concerns that this might have an impact on the broader network (see page 1). Concerns include:

- overstated or understated network demand forecasts through a failure to account for behind-the-meter generation. This could affect distributor forecasts as well as those made by the market operator (AEMO);

- safety risks to workers, installers and the general public through emergency services and line workers or electricians not having adequate information on sites with distributed energy resources.

A planned register of distributed energy resources (Guidance is expected to be released in mid-2019) may improve visibility of these assets.

| Editor’s Note At Global-Roam, we collaborated with the Energy Storage Council (now the Smart Energy Council) to invest considerable resource into the development of an Energy Storage Register that would operate on a beneficiary-pays basis. This process began prior to the COAG Consultation, and continued in parallel with this – and is discussed here. Given the route chosen by COAG as the result of this consultation, we suspended further investment in our proposed solution. |

In the case of both embedded networks and DER, regulators need to take special care to ensure that there is transparency across the broader network and incentives in place to ensure sensible investment.

About our Guest Author

|

Dr Drew Donnelly is a Regulatory Specialist with Compliance Quarter.

Dr Drew Donnelly holds a PhD in Legal and Moral Philosophy from the University of Sydney. He has extensive government experience including as policy analyst. In Compliance Quarter, Dr Drew helps new entrant retailers with their regulatory compliance. Compliance Quarter provides world-class systems and expertise to energy retailers and other market participants You can find Drew on LinkedIn here. |

I think the cost of an underinvested network should include the cost of blackouts due to capacity shortage. This is logical because an overinvested network shouldn’t have a capacity shortage.

How you’d measure or estimate the cost of a blackout I’m not sure.

I’d like to hear perspectives on the cost of network not related to demand, but attributed directly to reducing congestion from intermittent generation or facilitating new intermittent source connections. The demand is not increasing (rooftop PV) but the networks are…

Absolutely. The cost of blackouts is not just limited to the cost of fixing the infrastructure and getting it back up to code, but also the serious flow-on effects of power outages to the broader economy which will not occur with over-invested networks.

On the second point, the impact of increased intermittent generation is a major concern for regulators. As well as the impact on dispatch forecasting which I mentioned above, the AEMO is concerned about:

-the effect of DER generation in excess of regional demand during periods of minimum demand. There is no current mechanism to constrain down generation from DER;

-the progressive displacement of synchronous plant by inverter-connected DER plant removing inertia from the system. This challenge for system security and reliability was a major concern for the Energy Security Board in developing the National Energy Guarantee as well;

-the challenge of maintaining voltage within technical limits without visibility of DER.

Dealing with DER is going to be costly. Whether that cost is best passed on to retailers through a National Energy Guarantee is another question

For more discussion see the AEMO report (https://www.aemo.com.au/-/media/Files/Electricity/NEM/Security_and_Reliability/Reports/2016/AEMO-FPSS-program—-Visibility-of-DER.pdf) and the AEMC report (https://www.aemc.gov.au/sites/default/files/2018-09/ERC0227%20-%20DER%20register%20-%20Final%20Determination%20%28final%29.pdf).

Thanks Drew (for the original article and the response)

The AEMO report has some particularly interesting language around conservative safety margins and larger reactive reserve thresholds – all reducing efficiency of the system.

It seems the current market and regulatory environment are not set up to pursue the most efficient system of generation, transmission and distribution.

I find the “gold plated” argument frankly annoying. For starters, those who perpetuate the myth clearly have no knowledge of the external boom, bust, boom cycle that caused these gyrations in network investment.

Unlike Drew, I was there. I doubt Drew has ever stood beside a 50 year old creaking 110kV switchyard running above full load, hoping like heck the nearby circuit breaker wasn’t about to explode into a fireball, and wondering if he would be alive to see his wife and kids at the end of the shift. I did. More often than I cared to. (So, please excuse the passion.)

It is not a problem these days, but it sure was back in the summer of 2004. Every night, the local TV news would broadcast pictures of power transformers in Brisbane suburbs being sprayed with fire hoses in a desperate attempt to keep cool. How badly overloaded? Well Albany Creek had 30MVA load on two by 12.5MVA (25MVA firm), and these transformers were originally 10MVA uprate to 12.5MV.A with fans (no oil pumps).

Or how about 260MVA daily summer peaks at Victoria Park substation on two by 120MVA (240MVA firm). Note this is well above N-1. Even better, one of these 120MVA transformers had an electrical age of 50 years and wet windings. But under the severe capital rationing that Energex was under at the time, there was no funding to replace it. At the time Victoria Park supplied critical load like the Royal Brisbane Hospital (arguably Queensland premier hospital), St Andrews Hospital, and Brisbane Central Hospital, and a quarter of the Brisbane CBD. I could go on, but you get the idea of what the network was like in 2004.

Which is a nice segue into the AEMO report that Drew mentions. Why does the AEMO report select 2006 as the start year? My view is because it slants the story in the direction its author’s want it to. Why not start the comparison in network expenditure from, say, 1996? Because it tells a completely different story, and one that runs counter to their argument, and deflates the “gold plated” investment story.

But it goes back even further than that. The electricity industry in Queensland had a significant investment boom in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s for an anticipated mineral boom that never really eventuated. (It did, 25 years later.) This lead to severe capital rationing in the mid-1980’s and coupled with a strong push on cost savings via use of contractors, lead to the SEQEB dispute of 1985. After the government won the SEQEB dispute, there was even more rationing of capital in the late 1980’s across the entire Queensland electricity industry. Buoyed by their success, the economists kept up their severe capital and operational expenditure rationing during the 1990’s. And why shouldn’t they? After all the engineers were just gold plating the network.

In Energex’s instance, along came Greg Maddock in 2000. Greg was an economist. The short story is that he too believed in the “engineers are gold plating argument” and decided to cut network investment even further.

But something else was happening at the same time. Yes, electricity tariffs were low (around 14c/kwh), but the Queensland economy was moving along at a great clip. Price of electrical appliances, in particular air conditioners, was decreasing. Net migration into Queensland was running at 1000 people per week. Mining investment was starting to increase as well. But investment in the electricity grid did not follow.

Something had to break. And it sure did in the summer of 2004. Yes, the EDSE report provided some details into how bad things were. But it is what happened behind the scenes that explains what happened next. Economists and regulators all over Australia saw clearly for the first time how their “regulation” had resulted in significant under investment and this had taken the electricity network to the edge of the abyss. They peered over the edge into the black(out) below and knew what they had been doing was clearly wrong, and if it continued they were about to be publicly flogged.

So, the economists threw the problem back into the lap of the engineers and said; fix it, money is no object. So, not only did the expenditure in 2005 to 2015 have to match the phenomenal grow of the day, it also had to fix up the under investment of the last twenty years as well. Hence, the investment megacycle.

This is the true reason why the investment in the grid – yes “investment” not excessive gold plating expenditure – in the (very suspect) AEMO chart looks the way it does.

Now, if you think this is a fairy tale told by a grumpy old electrician, I point you to two excellent papers.

Simshauser, P. and Catt, A. (2012), “Dividend policy, energy utilities and the investment megacycle”, The Electricity Journal, 25(3):4, 63-87.

And the classic “death spiral paper”

Simshauser, Paul & Nelson, Tim. (2012). The Energy Market Death Spiral – Rethinking Customer Hardship.

The death spiral paper is more accessible outside of paywalls. Check out figure 3 in this paper (which has CAPEX investment from 1955 to 2011). Note the investment peak in the early 1980’s. Note the investment blackout in the 1990’s. And note the investment mega cycle (Simshuaser & Catt’s term) from 2005.

But, there is more.

This investment mega cycle in the Queensland electricity grid (hopefully the gold plating argument is now looking exceptionally weak) occurred in the midst of a once in a lifetime mineral boom. Not only was coal seam gas (and LNG trains) coming on stream, there was rampant mining activity in Queensland. Mining companies too were chasing electricians, electrical contractors, and things that contain copper and spin. The prior under investment had also result in under investment in apprenticeships. Guess what happened next? Wages boom for sparkies.

Take the price of copper (the stuff transformers and power lines are made of). In late 2003 the price of copper was around $1500 per metric tonne. By 2007 it was near $8000 per metric tonne, peaking just short of $10,000 per metric tonne in 2012. The raw material – copper – that is integral to the electricity network has risen by over 600% !!!!!!

The icing on the cake was the regulator’s decision on how to calculate WACC. Despite being warned by electricity utilities in their regulatory submissions, the AER decided to change the WACC calculations. Then along came the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, and the cost of capital went through the roof. This too added to customer’s electricity bill.

So I see a completely different story. Where some see “engineers gold plating” the network, I see inept and clueless economists causing bust and boom cycles in investment. Where some see over investment in the decade from 2005, I see chronic under investment and missed opportunities (when costs were at record lows during the late 1990’s) to make sensible investment decisions for the future.

As for the future, well, that is another story.

Dr Anthony Spierings is a registered electrician. He holds an Associated Diploma in Electrical Engineering. A degree in Economics, Banking and Finance. Master of Project Management. PhD in Information Systems. He previously worked at Energex for 35 years; including extensive stints in substations, project management, program management, and network operations.

Anthony, I was ‘there’ too. And I can tell you, at that time in history, gold plating is an apt description. The other difference in our experience was my employer took a little more care with WH&S. Why an earth did they put you in such situations?

Anthony, I appreciate your perspective on the QLD system. Here is one source for the “gold plating” label.

https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/backgroundbriefing/2014-06-29/5549868

Thanks very much for this, Anthony. There is a lot there that I didn’t know about pre-2006 investment and thanks for the links to other articles. It is a good reminder for me (and maybe all of us) that regulators and policy-makers are often partial to a certain narrative and we always need to look at their reports and reviews with a critical eye.

More on “gold plating”…

https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/electricity-industry-threatens-farmer-who-dared-to-fight-20121109-293wf.html

https://www.smh.com.au/business/power-sector-primed-for-overload-20120530-1zitp.html