In his guest authored article on WattClarity last week, Stephen Wilson made the important point that different people can be thinking of different timescales when they talk about ‘the Market’ in discussing the question ‘Does the NEM need to be redesigned?’.

Whilst all timescales are necessary components in the entirety of a functioning market, it’s easy to see that there can be misunderstandings if participants in the conversation are not even aware:

1) That there are different timescales; and that

2) Others in the conversation might have a different frame of reference.

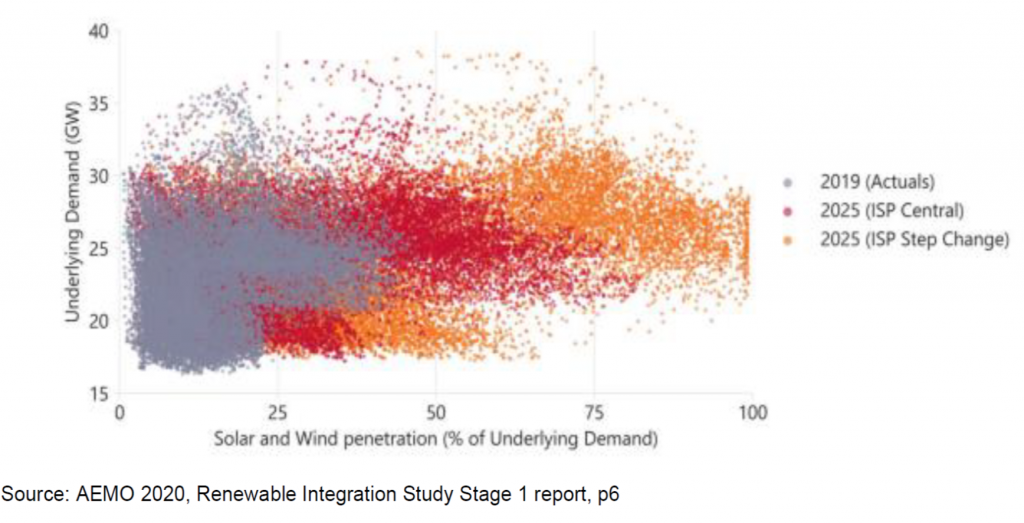

I’ve had a similar experience recently when speaking with different people, and reading conversations online, referencing the following diagram from AEMO’s inaugural ‘Renewable Integration Study’, released on 30th April 2020:

… and so I’ve recognised that it’s useful to begin conversations with the question:

What do you see when you view this chart?

In what I have seen, there seems to be differing interpretations:

What it is

AEMO presented the chart to illustrate percentage instantaneous penetration of Wind and Solar NEM-wide for three years:

(a) Actual results of 2019

(b) Modelled outcomes for 2025 assuming the future proceeds like the ‘ISP Central’ scenario; and

(c) Modelled outcomes for 2025 assuming the future proceeds in the alternate ‘ISP Step Change’ scenario.

What it isn’t

Unfortunately, others have confused instantaneous values with ‘over time’ aggregates or averages … but that’s a different story.

I wanted, in this article to ask you, the reader, whether you see in this:

- The (projected) speed of the energy transition?

- The related convergence of generator wholesale market earnings towards a short run marginal cost of roughly zero for all practical purposes, as the share of wind and solar in the generation mix increases?

- Or both?

This chart, which the ESB referenced in a presentation earlier this month, gave me a frame for an issue that the Integration System Plan highlighted – intermittent renewable generators may not be making money in the future.

Will intermittent generators achieve sufficient return?

By making money, I mean generator total earnings are sufficient to provide a respectable, risk-based return on lifetime investment.

Are any generators making money in this world? Wholesale market (spot) and contract prices are related, with the relationship flowing from spot to contract prices. As spot prices fall, you would expect contract prices to fall too. As contract prices fall, the protective shield offered by conventional generators to renewable generation in setting the spot price above renewable generators’ costs falls away, as can already be seen in spot prices in the South Australian and Queensland markets in high solar production periods (as explored in this review of prices for Q2 2020, for instance).

Of course, part of what’s going on is small scale solar PV is eating generators’ lunch (a severe case on 13th October in Queensland), but let’s not get into that right now.

In a further and related problem, while there’s still money to be made in specific well-defined and necessarily well-paid circumstances in the current market by specialist generators and some conventional generators, the prices of caps and other options have fallen. The changing nature of the opportunity for caps and options and the unknown incidence of those events in future is deterring investment in specialist generation.

By the way, has anyone yet seen the wave of generation investment that was anticipated in response to the shift to five-minute settlement? That change starts in under a year now.

Do we get to this point in practice (as opposed to just in theory)?

First, the investment might not be there.

Rational generation investors, that is, generation investors compelled by their shareholders and/or their fiduciary duties to earn a competitive return on capital invested, don’t invest where projected spot prices and related contract prices are inconsistent with their target returns. If the investment doesn’t proceed as assumed, then spot and contract prices are higher than they would have been.

Possibly, also, the risk of an earlier than projected exit from the market by large scale conventional generation is lower.

If we assume Australian renewable generation investors have similar targets for their investment returns on their portfolios to those recently announced by BP and Shell in pivoting to renewable energy, then the ISP’s threshold, the regulated return for network assets, falls well short of the acceptable rate.

In this sense, the ISP is circular:

it assumes the entry of generation consistent with the projected requirements without requiring the conditions on the ground to ensure that investment occurs.

Secondly, while no one’s making money on average, there are classes of generators that continue to earn higher than average spot market returns. In the current spot market, both conventional generation and batteries benefit from opportunities presented by interruptions to supply, regardless of the root cause of the interruption.

Although there’s still money to be made in specific well-defined and necessarily well-paid circumstances in the current market, the nature of the opportunity has changed, the incidence of high price events has fallen and the prices of caps and other options have fallen. As the composition of generation changes, these changes represent a deterrent to investment even for generation that might otherwise be expected to make money in providing services required by the electricity system.

Solving for the problem?

The additional markets being considered in the ESB’s market design are, I imagine, intended to address the replacement of the specialist services provided by conventional generation and the issues projected future spot prices present for specialist generators.

Specialised providers are, by definition, not your average intermittent renewable generator, but they might be diesel engines, gas, batteries, pumped hydro, other forms of storage or something entirely different.

Will new specialist markets provide enough money to tempt sufficient specialised production?

Don’t know right now and, on the ESB’s timeline, the answers are some time away. If the projections for renewable energy are correct, and the effect on spot prices follows, solutions emerging from the ESB’s design timeline may be too far away.

Changing the maximum and minimum price floors in the spot market and altering the conditions that trigger the Administered Price Cap, extending the period before the cap is applied, present an alternative, possibly cheaper and very probably quicker solution compared with the design and introduction of completely new markets.

Yes, there’s talking your book here, but there are other merits to working with what we have in preference to building more complexity into a range of markets. The Australian electricity market’s thin measured by actual and potential participant numbers. Specialist markets are likely to be thinner still.

The proponents of new markets need to be clear that the proposed markets can function efficiently, that is they clear efficiently, can support multiple participants with/out participation in the spot market, and prices over time tend to reveal costs, with participants earning over the longer term an appropriately risked rate of return only.

Is this likely?

There are projections of the performance of very fast response markets in the NEM, for example, that suggest that these markets are too thin to function efficiently:

one participant, very profitable; more than one participant, no one makes money.

These projections suggest that, even if a very fast response market successfully provides a service, it’s unlikely to do so efficiently.

If we don’t solve for the problem, what then?

If the outcomes of wholesale market won’t allow participating generators to make a sufficient total return in the absence of some external underwriting, then investors will look for that underwriting elsewhere before investing. (Long-term CFDs or PPAs are underwriting, even if they’re described as something else.)

When infrastructure investors and superannuation funds require long lived fixed price contracts in exchange for their proposed new renewable investments that’s a perfectly rational response to the situation all generators face. Something the Commonwealth Minister recognised when he said, in a recent interview ‘they would say that, wouldn’t they?’

It’s also a significant reallocation of the risks of providing electricity generation from private capital to electricity consumers and/or taxpayers more generally.

One of the successes of the introduction of the NEM was the substitution of private for public capital, without a requirement for the (citizens of the) state to guarantee returns to private capital in exchange for building electricity generation. We need to be conscious of what we’re doing in reverting to this state.

Why will consumers and taxpayers have to bear the risk?

The presentation I attended immediately after the ESB’s presentation advocated twenty-year contracts to underwrite renewable generation investments with the preferred counterparties, in rough order of preference, very large industrial users like smelters, governments, and finally retailers. (Ominously, retailers appeared to be an afterthought, prompted by a question from the audience.)

The number of potential private underwriting candidates isn’t large: say, generously, around a dozen significant private consumers at the right scale and perhaps a similar number of aggregated customer purchasing groups, and, similar again in number, investment grade retailers. Not enough candidates and not all of them investment grade credit, with 20-year time horizons or willing to agree to contracts that may lock in unattractive long-term outcomes, so an issue for investors, but also for electricity consumers and/or taxpayers in the transition.

Alternatively, despite renewable energy’s place in the cost curve, subsidy schemes like the RET etc. will move from being a bug to a feature, supplementing investor returns on a more-or-less permanent basis because intermittent renewables qualify for only some of the new markets to be introduced.

The promised reductions in customers’ prices will be eroded, however, unless, of course, the costs are passed to taxpayers. Given our experience to date, continuing subsidies with quantity and timing targets and funding limits probably continue the feast/famine cycle that’s such an issue for network planning and connections.

About our Guest Author

|

Patricia Boyce is a Director of Seed Advisory and has an extensive background in the energy sector. This includes roles in executive management positions in energy retail companies as well as a lead partner in a major international consultancy. Patricia has worked with clients including transmission and distribution companies, upstream and retail companies and with a range of government and regulatory bodies. |

Very nice analysis. The questions are heading in the right direction.

I’d ask a couple of them more directly:

– which VRE CfD purchasers are benefiting from very low wholesale prices

– if the market system is in crisis, then why are governments still forcing in new unnecessary supply using VRE offtakes – surely the government has some sort of obligation not to wreck the joint

– same goes for rooftop solar

The questions are good but as you point out everything depends on your reference point.

Mine is the need to decarbonise. If you start with that as the priority then policy will make the money be there. Same as for police or some other essential service.

The second observation is that there is committed and or under construction new investment sufficient to provide more than a further 10% of NEM energy. And I will offer 3:1 odds that there will be more commitments over the next few years. Yet without a policy to incentivise demand the total pie will not be big enough.

Here’s one of the things that jump out to me, Patricia, when I view that chart from the Renewable Integration Study:

https://wattclarity.com.au/articles/2020/10/wind-nemwide-lowpointtrend/

This post touches on so many issues its worth coming back to.

Whether people realise or not there is a big discussion about risk going on.

If revenue is guaranteed it is undeniable that the risk in financing wind and solar is very low, that’s because there is no exposure to fuel costs. Essentially your only risk is construction and breakdown. So then the cost of capital is low and the required price is low. But the risk has been shifted.

So the most fundamental principle of risk is it should be borne by those most able to price it appropriately. In many markets the private sector is the best placed to judge return and risk, that is a fundamental principle of capitalism.

Equally there are society level risks, such as say lung cancer from cigarettes, defence, a sufficiently educated population, that society has decided are best borne by the Government

The fundamental concern about risk is the need to judge the carbon priority. If there was a carbon price, a credible emissions trajectory, the risk of new investment could easily be judged by the private sector. Without that policy, the risk falls back to the Government(s) who signal their support for decarbonisation by providing PPAs without necessarily having to disclose their carbon policy. In this case the Government has better information than the private sector and may therefore be better placed to bear the risk.

There are other factors in that individual wind and solar farms are very small relative to the size of movement and also quite fast to build so that the risk of misjudging the total new supply required is smaller. Still it would be better done by setting a credible target and then letting the private sector work out how to do it. Its that lack of govt policy that is at the root of many of the problems.