On Tuesday last week I already posted these initial thoughts about some of the various ways in which COVID-19 will be impacting on Australia’s National Electricity Market.

That article contained several thoughts, including about the impact of coronavirus on electricity demand. Whilst I tried (in the 1st article) to make clear that this was probably not the most important impact, that question seems to have struck a chord, as a result of which some comment has been made in the FinReview on Thursday, on Friday and in Saturday’s print edition last week….

(A) Understanding the impact of Electricity Demand because of Coronavirus Measures

…. hence I thought it might be useful to take more of a look today, to the limit of time available.

(A1) Electricity Demand in the NEM

It seems much longer than just seven days since I posted these demand stats (last data for Monday 23rd March) – but that’s I guess that’s a boat we are all through this ‘coronavirus time’, where we struggle the ‘square the circle’ of headline stats that grow worse by the day, but also hear about plans of putting our economy into hibernation for 6 months or more.

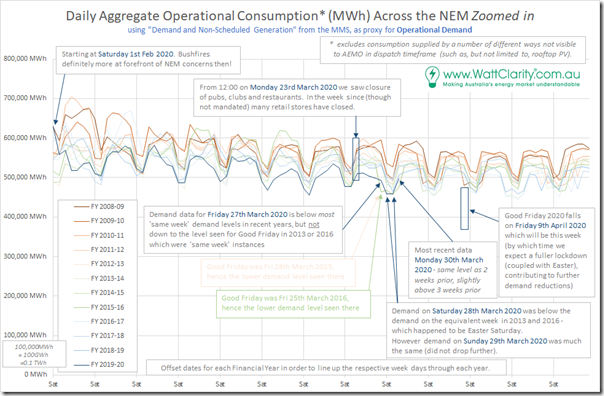

With that in mind I have updated the ‘zoomed in’ chart showing NEM-wide Operational Consumption on a ‘same day’ basis over the 12 most recent years:

The headline insight that could be gleaned from this comparison is that it’s quite difficult to see a clear impact from COVID response in energy consumption in the NEM (though that does not stop those with access to the data looking – like Bruce Mountain and Stephen Percy again today). There are a number of different factors at work, here including the following:

Caveat #1) This Operational Consumption metric* is influenced by many different factors independent of COVID response – including:

1a) the general shape of consumption (corresponding to season) and;

1b) the strength of consumption (due to weather patterns on that particular day and those immediately preceding), along with

1c) the strength of solar PV injections on the day and other ‘behind the meter’ injections from embedded generation of different types.

Whilst we would have hoped to have reduced the seasonal factor in the chart above (by showing only a few ‘same weeks’ each year) the other variables are still very present:

* Readers are reminded of this earlier (quite lengthy) explanation of some of the gory details of how electricity demand is measured in different ways in the NEM.

Caveat #2) For those comparing what’s happened in the NEM to what’s happening in other grids around the world (see below), it is also important to keep in mind that:

2a) In most cases, the seasons are different; and

2b) They may measure demand differently; and

2c) In many cases, the mix of energy users representing the aggregate are also different as well.

(i) Whilst a ‘rule of thumb’ might generally be a 33/33/33 split between residential, commercial and industrial energy use, it does vary quite markedly.

(ii) As noted back in August 2017, in the NEM the residential use of energy (in volumetric terms) is lower than this 33% assumed level.

> According to AEMO Forecasting Data for 2020, it’s roughly 24% excluding the residential share of losses .

> This higher proportion of C&I energy use as a historical artefact of what was the comparatively low cost of energy and availability of raw minerals, etc…

So whilst it might be an intellectual curiosity to try to see a pattern in the tea leaves (or in the electricity consumption data above) there’s a more important question we should be asking up-front, and that is ‘what do we think a good outcome should be?’.

The answer is not so clear to me as it appears to others. I will discuss this further in section (B) below, but first let’s take a quick tour of some other grids across the world….

(A2) Your armchair tour of other electricity grids (you’ll have to wait for it!)

For those who are interested in comparing the demand patterns in the grid underlying the Australian NEM and other electricity grids and markets around the world (notwithstanding the caveats above), I did start compiling a tabular list of all that I had seen from around the globe (there’s a fair bit!)

I started compiling this list, at least in part because I have seen an upswing in these kinds of stats over the past week or so – and to be a handy quick-reference I can refer back to at some future point in time. However I did not get this finished (even just with respect to what I have seen) – and so have removed it here and so will add it in as another article at some point.

(B) Broader thoughts about metrics that would actually be useful

Though the armchair tour above is certainly of interest to a data junkie like myself (particularly one who’s invested a career buried in the nuances of the electricity sector), I do at the same time wonder whether it’s actually that useful with particular respect to understanding coronavirus.

One of the reasons I chose to remove it (apart from running out of time) is that it risked being a distraction.

1) Fair enough that understanding where demand is tracking might be a key ingredient for you if your business is involved in direct supply of those MWh (if you are a generator, or a potential project developer) – or dependent on companies that are in the supply chain (such as ours); however

2) I am starting to wonder if these ‘how much has demand changed?’ questions are starting to take on proportions that are unrelated to their actual value – such as :

2a) being used as a direct proxy for the state of the economy (for which it might be useful, though not without the caveats above)

2b) being viewed as a weird proxy for the effectiveness of different coronavirus protection measures (which which it does not seem that useful).

Ultimately, I wonder whether it’s become another ‘buzz metric’ a bit like ‘electricity usage over Earth Hour’ was a decade or so ago, before realisation dawned that it was all a bit superficial.

(B1) The two key questions we need to be answering

To me, we should be starting by asking the following two far more important questions – in order to ensure we actually know where we should be heading.

Q1) What does success look like?

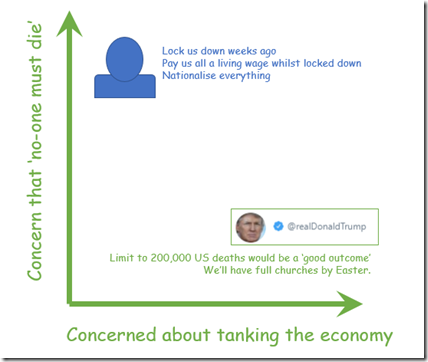

Strange as it might seem there seems to be a few different perspective on what ‘success’ means to different people. Without wanting to open up a detour down another rabbit hole, these seem to be loosely aligned on two axis which we might roughly label:

Axis 1 = ‘Noone must die’

Axis 2 = ‘We should not tank the economy’.

My point in mentioning this is not to pick ‘sides’ with respect to this question (I have personal views, but they are just that – personal). I am merely trying to point out that there seems to exist two clear axes, which different people are weighting in different proportions, but that both axes seem to be prevalent in almost everyone’s decision matrix….

Q2) How would we measure this success?

… hence it seems to me that we should be looking at metrics that, in combination, provide a view of our ‘success’ on both axes will be necessary for the vast majority of people (even if each individual chooses to weight each metric differently).

My hope would be that, by focusing our discussion around a small number of unambiguous, timely and actionable metrics, we can come to a much better collective understanding about the correct course of action to take.

A related question I have, though, is why it seems we’re doing such a poor job of this at present?

(B2) Metrics currently in use for Coronavirus Response

Important Caveat. I am not an epidemiologist (I had to look up how to spell that one) – and nor am I an economist. Hence please don’t misconstrue what follows as any advice on health, or the economy.

My background is of someone who has invested a career on using data to make decisions (most of the time in relation to the electricity market and systems). I write this out of concern that we might not be using metrics optimally in order to achieve “success” (however we agree that this is defined).

2nd Important Caveat. In addition the above, I may well be wrong in my conclusions and statements below (nothing new here – this is the case for all of my articles). If you think this is the case, feel free to leave a comment below.

In what I have seen in mainstream media, and on social media as well, the two main metrics that seem to be in use across the world in relation to the countries ‘success’ in addressing coronavirus seem to be the Number of Cases, and the Number of Deaths.

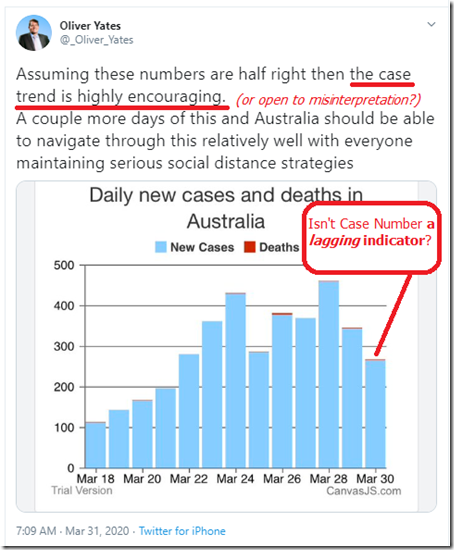

With apologies in advance for picking on Oliver Yates in highlighting the following tweet from earlier today, I thought it was a useful example to use to highlight what I see as some of the dangers in relying (perhaps too singularly) on just these two metrics:

Before I get onto these shortcomings, note that I am not advocating we stop talking about these numbers – just that we’d better understand their shortcomings, and add in other metrics that address these shortcomings and deal with them.

Shortcoming #1) They are lagging indicators – which detracts (further) from their actionability (see Shortcoming #4)

To me, the fact that they are lagging indicators is their gravest shortcoming.

(i) Regarding ‘Number of Cases’

I’m not sure of the exact science and stats on the time-lag, but I am certain that there will be one there – in between these five milestone dates in relation to the first metric ‘Number of Cases’:

DATE 1 = when someone becomes infected

DATE 2 = when someone first shows symptoms (if this is the case, as some can be asymptomatic apparently)

DATE 3 = when they manage to get tested (if this is the case, as we’re only gradually expanding our criteria for who gets a test)

DATE 4 = when their results are known

DATE 5 = when their results are added to this tally (remembering that the number of tallies on social media seems to be following its own exponential curve, so its almost certain that they have different timestamps).

Seems likely to me that the difference between DATE 5 and DATE 1 will be many days, and perhaps even a week or two.

(ii) Regarding ‘Number of Deaths’

Again repeating the caveat above, it also seems that there is an important lag also factors into the other metric, the ‘Number of Deaths’ (macabre as it might be to focus on). My understanding, based on what I have read from an eclectic mix of sources, is that this lag was initially not acknowledged, and may initially have factored into some policy decisions that – my understanding – are being unwound.

Specifically, my understanding is that the general progress of the disease, for those unfortunate enough to catch a big dose of it, is such that:

DATE 6 = some short time after diagnosis, there is a spike in elderly patients (and those with other risk factors) succumbing to the disease; but also that

DATE 7 = some time later (perhaps a week or more) younger people can also succumb, after the virus takes its course – especially exacerbated by availability of ICU space and the like.

Hence the ‘mortality rate by age’ stats that are built by DATE 6 are likely to under-represent the severity that this disease might have for younger people, and might contribute (though not wholly explain) the ‘bullet proof’ mindset that has been on display in various clips of young people in the media.

——————

My perspective here is not about the science of disease (of which I am no expert), it’s more about the challenges in using data properly to make decisions …. and to help others make the ‘right’ decisions as well. That’s the underlying challenge we have based our business around – albeit in a completely different domain to coronavirus.

However Shortcoming 1A (that they are lagging) seems to be compounded by the fact that this is often overlooked (let’s call that Shortcoming 1B). It does not seem remotely credible that ‘we’ (being an individual, an organisation, or a Government) could look at some change in these metrics and use that to judge the success (or not) of various decisions that are made on essentially the same – or shorter – timescale.

This would be akin to driving a high speed car by looking in the rear view mirror. We should all intuitively understand how difficult this would be to do – why is it, then, that not many people at all seem to be flagging this as a most serious issue in how we are responding to coronavirus?

Shortcoming #2) The Metrics (esp ‘Number of Cases’) are prone to selection bias

In simple terms, if we don’t test someone, we won’t know if they are positive or negative. I understand that there are many who are advocating a ‘test, test, test’ methodology – and I can understand the reasoning behind it.

However that is not the reason why I raise this here.

In the real world there are other constraints that we need to deal with (whether they be via political screw-up or not), as does every other location we might be wanting to compare stats against. Hence we better be very clear about the possible margin for error (flowing from selection bias) as a result of these when thinking about, and then speaking about, the results.

Shortcoming #3) The Metrics are aggregates of different components

Others chiming in on Oliver’s comment on twitter have highlighted one other significant snag in his logic, where he moves from lagging indicators of ‘Number of Cases’ to the presumption that, he thinks:

‘A couple more days of this and Australia should be able to navigate through this relatively well with everyone maintaining serious social distance strategies’

As others have noted, to date the number of cases being recorded in Australia has been skewed by the number of cases showing up in overseas arrivals (with the debacle of the Ruby Princess being the most obvious example of how we did not stop the boats (or the planes) soon enough).

Rather than venture further down that rabbit hole* I would like to use this example to highlight how the headline metric (aggregate ‘Number of Cases’) masks the component metric we should be most focused on – ‘Number of Cases by Community Transmission’ keeping in mind that we magnify the selection bias in trying to look at this because we have, until recently, focused on overseas arrivals as one of the criteria in determining whether to be tested or not.

* My sense is that this is a rabbit hole because the Ruby Princess horse has bolted, but it would appear that the gate is being closed – too late, but still necessarily. For instance:

(i) I presume (but have not seen stats) that returning visitor numbers should be declining; and

(ii) The country has changed the way in which the cruise ships are dealt with (e.g. in WA), and

(iii) because confinement for overseas arrivals is now being enforced.

Perhaps more importantly, there’s also an element of ‘there’s nothing I can do about foreign arrivals’ which means those stats should be de-emphasised in daily reporting if the objective of the reporting is to facilitate people making certain behavioural decisions (which surely it needs to be?!).

With Community Transmission as a focus, we need to recognise that the stats highlighted in the tweet above are misleading:

1) It may be that there’d be a completely different picture emerging if we were looking just at a trend in Number of Cases confirmed to be by Community Transmission inside the country; but

2) This consideration seems to have completely been missed by Oliver in his conclusion. Again, I’m not meaning to pick on Oliver in particular – but rather to flag that Oliver is a smart guy and still seems to have made the error in his leap in logic to his conclusion. How many others are going to be drawing the wrong conclusions because we are focused too much on the ‘wrong’ metrics?

Shortcoming #4) The Metrics are not very actionable

Last in the list of shortcomings I’ll talk about today (there are some others, but don’t want to distract) is that both of the measures are not very actionable.

In essence, even if it were possible to be driving our high-speed sports car by watching the rear view mirror, how would you know which way to steer, if all you could see (looking backwards) was what your speed was, and how many speeding tickets you had accumulated?

We need at least some of the metrics we focus on to be actionable – at all levels of society (for the whole country, and down to us as individuals).

The low-tech egg-timer for the shower during the millennium drought was something that seen to be effective in this respect by focusing people on ‘what can I do, personally?’.

We need the equivalent for our own battle against coronavirus – both for the society, and for us as individuals. What metrics can we be provided with to help us understand if (collectively) we are ‘playing our role’

———-

Thinking back about the electricity market for a second, I’d link in a relevant example from our own experience. Many readers would understand that we’ve been a keen developer and supplier behind ‘the RenewEconomy-sponsored NEMwatch Widget’ for many years, which is:

1) here on the RenewEconomy site; and

2) here on the NEMwatch portal; and

3) here on this WattClarity site; and

4) in many different places – the number continues to grow (it’s no charge to embed).

One of the reasons why we have appreciated the opportunity to provide this service in conjunction with RenewEconomy to thousands of people has been because it’s helped people understand some of the inherent challenges in making the transition from the electricity system in the past to one of the future.

In doing this, we have deliberately focused on actionable or meaningful metrics – being rate of production (i.e. MW) from different fuel sources (and MWh and MW.s (discussed here) and so on…).

We have not, despite any number of different requests from users of the widget, added in percentages in the mix as (in my view) they would essentially just be Vanity Metrics that are Not Actionable and won’t deliver the increased understanding necessary to help this energy transition succeed.

———-

(B3) So how does Electricity Demand fit into the above decision-making framework?

Having worked through the above, I would have to say my headline response to this question is that Electricity Demand is probably pretty poor as a headline metric to be focused on – hence my concern, noted above, that it’s at risk of being misunderstood, and misused.

Q1) How does a change in electricity demand relate to success (or otherwise) of fighting coronavirus?

Very poorly, seems to be the case here. To use electricity demand in this way seems akin to the tale of the man searching for dropped keys under his porchlight (where he can see), despite the fact that he dropped them over there in the bushes (where it is dark).

Q2) How does a change in electricity demand relate to change in the economy?

One strength of this approach is that it is more ‘real time’ in measurement than the more formal (but very laggy) indicators of economic activity.

However it is also still quite prone to misinterpretation (because of seasonal impacts, and impact of ambient temperature, and rooftop PV substitution, and so on). Whilst these might be able to be backed-out, these processes would necessarily be complex and ‘black box’ to an outside observer.

Hence in summary I wonder if there are not better metrics – or at least metrics that could be used in conjunction with electricity demand to see a fuller picture.

(B4) So what metrics could we be using?

It’s clear that we’re battling two different – but related – crises.

Firstly, we have the immediate crisis of coronavirus and the impact this is having on the health system more broadly, but also individual’s health more specifically.

We also have an economic crisis which could quite easily cascade into its own crisis of public health and well-being (though perhaps affecting not quite the same people).

Matthew Cranston made a commendable effort in putting together his ‘six charts showing an economy going into hibernation’ article in the print version of the AFR last Saturday (tweet is here) – and it is understandable that the Fin Review has a focus more on the side of the economic crisis.

However that’s only half of the story – and perhaps not the most important half, on a whole-of-society basis in the next few weeks. I’m wondering whether the insights we have gained in identifying and using performance metrics in the electricity domain might prove more broadly useful in battling the immediate crisis in public and private health – hence wandering on a fair tangent in this article…. (readers can tell me if this has been useful, or not).

No matter what the metrics we use, we should be seeking that they satisfy the following criteria:

Criteria #1 = that they are as clear, and unambiguous, as possible

This is one place where Electricity Demand falls down – even in the industry, we trip over ourselves because have many different ways of measuring it!

More recently, the AEMO is favouring the use of ‘Operational Demand’ as a measure. I can understand where this favouritism is coming from but also see some significant draw-backs:

Drawback 1 = AEMO has not published much history of this measure, formally

Drawback 2 = Even to the extent we have history, I’m concerned that it’s not apples-for-apples comparison of how Operational Demand has trended, as the aggregation function changes as new Non-Scheduled generation are added in (e.g. one day Rocky Point sugar was not there, one day it was – same for Royalla Solar Farm and so on). This sort of thing has weighed into industry submissions on rule changes, for instance – especially in dealing with AEMO’s forecasts with subtle changes in methodology year-on-year.

Criteria #2 = the metric should provide real-time feedback, relevant to the particular decision we are making (or decision we are imposing).

No more driving with an eye on the rear-view mirror!

Criteria #3 = the metric should be actionable.

If the number is better (or worse) it should be clear what ‘we’ (i.e. whoever the intended audience is) need to do in response to the change in the numbers. Not much point measuring something if you don’t know what you will do in managing following numbers becoming worse (or, we hope, better).

(B5) Brainstorming possible metrics

It’s late, and I need to finish this off tonight to get back to our real business of keeping our customers happy through the software they licence for us in the electricity market – so what follows is a bit of a brain dump of possibilities….

B5a) Metrics focused on the Public Health Crisis

I note that the Australian Government has (very belatedly) got off its arse to produce some tools for the general public to use in protecting themselves and (at the same time) reducing the rates of community transmission. Also read somewhere, I think, that Atlassian (Australian success story – pity they shifted corporate office to avoid paying company tax in future, though that’s another story) has been helping with some of this.

I’ve installed the App, but would not touch WhatsApp (or anything by Facebook) as their reputation precedes them.

Unfortunately the app has a distinct lack of ‘actionable metrics’ that the the general public might actually use to help deliver what we all need – in terms of reduced community transmission in the shortest possible time.

Hence I (like I suspect many others) might have already consigned the App into the ‘not much practical use’ mental model, from where it will progress to the ’delete’ bucket if the information updates continue to be not that useful to an individual Joe Public (especially of there is any hint at a Smirk in the message).

It makes me wonder, if the objective would be to message directly to individuals about what they can do, personally, to do what we understand are the key personal steps:

Step 1) Wash hands frequently

Step 2) Severely limit physical interactions (but not social interactions – albeit virtual, to protect mental well-being).

On this front, I have seen the ‘City Mapper’ service referenced to me by an increasing number of people, so it would seem to have some of the underlying fundamentals working. Though for me it’s still pretty opaque (in terms of what it actually measures) and is not that actionable (in terms of what a person could do to actually turn the dial).

However perhaps we could start with a concept like this and make it more relate to something an individual can actually relate to.

Alternative #1) One example might be some form of metric like ‘average person meters travelled today’. This would need some form of access to smart phone geolocation services – for which we’d be looking at three different options, I guess:

Alternative 1a = the carriers themselves (with Telstra still the largest mobile carrier, I think, top of the list of possibilities);

Alternative 1b = the OS providers (with Android having more handsets than Apple, but both probably being representative enough:

(i) how about it Sergey/Larry something actually useful for Alphabet to do beyond just count your advertising cashflow?

(ii) or you, Tim, something you could actually hang your legacy on – not just bigger and flasher phones?

Alternative 1c = some ubiquitous platform provider that is installed on everyone’s phone and harvests up everyone’s usage data anyway (looking at you, Mark).

Other options here, for underlying metrics (if phone mobility data is unavailable) might be:

Alternative #2) Some form of “In-store shopping visits” (i.e. excluding online and groceries) which might be obtained from EFTPOS via the banks, or just aggregate across the big store brands. How many jigsaw puzzles does a person need!

Alternative #3) Volume of petrol sold, particularly in the hot-spot locations of Sydney, Melbourne, and South-East Queensland (though this would not exactly be a real-time measure of mobility).

Alternative #4) Public transport trips taken in a day (i.e. tallying across GoCard, Myki and Opal for a start). Should be manageable to extract.

Step 3) Propagate the message; and

Step 4) Avoid passing it on (see 1 and 2), and seek help, if sick

For the global tech ‘platform’ companies whose names are mud (you know who I am talking about) I am wondering why they are not seeing this as a crying need to utilise their smart technical resources and devote the oodles of talent they have to creating some form of global app that will actually make a real beneficial difference in the world. It might start to win them back some of their foolishly lost brand equity – because the alternative seems to end up with Anti-Trust cases and company breakup somewhere down the track.

With all the smarts they have at their disposal, add in a bit of ‘gamification’ and we might actually have different locations (be they suburbs, cities or countries) constructively ‘compete’ with each other to try to better each other in each of the steps above and hence beat this virus.

B5b) Metrics focused on the Economic Crisis

As noted above, seems to me that the AFR made a good start in putting together their ‘six charts showing an economy going into hibernation’ article in the print version of the AFR last Saturday on this front, and I will look forward to sharing other ideas directly with them as they occur to me.

…. but that’s all I have time for, tonight!

Leave a comment