It is curious that despite of the findings of the recent ACCC enquiries and the on-going regulatory uncertainty (at both a state and federal level), anyone would be willing to set-up an electricity retailer.

New venturers in the energy market could be forgiven for thinking that running a successful energy retail business is as simple as having the right processes, systems and marketing tools; that a retailer is only a “billing agent”.

In this context, energy retailers – as with any intermediary business – need treasury to fund the time lag between when they purchase goods on the wholesale market (energy from the NEM at spot price) and when they get paid by their customers. The introduction of smart meters, particularly in Victoria, has allowed a shortening of this timeframe and with it, a reduction in the requirement for treasury funding.

New energy retailers tend to focus on the marketing aspect of the business, and can end up ignoring or overlooking the procurement component and the significant funding it requires.

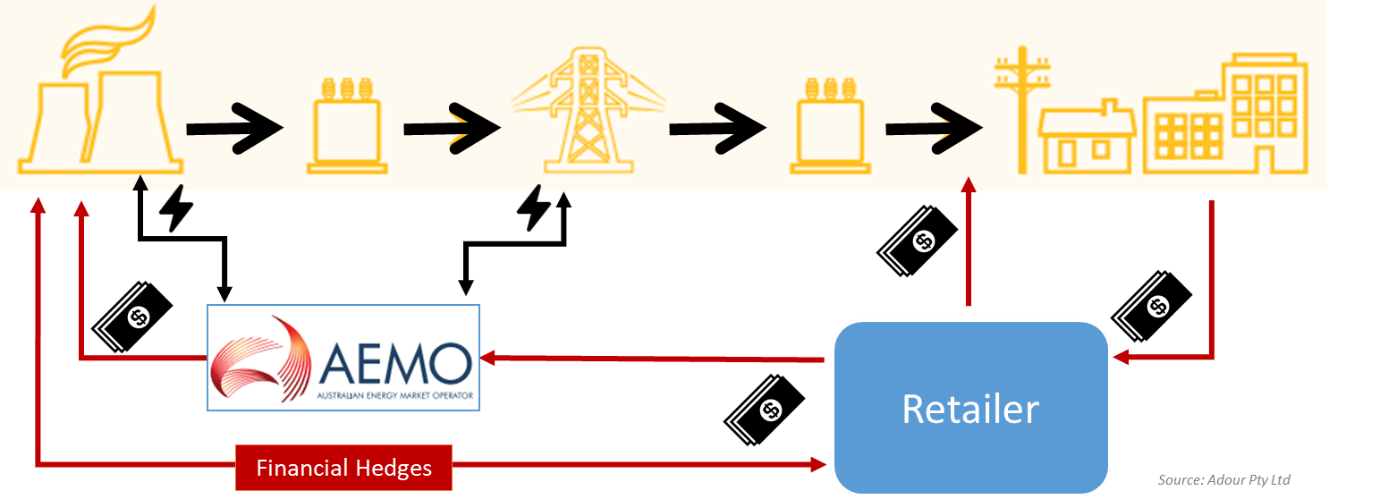

Let me explain: from the end-user/customer perspective, the retailer may well be a billing agent; but from the wholesale market perspective it is a “credit agent”. One key role of the retailer is to collect (and chase) the money from customers, and redistribute it to faceless market participants: network, AEMO, hedge providers…

The below graph schematises the “electron” flow (from generators through networks to end-users – in black) and the “money” flow (from end-users, through retailers to “wholesale” operators – in red).

While the retailer is remote from the physical aspect (electron) it is the sole customer facing body when it comes to money collection. The networks, AEMO, the generators and the hedge providers all depend on the retailer to get paid for the energy they produce, transport or hedge.

This role is defined under the NER (National Electricity Rules) as the Financially Responsible Market Participant (FRMP), with following responsibilities:

- Timely and accurately invoicing of customers

- Collection of money from end-users

- Payment to networks for access and usage

- Payment to market for energy usage (AEMO), who in turn will pay the generators

- Settlement of energy hedges (positive or negative cash flow)

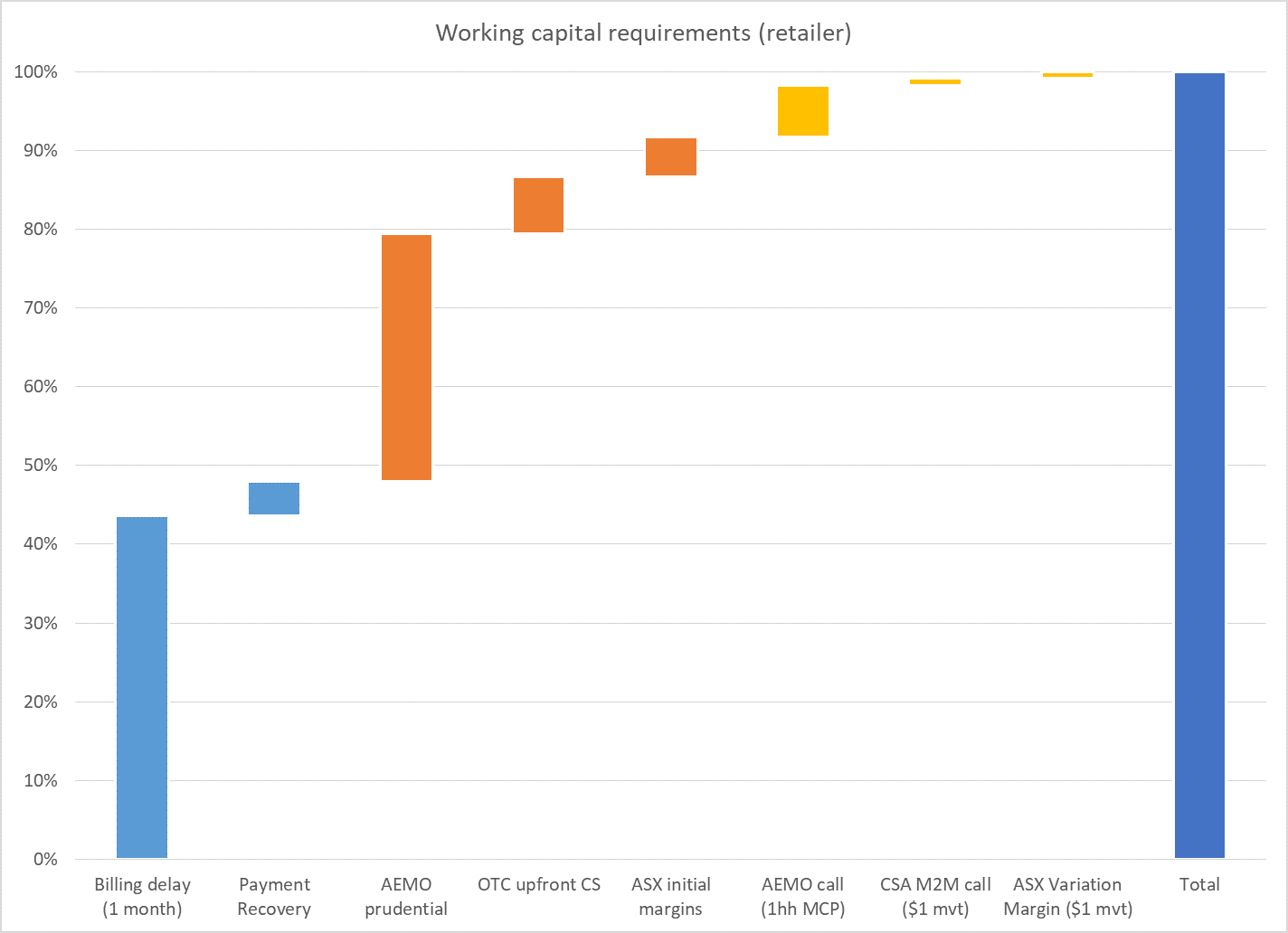

As per these responsibilities, the retailer must provide credit support or a financial guarantee to protect its creditors in event of default. As such, the energy procurement/hedging function is working capital hungry.

- AEMO must ensure the NEM is whole from a settlement perspective and there is no payment shortfall. Each debtor (mostly retailers) must post and maintain prudential, reflective of their level of exposure and potential outstanding. It is important to note that generators are rarely required to lodge prudential, being creditors to the NEM.

- Network operators may at times require credit support from retailers (depending on credit profile).

- Likewise, hedge counterparts may rely on the ISDA’s Credit Support Annex, to obtain credit support from lesser creditworthy counterparts.

- The ASX, like the NEM, must always be whole from a settlement. So, like AEMO, the ASX (or the clearers) require initial margins for each trade/hedge executed on the exchange (buy or sell).

Further, those trading counterparts may call for additional credit support during volatile price periods to offset an increase of outstanding, adverse change in mark-to-market positions or a degradation of the credit risk profile.

AEMO and the ASX monitor outstanding/Market-to-Market position of participants daily. Volatile market conditions, price spikes (MPC) may trigger a “margin call” (most likely in the form of cash) which must be responded to overnight, even though it may ultimately have a negligible impact at settlement.

The most common forms of credit support are bank guarantees or cash. The retailer must ensure it has access to liquid and immediately accessible working capital to respond to such calls. Failure to do so will trigger market operators (ASX and/or AEMO) to close position and deregister the failing party, often triggering cascading events toward administration.

The NEM’s history is littered with examples of retailers carrying a positive balance sheet but defaulting because they were unable meet their credit support requirements.

Late in 2009, NSW based retailer Jack Green failed to pay a $0.5m bill to NSW network operator Integral. It immediately triggered a suspension by AEMO, followed by a revocation of its retail licence, culminating in the company going into administration. According to the receivers, Jack Green owed $11m to major creditors (hedge providers, network and AEMO) while the accounts showed up to $25m of unpaid bills by customers[1].

More recently, Go Energy suffered the same fate, unable to fund increasing AEMO prudential resulting from the seasonal growth of its customer demand (+40%) combined with high spot prices during January 2016.

Credit support, collateral or prudential are not new concepts. In the financial sector, the APRA regime compels banks to hold sufficient reserves to reflect their liabilities. Recently the banks invoked those increasing requirements to justify the raising of interest rates – a luxury that energy retailers are not afforded despite an increasing need for working capital driven by higher prices, higher volatility, higher funding costs (ref. interest rate above), higher compliance costs and a more favourable customer protection regime.

Despite the name, “working” capital is not productive. Cash or bank guarantees attract hefty drawing costs and generate little interest. It is difficult to explain to any willing investor that part of their money will be “sleeping” on the account of the counterpart – not contributing to incremental revenue.

Unfortunately, retailers have a limited number of options to mitigate these working capital requirements and associated costs.

The AEMO settlement process includes a “reallocation” mechanism which allows one participant to allocate a “trading amount” to another. The participant will be credited with that trading amount, reducing its outstandings and prudential liability toward AEMO. Conversely, the participant offering the re-allocation is liable for that trading amount and is taking a credit risk against the benefiting party. Reallocations can be treated as “short term lending”; providers will usually charge a fee for service and require some form of collateral or credit support to protect their position.

Retailers can hardly pass those imposts to their customers, despite being “Financially Responsible” on their behalf. Customer credit assessment is limited and they benefit from a protective regime in terms of delayed/default payment, which renders the recovery process lengthy and costly, and ultimately in excess of the value of the debt. In cases where the retailer is forced to write off a customer’s non-recoverable debt, it has no recourse or access to credit support to mitigate its net loss, unlike market participants further up the supply chain.

For example, hedge contracts typically attract credit support of around 10% of face value. Applying this figure to the annual average electricity bill, can energy retailers ask their customers a bond of $150 when they join? I thought not …

[1] https://www.smh.com.au/business/jackgreen-funds-unlikely-to-reach-power-companies-20100103-lnan.html

About our Guest Author

|

|

Tiburce Blanchy is the director of Adour – Energy advisory. A creative and solution-focused adviser he helps companies develop their hedging and commercial strategy to support business growth, before translating it into effective operations. With 20 years experience of energy markets in Europe and in Australia, he has a deep knowledge of hedging and risk management, along with demonstrable expertise in energy derivatives, renewable and carbon schemes, and international oil and gas markets. Tiburce Blanchy holds a Master Degree in Mathematics and Financial Markets. You can find Tiburce on LinkedIn here. |

Be the first to comment on "Retail Energy, not so easy"