Back in mid-2010, I did start to put together this synopsis of opportunities and threats for (major) energy users – however, as you’ll note from that article, it was never finished.

In particular, one of the areas in which I did not have time to focus (and write) is in relation to network costs, which have grown since the start of the NEM to represent a larger percentage share of the total cost of electricity delivered in the NEM – whilst wholesale unit energy costs have remained largely the same ($/MWh) over the same period.

In the intervening years, the “network debate” has increased in volume and (at least it seems to me) the complexity of the positions on all sides. I have tried below to relate my current understanding of the key elements under debate, in the hope that:

(a) Others, who are more knowledgeable in this area, can fill in some gaps; and

(b) These starting notes (plus comments from more learned experts) might assist others who are also striving to understand what the debate’s all about.

PLEASE NOTE

In the discussion below, WattClarity ® Readers should note that reference to external material should not be taken as support (or otherwise) of any particular point of view. Rather, this post is provided to indicate the current state of my understanding of various perspectives in the debate – and, as such, might help others also seeking to understand.

From the outside-looking-in, its seemed to me that the points of contention seem to fall into four categories as noted below:

1) Underlying boom/bust cycle

With my career having been based in the energy sector, and now into its third decade, I’ve watched with interest what’s seemed to be an underlying boom/bust cycle that has seemed to sit beneath much of the results more apparent at the surface. My sense has been reinforced by tales told to me of older/wiser people who have been in the industry longer than I, and can remember the day when… etc

The pattern has seemed to go like this:

(a) Some scarcity event occurs – in which case the signal is sent to the Engineers to build, build, build. This signal might be sent through a market price, or might be sent more explicitly by a “the lights shall stay on” responsible Minister, or through some other means.

If this boom stage is pronounced, then new metrics start to emerge that seem to take on a life all their own – such as “build rate”. The use of such metrics seems to shift focus away from the original reason for the build and the need to build takes on a life all its own.

For instance, the Queensland region of the NEM was under-supplied right at the start of the NEM – and, following from that state, we had the commissioning of QNI plus 2,000MW of capacity at Callide C, Millmerran and Tarong North in relatively quick succession. Naturally spot prices fell, as a result (given a competitive market).

(b) Then one day someone will realise that the cost of this supply has increased significantly (a customer, if on the regulated side), or profitability has fallen (a shareholder, on the market side) and the engineers will be reigned in. It becomes the Era of the Accountant whose mantra seems to be (in simple terms) running existing assets as hard as possible to generate higher utilisations and more effective returns.

Over this period, a different set of KPIs are put in place – and, in some cases, also begin to take on a significance all their own – just like metrics such as “build rate” in days of yesteryear, they take on a meaning that becomes more and more separated from their original reason for being.

What’s happening in global Iron Ore seems very similar, where a “stronger for longer” mantra has given way to a focus on slashing costs.

(c) Everything seems to run swimmingly until something happens and the system that’s been gaffer taped together starts to spring a leak somewhere, which signals the Return of the Engineer – and so on it goes in cycles….

We’ve seen that these cycles are sometimes “helped” on their boom/bust way by aggressive (poorly thought-through?) government policy – such as noted by Nigel in relation to the ongoing SolarCoaster.

Just today I noticed this post from TransGrid, which seems to strive to make the trade-off between investment and reliability more transparent (and the decision more explicit).

This oscillation around an underlying growth trend (at least up until 2008 or thereabouts) also seems to have parallels in other industries and with particular companies, and I have sometimes wondered whether it has to be that way – i.e. is it really possible to continue to have a dual focus on growth, and efficiency at the same time?

Perhaps the ability to properly manage both challenges simultaneously is what sets the well-managed companies (and industries) apart.

2) How much to invest (or has been invested)

Within the context of this underlying boom/bust paradigm we’ve seen an unprecedented change in the NEM, as in established electricity sectors across the world, in that demand has been declining in recent years.

Whilst the rising tide might float all boats, the fact that the tide has gone out has exposed the fact that the industry has, to some extent, been swimming naked. This has, it seems, significantly compounded this aspect of “the network debate”.

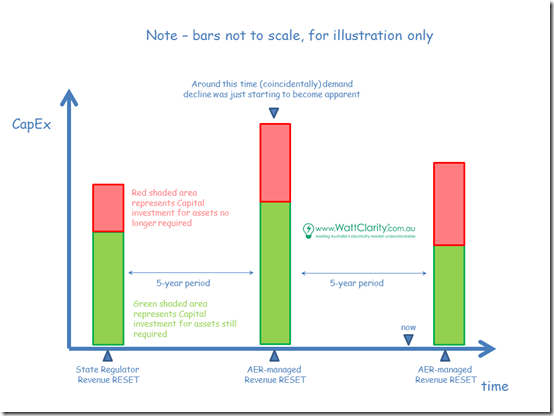

Graphically, my understanding of this part of the debate can be summed up in the following graphic:

Currently, we’re beginning to see what I think is the second round of regulatory decisions being made by the AER on allowable capital investment on the part of each of the NSPs (transmission and distribution companies).

I believe that these are showing lower levels of capital allowed than was the case 5 years prior – but I have not had time to check where these levels are with respect to the levels allowed 10 years ago.

2a) How much WAS invested

One of the reasons why network costs have increased is because of increased capital allowances conveyed through periodic regulatory “Revenue Reset” decisions for the network businesses.

For the middle period in question (shown in the illustration above) there was much mention made of two factors justifying an increase in capital spend:

1. There was much talk of growing peak demand. Whilst hindsight is truly a wonderful thing, and does present the “what were they thinking?!” question after the fact, I remind myself what I wrote here on WattClarity in mid 2009 (i.e. around the time of that regulatory decision) illustrating that I was certainly not wiser than those producing load growth projections at the time.

2. There was also much talk about replacement of ageing infrastructure. I’m not sure where this process is at.

Summing this all up, there is a sense that some of this capital was for assets that (in the “declining demand” paradigm) are no longer required – i.e. the red bars above. If the NEM was operating in an environment whereby demand was continuing to increase, then it might just be a matter of time before demand “caught up” to network capacity – but now there are open questions about whether some capacity will ever be needed (or at least, from an economic point of view, needed within a timeframe to make the investment seem reasonable).

This is the bit that some have called this “gold plating” (though perhaps, by some interpretations, this is not so accurate/helpful a term).

Whatever the cause, what seems to be the eventual end-result of this component is that some of the “overcapitalised” asset value will (sooner or later) be written off. I can see different arguments for who might bear the cost of such a write-off:

1. It might be the asset owner (hence shareholders), on the basis that they had built more than was required (and were involved in the generation of the load growth projections used to support the CapEx in the first place). However such a decision would not be without concerns of long-term effects due to changed perceptions of sovereign/regulatory risk (i.e. an outcome of “changing the rules of the game”)

2. It might be the government (hence the taxpayer), on the basis that they put the rules in place that produced this current result. Not without a political cost, and loads of finger pointing, as “wasn’t me!” politicians are prone to do.

3. It might be the customer that ends up carrying the can (hence with a bias towards big energy users) on the basis that they will be the ones that squeal the least. Another concern of energy users!

See my prior notes about the problematic nature of a capacity market on the energy side.

Here’s Bruce Mountain’s view of write-downs as a way to address stranded assets in electricity networks. A different perspective is provided in this paper by the Energy Networks Association. Here’s some other commentary by Keith Orchison, and another from Joe Dimasi.

2b) How much is TO BE invested in future

Much has also been written, in the past couple years, about a “Death Spiral” – one of the first mentions I can recall was this paper by the AGL paid or Simshauser and Nelson in mid 2012.

Whether or not such a calamitous outcome arises remains to be seen (as it will be dependent, in part on questions such as those following). However it does serve to illustrate the fundamental challenge of a regulatory regime which effectively locks in Capital Investment up to 7 years in advance in an environment where future load trajectory, and hence need for the network, seems much less certain than was the case 10 years ago.

Surely there’s a better (i.e. more incremental) approach – however such an approach would not be without its own incremental costs, including:

1. Probable higher overhead costs of compliance, required at the NSP and the regulator as a result of a more continuous stream of data flowing backwards and forwards; and

2. Unavailability of volume discounts on “bulk purchase” of certain kinds of equipment that is a sound approach if demand is more predictable, but more risky if demand is uncertain.

3) What rate of return is allowed

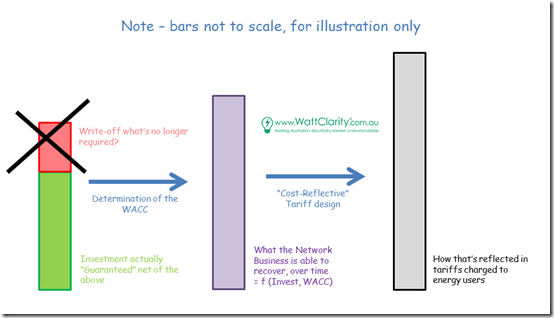

Let’s assume that we’re just talking about the green bars above (i.e. that through some magic wand or other economic tool we’ve managed to deal with the over-investment in the red bars above).

3a) Allowable return

There still remains an issue, which has become increasingly debated, about what a “fair” return should be for “allowable” capital spend on the networks.

The theory goes that the network businesses are lower risk (i.e. monopoly supplier, so guaranteed a return), so should receive a lower return than would be the return achieved by companies operating in a competitive market.

What seems simple in theory appears to me, from the outside-looking-in at the debate, much more complex in practice – as it evolves to all the letters/variables and arcane acronyms that go to calculating a company’s allowable WACC (Weighted Average Cost of Capital).

This Grattan Institute report from 2012 is one of a number I have noticed on the topic.

There was a diagram published in the past week or two (that I can’t find now) which highlighted actual returns of network businesses (I think by Return on Equity) compared with others in the competitive sector that purported to show that the network businesses were achieving higher-than-necessary returns. If I find it later (or one of our readers points it out) I will link it here.

3b) How much actually is recovered

Notwithstanding the discussion point above, there seems to be another issue that (at least in my reading) does not seem to have gained as much focus – that of how much of this return is actually being recovered (in real cash in the bank), if volumes are declining?

I think the theory goes like this – the AER allows a return (i.e. total $$) which the network business then translates into some kind of tariff (predominantly $/kWh at present – see below) at which point two things might happen:

1. From an accounting point of view, this revenue (being “guaranteed”) might be able to recognised in the books.

2. However if volumes decline, then this might lead to an under-recovery. Hence the books might show X whilst the bank balance shows Y (where Y < X).

If the revenue is truly “guaranteed” then the problem might just be a timing issue, in terms of recovery of revenue – but what happens if the demand does continue to decline, and the gap between X and Y widens over time?

4) How these allowable revenues are charged to energy users

So let’s assume that we’ve worked out a “fair” amount of investment, and a “fair” return for the network businesses. I’m coming to realise that this does not mean we’re out of the woods yet – as illustrated here:

4a) What the network business charges

The AEMC passed a rule change, effective from 1st December 2014, requiring network companies to structure network tariffs on a “Cost-Reflective” basis (here’s the press release, and here’s the details).

Again, what seems to be simple at first glance, but appear to be a lot more convoluted in practice. I have not had time to read through the background material the AEMC has helpfully provided yet (so it’s my fault if the following is misguided) so I do wonder “what costs?”.

Are we talking about recovering past investment (i.e. sunk cost), or are we talking about sending price signals to incentivise future behaviour to optimise future costs? I’m not sure these are the same things (perhaps readers can help me understand)?

Already there seems to have a couple different approaches emerge to the implementation of cost-reflectivity amongst the network businesses. There has been much written about the effect these mooted changes will have on various types of stakeholder in the electricity sector, such as on Monday in the FinReview – and many more bytes of space in focused publications like RenewEconomy (plenty of comments) and Climate Spectator + discussions at many events such as this CEDA event and this ENA event I was unfortunately unable to attend.

This whole debate seems to have become significantly more clouded through the emergence of a significant number of vested interests across the industry, and a splintered (survival-focused) political narrative.

4b) What the energy user sees

Even if the distribution company could determine the “perfect” tariff structures, the effect of these would probably be obscured through the fact that it’s the retailer that bills us as consumers, not the network company directly. This might be especially the case for those retailers still struggling with billing system issues.

Are we, as part of this industry transition, going to see the evolution to the point whereby we start receiving 2 (unbundled) bills for electricity:

1. A “grid connection” invoice from our network company – which might be more akin to our monthly fixed price charge for internet connection (where it’s my understanding that the costs are almost solely related to the infrastructure we connect to) for those of us who don’t “snip the wire”; and

2. A separate “energy supply” invoice from our retailer – for those of us who don’t wholly supply (matching our consumption profile with self-generation each five minutes of every different day, in all weather conditions) ourselves with self-generation + storage.

Whilst the network company might incur added costs in the provision of individual bills to each customer, perhaps the benefits delivered in terms of real response to peak network events (which Chris Dunstan alluded to here, and which we’d like to provide more focus to on our new site here) would more than cover these added cost – and put us on a path to a more sustainable future.

That’s all I have time for today… (but I will be very interested when more learned people than I can help fill in the blanks, and correct the errors, in the above).

You’re still a young fellow Paul!

Moving through my fourth decade in the industry…, I see new energy technologies and energy market uncertainty compelling both residential and business consumers to respond by taking increasing control of their own destiny. In doing this these consumers become, what we call ”Proactive-Consumers” or “Prosumers”.

We see this evolution every day. Over the past 8 years our company focus has been on helping businesses enter contracts for grid supplied energy and arranging the best available network tariff, but of late our business is increasingly about helping businesses run the maths over alternative energy supplies, solar PV, battery storage, negotiating energy buy back agreements and in some cases designing and costing complete grid disconnection.

Even in Tassie roof top solar now amounts to over 80MW installed capacity, so consumers have invested probably $150M over the past 10 years. This tells us consumers are taking increasing interest in, and control of, their energy choices. Therefore overtime the traditional energy supply business model and political intervention will increasingly loose, or at least drastically change, in its ability to influence consumers.

When we discuss Network tariff reforms or investment in more centralised generation, we also can’t help but wonder if some incumbent businesses are planning for future scenarios which may not ever materialise. The challenge we think is rather to describe likely future scenarios and then plan around these alternative futures.

Cheers

Marc

Only in my second decade in and around the NEM, but have also seen the same cycles. The basic problem is that the NEW capex is set at the start of the process based on forecast demand… and forecasts are always wrong. Having agreed that an investment is “required” the regulator can’t very well turn around and say “oops sorry, we were all wrong and now you don’t get to make a return on that capital”. On the other side, regulated prices are intended to prevent networks exercising monopoly power in setting prices. I think it is a fair trade off to allow networks to recover a a “fair” return on those “good faith” investments that all sides have agreed are likely to be needed. Yes if it was a “real” market the investment would be stranded and not earn a return, but on the other side if left to that same market, network providers would address that stranding risk by shortening the payback period on that capital expenditure – resulting in higher network charges anyway. You essentially can’t argue for regulated cap to protect consumers on one side and then argue against that same regulatory system protecting the return on capital for the investor on the other. Benefit sharing is as good a mechanism to “correct” these forecast errors as they become evident, as the operator is incentivised to not spend capex/opex they don’t require as that (lack of) need becomes apparent.

Great article Paul! I think the ROE diagram you were looking for is here: http://www.businessspectator.com.au/article/2015/8/6/solar-energy/power-industry-proposes-new-age-entitlement

Sorry I didn’t realise that link was subscriber-only. Here’s a link to the image itself: http://www.businessspectator.com.au/sites/default/files/network%20returns.png

Thanks Rob