In this series of articles we’re looking to explore a few different threads of analysis into the success of the Capacity Investment Scheme (CIS) thus far.

In Part 1, I attempted to track how far — or how little — each CIS-awarded project has progressed since winning a contract in the scheme. The evidence suggested that a significant portion of projects from the earlier tenders have yet to reach financial close.

In this second part, we’ll look to examine why this may be the case, and the effect of the scheme on the PPA and contract market.

Questions we have, and have heard in recent commentary, about the CIS

As I noted in Part 1, we’ve seen an increasing amount of discussion from within the industry about how the scheme is performing in practice.

That shift was evident at last week’s Queensland Clean Energy Summit (QCES), which carried a somewhat different undertone to previous CEC events. Several aspects of the scheme received more honest or more thoughtful commentary than we’ve seen in the past, and the discussions highlighted a number of recurring questions worth examining.

How attractive has the alternative to the CIS become?

Since being announced, the CIS has quickly become the de facto route to market for many new projects. The reason is simple: the alternative — the traditional PPA and contract market — has become increasingly less bankable.

This has been one of the main findings by the Nelson Review panel. The panel have frequently used the term ‘the Tenor Gap’ to highlight how there is a mismatch between:

- The (longer) duration of firm underwriting desired by generation project proponents in order to achieve FID (Final Investment Decision, a.k.a Financial Close); and

- The (shorter) duration of tenor desired by their counter-parties.

Submissions to the review highlighted how retailers and corporates remain hesitant to take on long-dated volume risk in a future environment shaped by rapid coal exits, rising intermittent renewable penetration, and ongoing price volatility. It was originally thought that, against that backdrop, the CIS should offer developers a more attractive guarantee: a government-backed floor price that stabilises revenues and should make financing more straightforward.

The design of the scheme, however, could create a circular tension. By underwriting projects through these two-way contracts for difference, the CIS effectively removes projects from the pool of capacity that might otherwise support PPAs or forward contracts. As this Griffith University paper published last year argued, this “sterilisation” effect reduces the supply of hedgeable capacity to the broader market just as coal plants — once the dominant providers of forward cover — are exiting. The paradox is that while the CIS is meant to solve the investment challenge, it may at the same time suppress the very conditions needed for a healthier PPA and contract market to re-emerge.

The uncertainty is also exacerbated by what some are calling a looming “PPA cliff” for existing VRE assets. As Jordan Mill of Atmos Renewables pointed out at last week’s QCES conference, a significant amount of wind and solar projects built circa 2015 (under the Renewable Energy Target) will see their initial PPAs expire by the 2030s. Unless there is a robust market for secondary PPAs or other hedging instruments, many of these assets could find themselves pushed into merchant exposure.

Are bidding practices in the tender rounds sustainable?

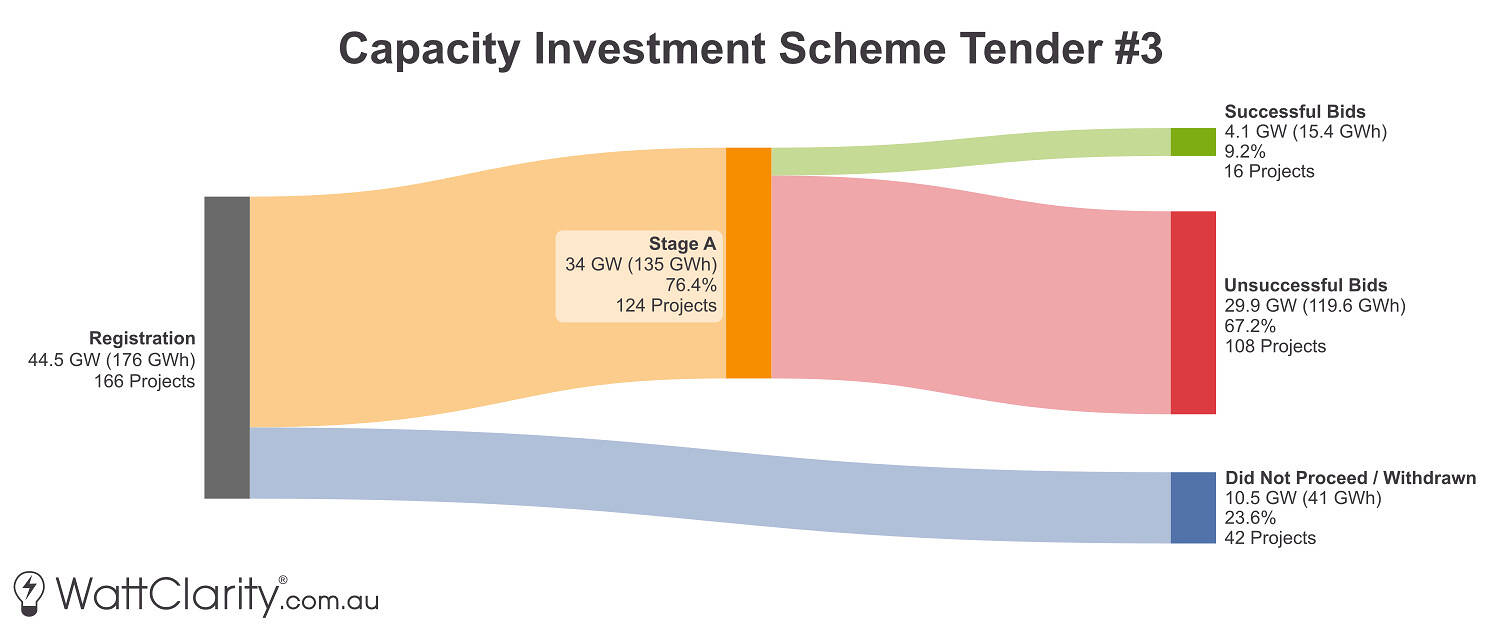

A consistent theme across each tender round has been the high level of oversubscription. Only a small fraction of registered projects – typically between 5% and 20% – have secured contracts by the end of each round.

In Tender #3 just 16 of 166 registered projects were awarded a CIS contract.

Source: DCCEEW

At last week’s QCES conference, during the ‘Project finance and offtake’ session, several speakers suggested the scheme may be incentivising applicants to bid their revenue floor at levels that are difficult to actually deliver. With the tenders heavily oversubscribed and few alternative routes to market, many believe that developers feel pressure to submit aggressive bids, often before projects are fully mature. The scale of the development pipeline reinforces this dynamic. As I noted in an article last year, the capacity of ‘proposed’ projects in the NEM has been accumulating at a rapid pace — currently sitting at 325 GW, and growing by around 26.7 GW every six months since 2022, according to AEMO’s Generation Information data.

During consultation of the scheme’s expansion, Brad Hopkins from ASL recommended that the CIS have a bond requirement (as had been the case in the LTESA scheme, and thus in Pilot Tender #1). A bond requirement however does not entirely reduce the risk that projects will bid too low. Some observers have suggested that certain applicants may, in effect, gamble their bond on the hope that their floor price can be renegotiated with the government later, instead of opting to head to the back of the long CIS queue, with few alternative routes to market.

There is also concern that EPC and BOP contracts (common construction agreements) can take up to six months to finalise after a CIS award, during which time the costs of some components and services may have risen, especially in an inflationary environment. For projects that have already bid on thin margins, such delays could push floor prices even further from economic viability.

Why have bench spots been made available?

In July it was announced that, from Tender #5 onwards, the federal government reserves a right to maintain a list of CIS ‘benchwarmers’:

“For future CIS tenders, the Australian Government may, at its direction and subject to the availability of sufficiently meritorious bids, place unsuccessful projects on a reserve list.

The reserve list will include ‘next best’ projects that the Australian Government may choose to award a CISA if the projects selected in the tender do not proceed to contract execution. Proponents will be notified if their project has been placed on the reserve list and the defined period the reserve list will remain active.”

While I’m not suggesting any definitive interpretation, this change may suggest that lessons have been learned from the lack of progress of projects selected in earlier rounds, or it may be a means for the commonwealth to maintain additional leverage over proponents who believe they can re-negotiate their floor price. On the other hand, it could just be a means for the programs administrators to justify a further expansion of the scheme’s target.

What remains unclear, however, is the size of a potential reserve list and what developers who warm the bench will be expected to do in the interim.

Key Takeaway

The CIS has quickly become the dominant route to market for prospective development projects, but the dynamics emerging around it reveal several tensions and unintended consequences on the PPA and contract market by sterilising hedgeable capacity. Some commentary suggests that oversubscription has fuelled aggressive bidding behaviour, leaving some projects financially unviable even after winning a contract. The introduction of a reserve list for future tenders adds further uncertainty about how government intends to manage project progress and market expectations.

In Part 3 and 4, we’ll look at how curtailment risk will be managed, and examine what the findings thus far from the Nelson Review may indicate about the success and legacy of the CIS.

Leave a comment