For 4 months I have been on a real-time retail electricity plan. This plan is a departure from the traditional electricity tariff structure of a day charge and a flat-rate volumetric energy charge. Instead, there is a monthly $10 subscription fee, and cost passthrough of all regulated network charges, environmental charges, and energy costs at the prevailing wholesale spot price. These spot prices can be very volatile, which has the potential to be challenging for a household like mine with low-tech appliances. To date, I have “saved” 35% relative to the Victorian Default Offer and 21% relative to my previous plan. Yet there is more to consider than just headline savings …

This post contains a brief background on electricity tariffs before jumping into my observations as a real-time pricing customer. Finally, I promote a new working paper that examines which households would pay more or less under real-time pricing. Note: This post contains my personal views only and I do not represent any firm that participates in retail electricity markets.

Background: Electricity metering, wholesale prices and retail tariffs

Historically, meters were mechanical, like an odometer. Two manual readings of the meter (usually 1-3 months apart) and you have the total usage over that period. Utilities had 2 data points available for them to use in billing – total days connected and total energy consumed. It is perhaps not surprising that most billing structures took on a similar structure: a day charge and a flat-rate volumetric energy charge.

This retail tariff structure is not ideal from an economic efficiency perspective – the cost of electrical energy can vary greatly across seasons, days, hours and sometimes minutes. Intuitively, you can think that the lowest cost power stations will run nearly all the time (or in the case of wind + solar, whenever they can), and when demand for energy is low, wholesale prices are low. But when there is a lot of electricity demand (and/or when wind + solar conditions are poor), then the higher cost power stations must start-up, pushing up wholesale prices as they need to recover their costs and earn a profit. So the tariff structure doesn’t do much to reward folks that don’t use much energy in the peak periods – instead they essentially cross-subsidise those that use energy in the peak periods. Further, the tariffs don’t incentivise the reduction of energy at peak times, privately it costs me the same to wash my clothes at midday or at 6pm, even though the true cost can be a lot more at 6pm (in terms of generating costs, and often environmental costs if factoring the cost of carbon emissions from power stations).

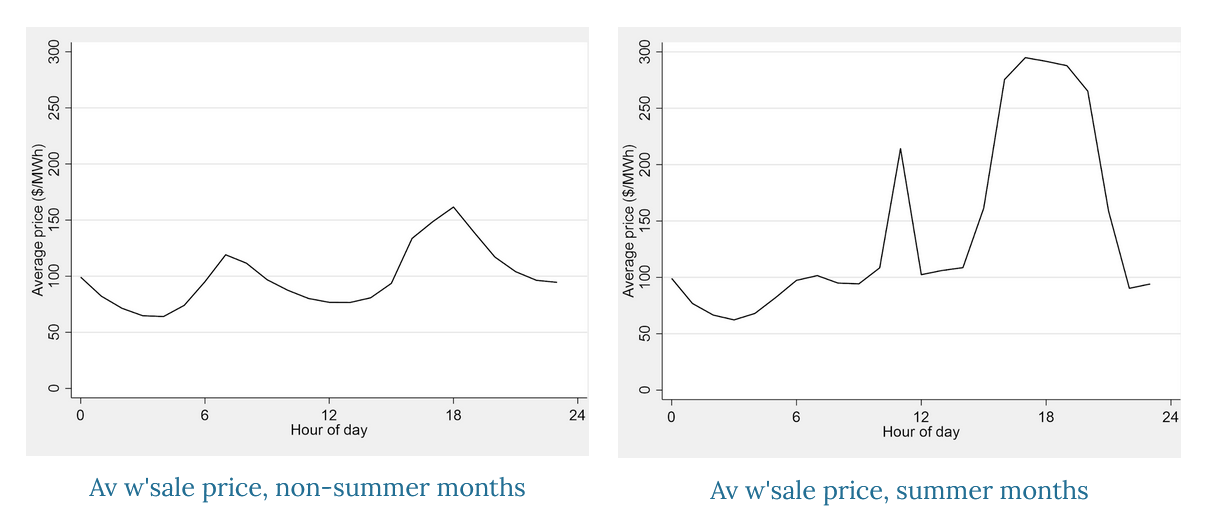

We are not talking about small wholesale price differences. Here is the average wholesale price in each hour of the day for Victoria in 2019, broken up by the non-summer and summer months. By-and-large, prices are lower overnight and during the middle-of-the-day, with a small morning peak and a larger evening peak.* In non-summer, the average trough price is about a half of the average peak price. In summer, it is about a third. This isn’t to say every evening is expensive, and every noon is cheap – it might be that a handful of days might have extremely high wholesale prices at the peak and others not so high.

Picking a retail plan in Victoria, 2018

In July 2018 I returned to Melbourne after 5+ years overseas. Upon entering a hotly contested lease for a two-storey, two-bedroom Seddon townhouse, I needed to choose my electricity retailer and plan, wondering what kind of plans I would see.

Since I’d left, Victoria had completed a complete roll-out of interval meters (known as “smart” meters) that track electrical energy use at high frequency.** I wonder if you will excuse me for thinking that the structure of tariff offerings might have changed – would retailers offer plans that would reward customers that used energy at cheaper times? It is a whole other blog post to discuss why this might not have happened, but the only viable options I could choose from consisted of a day charge and a volumetric energy charge.*** From a tariff perspective, I might as well have had a mechanical meter. I signed up to a plan that charged $0.98 a day and $0.22/kWh if I met a pay-on-time discount ($0.40/kWh if not).

This changed in 2020. A small start-up called Amber Electric entered the retail market, offering full cost passthrough for a fee of $10 a month. This plan equates to real-time pricing (RTP from here). In May I signed up to their waitlist (!! they’re really small and this is not exactly mainstream) and in August they finally signed me to their plan and I was facing RTPs.

Observations about life on real-time pricing

1) Attentiveness and the learning curve

How much does my electricity cost, and how much electrical energy does my TV use? My washing machine and dryer? My split system when heating? When cooling?

It is straightforward to see what the current RTP is via Amber’s app. But if I am sitting in my heated lounge room in winter watching Hard Quiz and I see that the price is $2.00/kWh, is it worth turning down the thermostat, or to say goodbye to Tom Gleeson and stop playing Hard?**** What if it is $0.80/kWh? What if it is $0.30/kWh?

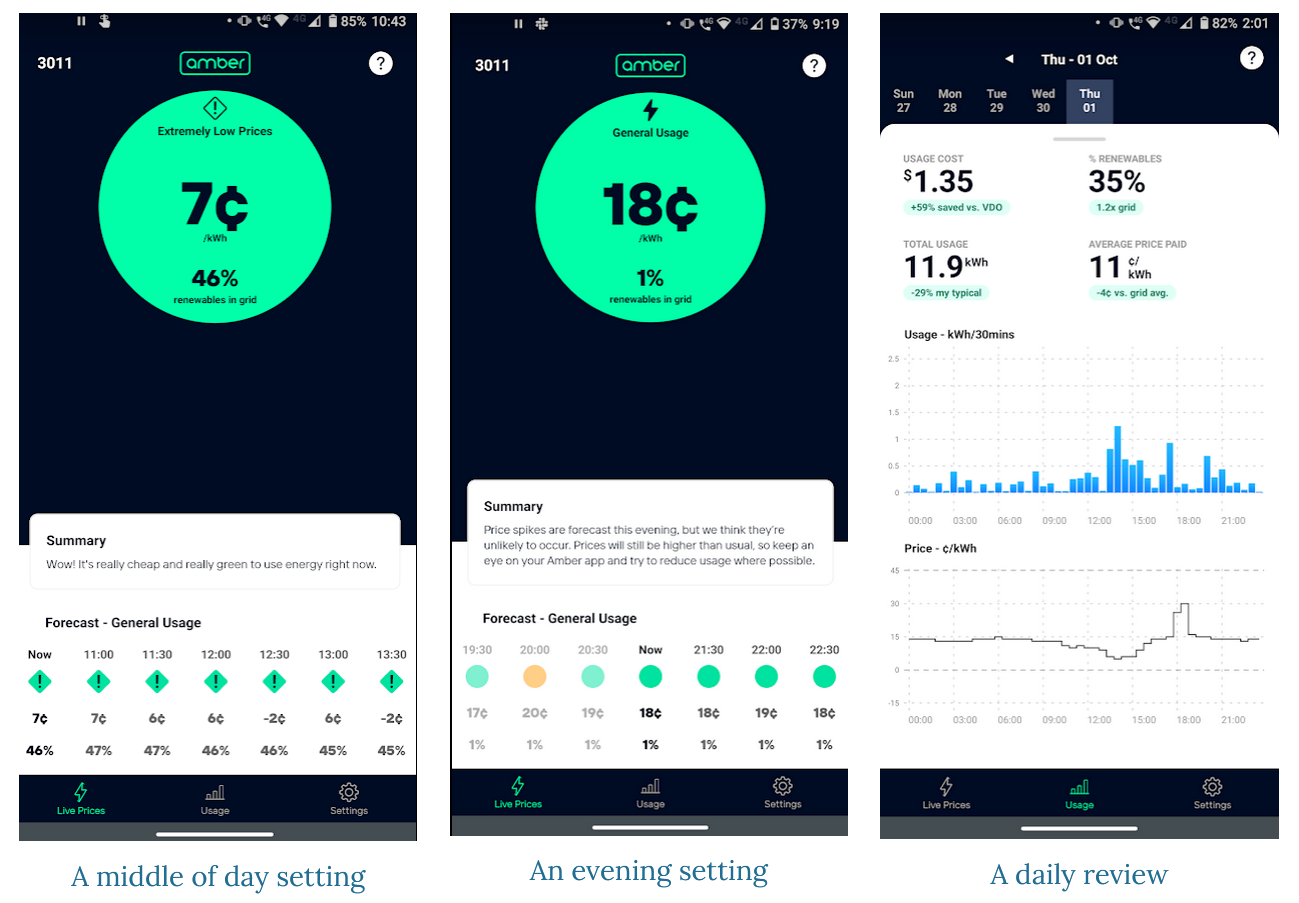

I’ll admit, novelty and a nerdish exhilaration meant that I initially checked my RTP pretty frequently and kept my eye on times of day when price forecasts were interesting (see figures below for the app representation and some prices at different times of day). I also would review my half-hourly usage the next day (see third figure below for the app representation), and pretty quickly learned that the only activity I was going to seriously adjust if prices got funky was the split system, which tends to use between 0.5-1.5kWh per half hour. Other less-intensive but somewhat flexible things such as the washer, dryer or the electric oven I’d move to what is generally a very cheap middle-of-day when I could (which was often due to us working from home during covid restrictions). The TV, lights and computers proved to be small potatoes – we didn’t really worry about them.

6 months on, I still check the price forecast most mornings, quickly review yesterday’s usage for any anomalies, and trust in the price alerts I have set up. I’ve established a few rules of thumb – e.g wash clothes between 10 and 3 – and switch non-essentials off or down if I get a >$0.50c/kWh notification. But by chance we’ve signed up during a very placid year for Victorian wholesale prices, every day it seems we face $0.11-$0.15c/kWh prices, and up to $0.18-$0.20c/kWh in the evening. Outside of my first month or two on RTP, not once have we cracked the $0.50c/kWh threshold. Overall, mostly uneventful – good for my household, I guess!

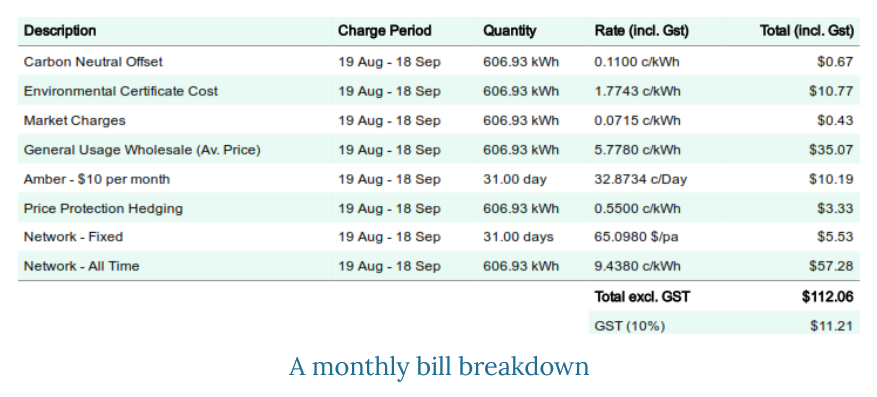

2) Network charges are dominant

Below is the bill from my most expensive month in terms of average wholesale price paid for my energy. Wholesale costs were 28% of the bill, network costs were 51% of the bill, environmental costs 9%*****, retailer costs and margin 8% and hedging costs (discussed later) 3%.

Network costs (colloquially the “poles and wires” costs) are more than half of every bill. What raises eyebrows of energy economists and commentators is that 90% of these charges (for me) come from a volumetric component – the 9.4380c/kWh rate. This is where “net metering” of rooftop solar delivers a big benefit to installers – each kWh produced by rooftop solar does not just reduce the wholesale energy costs for servicing a household, but they also avoid paying some network charges. The so-called utility death spiral is the idea that as more households install rooftop solar, network charges will have to increase for network companies to recover their costs, placing more burden on non-solar-adopters, who in turn are more incentivized to install solar. A topic for another blog post one day (or to avoid duplication, refer to this post by Severin Borenstein and many of his papers).

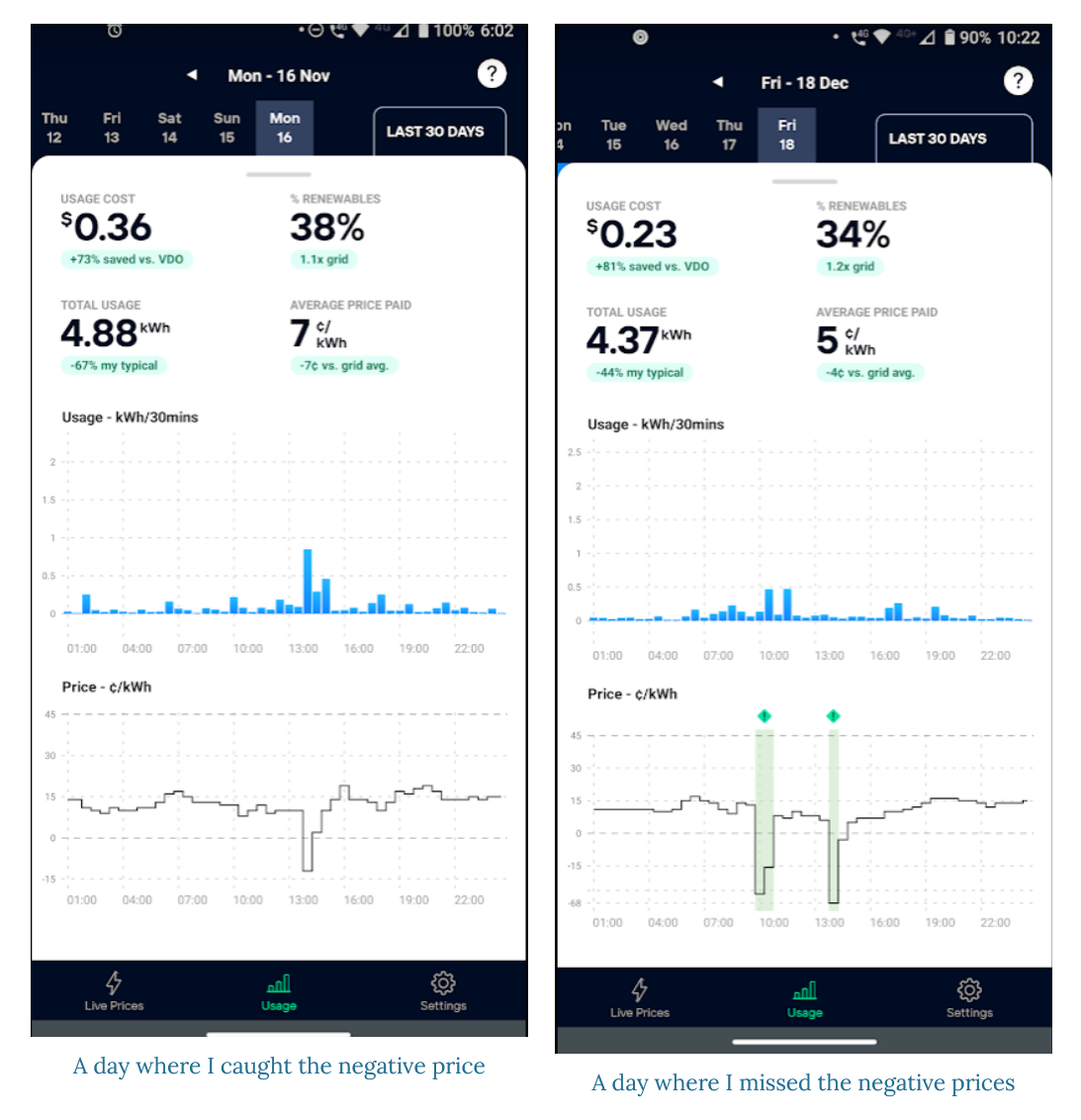

3) Negative price excitement… and disappointments

The volumetric network charge (plus some much smaller environmental and hedging charges) has another consequence when it comes to negative wholesale prices – I often can’t cash in! Wholesale negative doesn’t mean retail negative — even if energy prices are -$100/MWh, I will still pay a net positive price for electricity. So dreams of filling my bank account by running the oven and the A/C at the same time during the frequent daytime negative wholesale prices in Spring (when the sun is shining brightly and demand for energy is tepid) remain as just dreams!

Further, there were many mornings I’d wake up to see retail negative price forecasts that never eventuated – there really is a lot of uncertainty in wholesale price forecasts. One day, it actually happened. We ran a load of washing and did a lot of cooling in that half hour… and then I had to pay positive prices the next hour to finish laundry cycle (see first figure below)!

I also woke one day to see that the previous day I’d missed my chance when we were out for the afternoon (see second figure below). I guess I’ll have to chip away at my day job a bit longer, not a whole lot of coin in the household negative electricity price game!

4) Smart and dumb appliances

I live in a rental. I’m not super excited about controlling the lights and climate in my house from my smart phone, and doing so is not realistic given I don’t own the split system. However, for the first time in my life I have occasionally used the timer features to delay the start or to turn off the split system. I also use the time delay feature on the washing machine and dishwasher.

My personal preference regarding “smart” appliances that automatically manage electricity use when taking into account my preferences and spot prices: I’d only consider it for temperature management. It is the biggest driver of electricity use in our leaky townhouse and we use it a lot (so there is some money at stake), plus it is pretty easy to think about what you want (give some temperature ranges, crank it at negative prices, turn things off overnight unless it is stinking hot).

I’m open to considering more automation as life and technology changes, but I just don’t feel the need to automate much more in my household at this point in my life. An obvious exception will be if we get an electric vehicle one day, then I’m definitely going to be having fun with its charging algorithm!

5) Hedging / insurance

I paid $0.22c/kWh under my previous plan, with certainty. Off-the-bat I know I’m going to need to pay less than that on average to feel like the RTP switch is justified since I am now taking on a lot more price risk.

In Australia, this is serious stuff, and would be for many households. In the wholesale market (the National Electricity Market, or NEM), prices can get as low as -$1000/MWh (-$1.00/kWh) and as high as $14,700/MWh ($14.70/kWh). This price ceiling is extremely high relative to the rest of the world.****** Carelessly leaving my A/C on the once in a blue-moon day when the wholesale market is extremely stressed and prices hit the ceiling might cost me $0.88 in an hour under my old plan and $58.80 under real-time pricing. Worse still, if there is a persistent and expensive summer on wholesale markets, I might be on the hook for prices much greater than what I’d face under my previous $0.22/kWh plan — there are periods where I just have to use energy (A/C on a 40 degree day to keep the greyhound and the kids cool and out of the sun).

I have a strong academic interest in real-time pricing and want to experience it first hand. But I must admit that the prospect of getting smashed by wholesale prices and politely asking my wife to lay off the heater or the A/C really had me on the fence. In the end, a really crucial plan design made it easy for me to sign up: The plan offered by Amber has a $0.0055/kWh charge for hedging, whereby they insure customers at the regulated retail default offer. That is, if over 12 months my total expenditure exceeds what I would have paid under the default offer, they’ll cap my expenditure at the default offer cost. In 2020, this “Victorian Default Offer” was $1.0431 a day and $0.2787 per kWh – so a bit more pricey than my previous plan but adequate insurance all the same. Knowing what I know about the NEM, I would not have signed up for RTP without some form of hedging. This hedge might be the easiest for a retailer to communicate (“you won’t pay more than the VDO”) but to get a little wonkish, it isn’t ideal from an economic efficiency point of view. If you know you’ll blow past the VDO on an expensive year, then you will act like a flat rate customer and not respond to wholesale prices.

6) I’ve “saved” a lot of money (to date)

In the 4 bills I have received to date (3 months Spring, 1 month Summer) we have used 1604 kWh and paid $373.52. This is 35% less ($198 less) than what I would have paid under the Victorian default offer, and 21% less ($97 less) than what I would have paid under my old plan. Given that this has been a mild Summer, and wholesale prices have continued to remain much lower than usual for this time of year, I expect these savings won’t be clawed back over the remainder of the year.

These savings are meaningful but aren’t completely free. As mentioned earlier, we have taken on wholesale price risk – we’re comfortable with the risk, but there is always the chance we could end up paying more if wholesale prices increase — we might only ever be one major transmission or generator event away from having prolonged high-price periods. We also pay more attention to daily electricity costs, so it is another thing on my mind. Further, our behaviour has changed to a small degree – perhaps my family would prefer that we never factored wholesale electricity prices into our use of the thermostat or appliances? Perhaps they would have preferred I talked less about electricity and more about Mighty Max King and the Saints?

7) Final observation for the National Electricity Market (NEM) wonks – 5 minute settlement

Boy oh boy, aligning settlement prices with dispatch prices is important for RTP customers. The NEM calculates dispatch prices every 5 minutes, but the ultimate price participants pay or get paid is a 30 minute price that is the average of the 6 five minute intervals. It can be nuts. It is not unusual to have 5-minute price series that look like $1100/MWh, $20, $20, $20, $20, $20, which results in a $200/MWh settlement for the half-hour. So I might get a price alert, turn my appliances off like crazy, and then crisis averted, the wholesale component of my charge eventually lands at $0.20/kWh. Thankfully I haven’t had a series like $20, $20, $20, $20, $20 (where I have consumed some energy for 25 minutes) and then $14,700 (where the 30 minute settlement price would be $2.50/kWh, applied to all my consumption in the 30 minute interval). It does seem pretty rotten that you can consume something and have the price set after the fact. But this will soon be a footnote in NEM history, with the implementation of a rule change to align dispatch and settlement at the 5 minute level scheduled for Q4 2021.

Closing thoughts

So there you go, a dive into residential billing under real-time pricing in Victoria. For what it is worth, we’re happy and will stick with it, and we are very aware that the savings might be temporary. But it really hasn’t felt like a big deal so far. The hedging is not necessarily how I’d have drawn it up, but it did help me sign up and sleep at night. Wearing my academic economist hat, it has been a great experience to date and is helping to keep me up to speed with market outcomes and some market design and forecasting quirks in the NEM.

Finally, a quick plug for a related working paper I have just released. We take a first pass at trying to understand which households consume energy at high- and low- wholesale price times, which could inform who would benefit from real-time pricing in Victoria. Link and abstract below.

Cheers!

Identifying consumption profiles and implicit cross-subsidies under fixed-rate electricity tariffs

w/ Armin Pourkhanali and Guillaume Roger

Abstract: Wholesale electricity prices can rapidly change in real-time, yet households usually face fixed-price electricity tariffs. Therefore, households that predominantly use energy when wholesale prices are low implicitly cross-subsidize households whose energy use is more weighted to high-price periods. We develop a decomposition method that maps substation data on electricity use to demographic data, identifying the household characteristics associated with this cross-subsidization in Victoria, Australia. We find that households in areas with low house prices and high levels of renters and elderly residents are the net funders of this implicit subsidy. These households currently have the lowest average energy cost for retailers to service, and may be the greatest immediate beneficiaries if real-time retail tariffs are made available to them. Finally, we present evidence that cross-subsidy magnitudes have been growing in recent years, coincident with rapid solar generator penetration.

*: When ignoring the 11am spike in Summer, likely driven by hitting the $14,700/MWh price ceiling at some point in Summer at 11am.

**: “All” households is a little strong. 93% installed by December 2013, 99% by June 2014. https://www.audit.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/20150916-Smart-Meters.pdf

***: There were a handful of plans that had time-of-use pricing. These had one price for electricity used in “peak” hours of day (eg 7am-8pm) and another rate for off-peak. However, these plans were not very competitive when compared with the flat-rate plans, with the peak price often being much greater than the flat-rate and the off-peak only being marginally lower.

****: A plug for a paper of mine where we educate residential customers in Puebla, Mexico about the private costs of variously electricity-using actions. Increasing the Energy Cognizance of Electricity Consumers in Mexico: Results From a Field Experiment. Published in JEEM, ungated working paper link here: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3220111

*****: My understanding is that the environmental costs are the costs of Renewable Energy Certificates that are the mechanism behind achieving Renewable Energy Targets.

******: A high price ceiling is not inherently “bad” – for further information refer to the well-trodden discussion on what is known as “resource adequacy” mechanisms in wholesale markets.

This article was originally published here. Reproduced on WattClarity with permission.

————————————–

About our Guest Author

|

Gordon Leslie is an economist at Monash University, with fields of study in industrial organisation and energy economics. Gordon received his PhD at Stanford University and his BCom(Hons) and BSc from the University of Melbourne. Gordon holds affiliations with Monash’s Australian Electricity Market Initiative, and Stanford’s Program on Energy and Sustainable Development.

You can find Gordon on LinkedIn here. |

thanks for that Gordon. I am also an Amber customer (I wonder what %age of their customers are energy wonks…?) primarily for interest rather than expecting massive savings, as i know i don’t have a lot of load-shifting tools available to me at the moment. I got on the Amber train a little earlier than you about March and have since congratulated myself on my impeccable timing, as that’s pretty much when the wholesale price started to soften with slightly lower demand and falling gas prices. So you and i have front run the wholesale price falls that most other small customers will only see flow through with the change in VDO from 1 Jan (I believe). My energy wonkiness extends to keeping track of my bills for the last ten years. Thanks to Amber’s model and the lack of price shocks in Victoria since I joined I am paying pretty much the same in nominal terms for both the daily charge and the per KWh rate as when we moved into our home in 2010! see here for more detail: https://boardroomenergy.com.au/2021/01/08/the-mystery-of-the-missing-bill-shock/

Thanks Kieran, nice post. You really nailed the timing. With no exit fees (or Amber wait-lists), in usual years with a more challenging summer I guess the least cost retail customer strategy (in terms of dollars, not hassle) would be to go on to fixed-rate for summer and real-time for March-November…

Gordon, that’s what i thought too and wondered about switching out in december. Glad i didn’t as my January bill had the lowest average wholesale price so far – 2.47c/KWh! my total wholesale costs were less than $5. Of course, i agree that we can’t rely on such benign prices every January!

Gordon, the environmental certificate cost would include (or be entirely made up of, not sure) the Victorian Energy Efficiency Certificate cost, which is borne by the retailer and passed through to customers.

Thanks Kat, I had forgotten about the state-based programs when I wrote that footnote up. I’m also not across the cost-impacts of the scheme relative to the RECs.

Nice article and well articulated thoughts Gordon. I’m also a recent Amber convert (and work with C&I spot pass through). I love the Amber model, but I’ve got a couple of musings around their long term prospects in such a vertically-integrated heavy market (we have a big 3, better than Coles/Woolies or QANTAS/Virgin[/Rex?] right!)

1. Like Kieran I can’t help but feel Amber’s customer base is mostly energy nerds dogfooding our own products or at least indulging our interests. I was somewhat surprised when a non-energy industry friend of mine recently independently raised Amber over a beer saying that he was on the waitlist and keen to start with them. That being said PowerPal has been seeing great engagement from the Victorian community at large, so there’s definitely some appetite for more novel approaches to managing residential consumption and costs.

2. The back end hedging required to meet both the solar minimum FiT and VDO (at least here in Victoria) must have some significant challenges in keeping the fixed costs low.

3. I’ve joked with others that Energy Locals model of outsourcing their retail licence might be the smartest play in the retail sector, but it imposes some significant risks to the fixed costs – already Amber has had to bump the monthly charge to $15, presumably due to points #2 and #3.

4. The ESB seem intent on legislating in favour of the vertically-integrated incumbents (staring you right in the face RRO). Some of these changes could be seriously damaging to the competitiveness of small, spot-exposed and non-generation owning retailers.

just a coda on this topic following unfortunate events in Texas last week. you may have read about people there on wholesale pass through contracts who are facing bills for $1,000s because the price there (for those lucky enough to have power…) hit the cap of US$9,000/MWh and stayed there for days. Amber customers here in the NEM are not so exposed because the NEM has a rule called the Cumulative Price Threshold (CPT). This is currently $224,600/MWh. If cumulative prices over an extended period (seven days) reach this level, then AEMO effectively overrides the spot market and applies administrative pricing of $300/MWh instead. So while this situation would still be quite a bill shock for Amber customers, sustained exposure of the level seen in texas last week wouldn’t happen in the NEM. PLus if you’re in Victoria, Amber have to cap your total bill over the course of a year at the level of the VDO, so that’s a further protection.

Why do people insist on using the $0.00c format. It’s confusing. Are we talking dollars or cents here. It’s either $0.00 or 0.00c but it can’t be both $0.00c.

It’s not that hard to write one or the other format. Plus it takes up extra characters.