GSES recently gave a presentation at the APVI workshop in Brisbane as part of the International Battery Association conference. The presentation considered the drivers of battery storage, possible future business models, and the impacts on generators.

This article was collectively authored by Jono Pye (who gave the presentation at APVI) and others in the GSES team.

There is no such thing as a ‘natural market’ when it comes to electricity – there is nothing natural about buying and selling electrons.

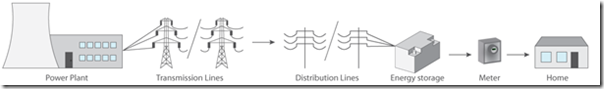

All electricity markets are designed around the technology available at the time, which up until now has been large centralised generators that are located close to their fossil fuel resource. The business models of generators, transmission/distribution companies and retailers are similarly based on the available technology (and existing market).

Distributed PV has already had a serious impact on presumed business models. It is constantly flagged that soon the price of batteries will fall to the point where distributed storage is common place. Such a dramatic shift in the technology of the electricity market promises to disrupt many of the incumbent players . Much has been written about the utility ‘death spiral’, in which utilities, facing a reduction in the use of their networks, will increase the unit cost of energy to make up their revenue, which in turn will increase the incentive for customers to use less energy.

Batteries have the potential to provide the death stroke to utilities by potentially supplying all of a customer’s energy needs. However this assumes two things:

1) that customers are willing to provide their own capital for the investment, and

2) that there is either no need for a back-up power source or that a grid connection is more expensive than a generator.

In suburban areas with houses powered by distributed PV with battery storage, there will still be the need for a grid and a utility to manage it. The question then becomes: how will distributed storage integrate into the current market?

To a large extent this will depend on which stakeholders in the industry retain ownership of the batteries; whether this ownership rests with private individuals, utilities or a new type of gentailer.

Private Ownership

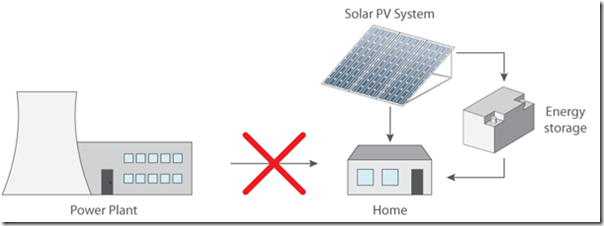

Privately owned systems present the greatest threat to utilities and retailers, as customers with these systems are theoretically able to provide all their own energy needs.

Although there will be a market for these systems, they will have a high upfront cost and leave the owner responsible for their maintenance and to pay for equipment failures in the system.

The group of customers that go down this path of self-ownership will be the early adopters; those that have been waiting eagerly for the price of batteries to drop to a point they can exploit their PV systems to their full potential, and be completely self-reliant.

Distributed storage will allow customers to leave the grid entirely.

Utility Ownership

The role of a utility is to provide the infrastructure required for consumers to have access to electricity – batteries could be viewed as a simple extension of this infrastructure.

Utilities could provide batteries at street level that were owned and operated by the utility, dispatching during peak times to reduce the demand and strain on their network.

How this would function with the wholesale electricity market (and the market rules) would be challenging, with the utilities themselves buying electricity during low periods to charge batteries, and using it to suppress demand during peaks.

Utilities could operate batteries either at a street or residential level.

Utilities could also provide batteries in the home. In this situation, the utility would retain ownership of the battery and lease its use to the customer. Customers could then choose how they utilise the system; either storing energy from their PV array, or from the grid during low demand.

Whatever the ownership model, in this new market there will still be a need for a back-up power source: to provide power for PV customers during periods of low irradiance, and to charge the batteries of those customers who do not have PV.

Gentailer Ownership

The purpose of an energy retailer is to buy energy from the wholesale market on a customer’s behalf and deliver it to their door, paying the network providers for their services along the way.

In order to ensure they can supply the required energy throughout the day, retailers either hold Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs), or physically hedge themselves with their own fleet of generators. Coal traditionally supplies the baseline, with open and combined cycle gas turbines supplying the peaks.

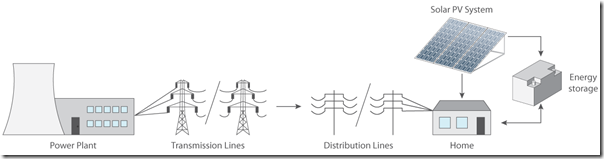

In many ways, distributed storage can be thought of in the same way as a peaking generator. When a retailer acquires a new customer, instead of ensuring they have enough generation or futures contracts to cover the new demand, they will also have the option to install a storage system (either with or without PV).

Gentailers could install and operate battery systems to reduce a customers’ supply cost

Retailers will be able to provide customers with the energy they need through a mixture of battery storage, PV, and the wholesale market. This mixture can be optimised to suit either their generation assets or existing power purchase agreements.

The benefit to customers in this situation is that all risk and responsibility are carried by the retailer. Very little changes in the way the consumer must think of their energy consumption: being able to pay either a fixed monthly lease payment, or a tariff rate for their energy.

This model also provides Gentailers with an incentive to maintain the system and process equipment at its end of life, hopefully leading to responsible recycling and reclamation of these products.

About our Guest Author

This article was collectively authored by Jono Pye, and others in the team at GSES (Global Sustainable Energy Solutions).

GSES is a renewable energy engineering, training and consultancy company specialising in photovoltaic solar design, online and face-to-face solar training, publishing solar books and PV system audits.

Further background to Jono can be found on Jono’s LinkedIn profile.

I think you are missing the other option that will be relevant in many locations. Community ownership can be considered a mix of private and utility ownership where the term “distributed” really comes into its own – and local smart-grids can implement the integration of all relevant options in the most economical way.

Local smart-grids (community or utility owned) will need to operate like the internet, where various levels of operation will occur to meet current conditions. As far as end-users are concerned, their power supplies should be seamlessly selected from the available supplies – via the transmission system or from local sources depending on availability, security and cost considerations.

Hi Ian

Thanks for adding that one.

There could be others evolve, as well – in the NEM there are a couple of Demand Response Aggregators operating in a variety of forms. It may be them that take the step of owning and dispatching the resources.

Paul

Hi Ian,

I think you raise a good point, local mini grids have many advantages and I think there is definite potential for these, particularly in rural areas. The business model will be much more of a complete energy provider, supplying both generation and distribution (gentility?). There is the potential for a large cost saving with this model, and I think it will become more common as the price of storage drops below distribution infrastructure costs.

Jono.

Hi

just had to say that a co-op and that is what you are getting at will not work (sorry) no co-op works that good.

Stand alone is the only way to go. Generate your own power,store it in battery’s and use it when you need it.

Now generating power and have it on hand is the hard part so it seems I must admit that it could not be done however I have seen a genorator that works off a 12 volt system and genorates it’s own power running an inverter that runs this persons home. He made it in his shed.

It was something I had never seen before and I have been round for 1/2 a century. It really did work how I do not know! Will he make another one not sure! Will he sell it I can give the answer to that NO I tried to buy it but no way and I had to make sure I did not tell anyone his name or where he lives.

Thanks

David.

No co-op works that well?

http://reic.uwcc.wisc.edu/electric/

http://www.mondragon-corporation.com/eng/co-operative-experience/history/

“No co-op works that good” – Have you heard of Fonterra? It is the largest company in New Zealand and one of the largest dairy companies in the world which is a cooperative owned by dairy farmers. WIth $18B in annual revenue and $700M in profit I would say Fonterra “works good”

I would have thought coops for electrons would suffer seriously with small scale operation due to the problem of peak demand and all electrons not being of the same value at varying times. The coop would clearly need to engage itself with demand management- ie smart meters and peak pricing and the investment and admin of that on a small scale may well prove the greatest hurdle, absent the economies of scale of Big Gen now.

As well we live in a mobile world and attaching a lien to my home via a street, block or whole suburb power coop would be one I’d have to carefully consider buying into. After all if I sell up and move, there’s no guarantee the next buyer wants to be shackled with my home’s power coop obligation. That would leave most to consider stand alone system economics only and their risk return should there be a change of plans and any forced move in future. Again Big Gen has the edge over any small scale coop there.