My sincere apologies if you’ve clicked on this article expecting a concise answer to the question(s) in its title… Instead, it’s something that I want to pose to our readers.

Background

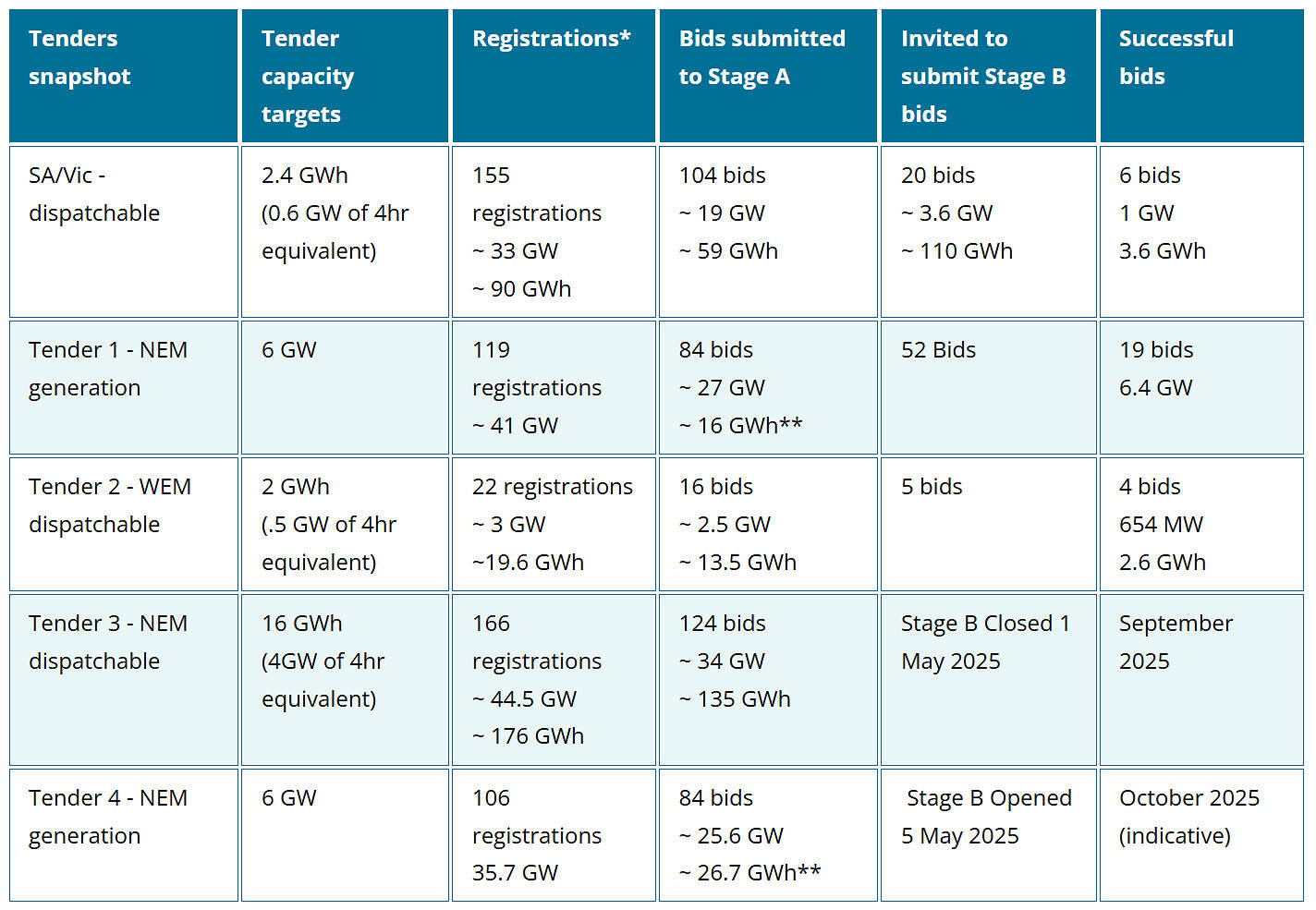

As a quick refresher, the Capacity Investment Scheme (CIS) was announced in December 2022 by Albanese government, and was at least partly designed to be an alternative to former proposals to introduce a formal capacity market into the NEM. The CIS aims to incentivise 23 GW of new generation (such as wind and solar farms) and 9 GW of storage (such as batteries) to enter the market by 2030.

In simple terms the scheme does this by providing revenue collars that underwrite downside risk (but also split revenue upside) for projects that win a contract in the scheme. Tender #1 and #2 of the scheme have already been completed, with Tender #3 and #4 currently in progress.

Tender #1 and Tender #4 of the CIS are open to generation projects (e.g. solar and wind projects) in the NEM. Tender #2 and #3 are open to ‘clean dispatchable’ projects (e.g. utility-scale batteries) in the WEM and NEM, respectively. Hybrid projects are allowed to bid for either type of tender.

For more details, you can find our analysis and ongoing commentary on the CIS here.

Merit Criterion 1? Volume Risk? Force Majeure?

On Tuesday I was forwarded this article by Ben Beattie, which argues that the CIS — in his view — shifts more risk and cost onto taxpayers than initially anticipated. Specifically, he focuses on who bears the brunt of curtailment risk for projects.

As our team is very much focused on the day-to-day machinations of the NEM, I have not been following the CIS tendering process closely, but I have been curious as to how the scheme interacts with congestion risks that are likely to eventuate for some of these projects.

Merit Criterion 1 of the scheme — noted on page 4 of the latest briefing note — makes it clear that the scheme administrators are seeking:

Projects intending to locate:

- in strong areas of the network, or

- with a connection that is not likely to lead to material curtailment and/or Congestion of the Project’s own generation or the generation of nearby renewable projects.

However, forecasting congestion and curtailment is difficult, especially over a multi-year time horizon. Therefore, I’ve been interested to understand how this risk interacts with the scheme’s revenue floor mechanism.

Some of the earlier commentary, interpreted the scheme’s design to incorporate shared volume risk (along with some level of price risk), such as this piece by David Feeney from the Australian Energy Council, which states:

If a project underperforms – e.g. if it is curtailed more often, or the weather resource turns out to be lower than expected, then the project is more likely to fall below the revenue floor and the government will have to pay out more than it expected to. In this way, volume risk is shared with the government to a greater degree than other support schemes. Price risk is also shared, although this can be partially mitigated by a zero-price floor clause where negative prices do not contribute towards the annual revenue calculation. The risks of poor forecasting are lower the more the government can rely on independent input assumptions about each project’s expected performance.

However, when the implementation design paper was released in March last year, the federal government clarified that volume risk would not be covered. Page 18 of that document states:

Net revenues are divided by the generation (adjusted for Marginal Loss Factors and Distribution Loss Factors) sent out by the project in that quarter (in MWh). This incentivises the project to maximise the generation it produces and places any volume risk with the Project Operator who is best placed to manage that risk.

Now back to Ben’s article…

In it he walks through how the quarterly top-up payments are calculated, and claims that CIS projects are financially well protected from curtailment or congestion. That statement piqued my interest, so I started digging to verify (or refute) this claim.

Ben refers to the terms of the CISA (Capacity Investment Scheme Agreement) pro-forma for Tender #1.

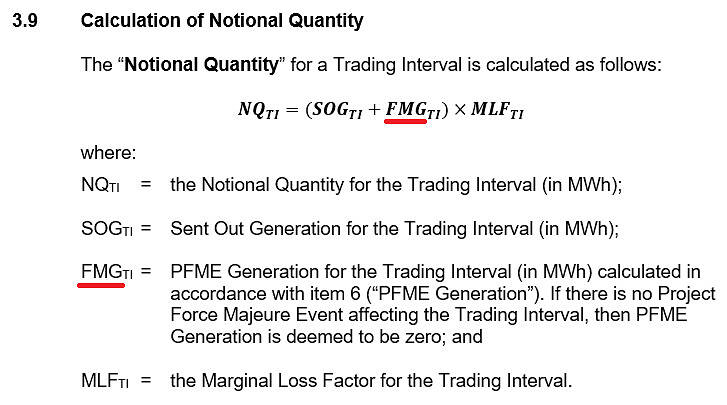

In reviewing his claims I’ve noticed that the calculation methodology appears to have changed for Tender #4. In particular, I’ve spotted that “Force Majeure Generation” seems to have been removed entirely in the calculation of the revenue floor in the latest documentation.

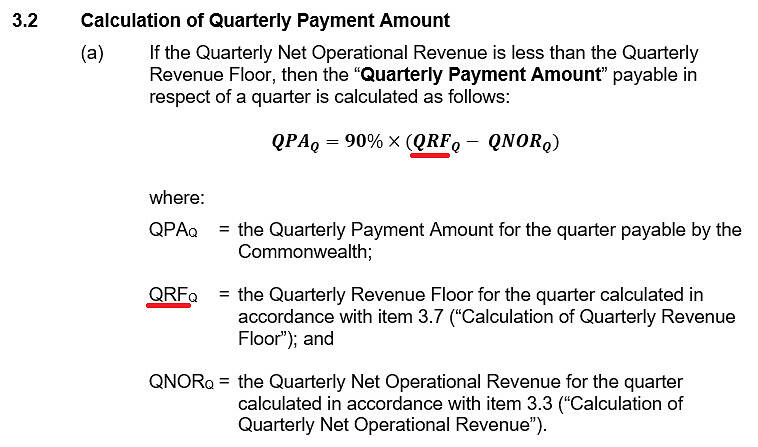

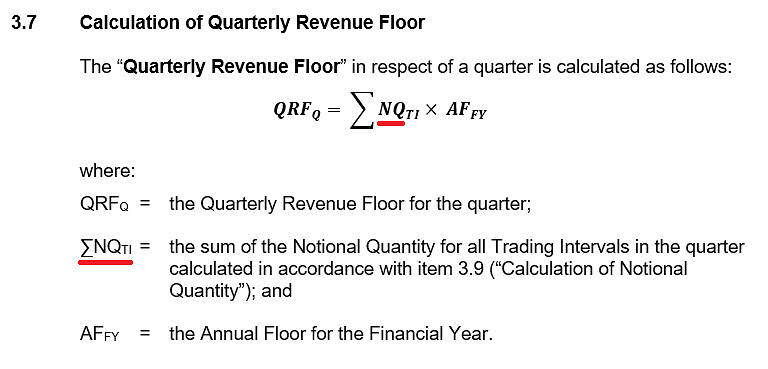

Below I’ve highlighted the relevant terms in the underlying calculations for the quarterly revenue floor payments (as Ben did in his article), but have presented a comparison between the two documents:

| Section | CISA Terms for Tender #1 | CISA Terms for Tender #4 |

|---|---|---|

| Schedule 1, Section 3.2 (a)

Calculation of Quarterly Payment Amount in regard to Revenue Floor |

|

|

| Schedule 1, Section 3.7

Calculation of Quarterly Revenue Floor |

|

|

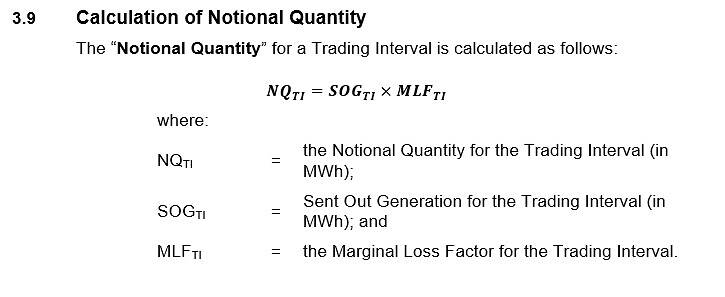

| Schedule 1, Section 3.9

Calculation of Notional Quantity |

|

|

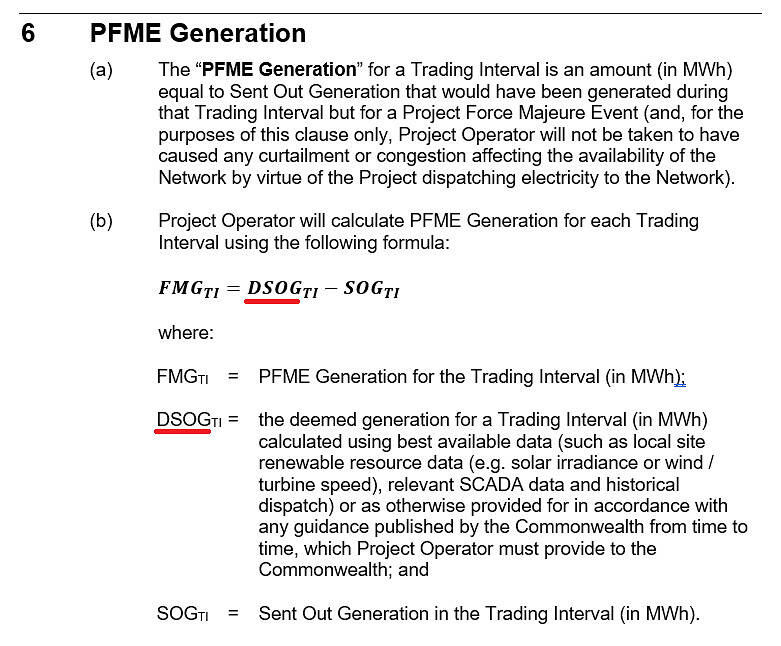

| Schedule 1, Section 6

Force Majeure Generation |

|

Removed |

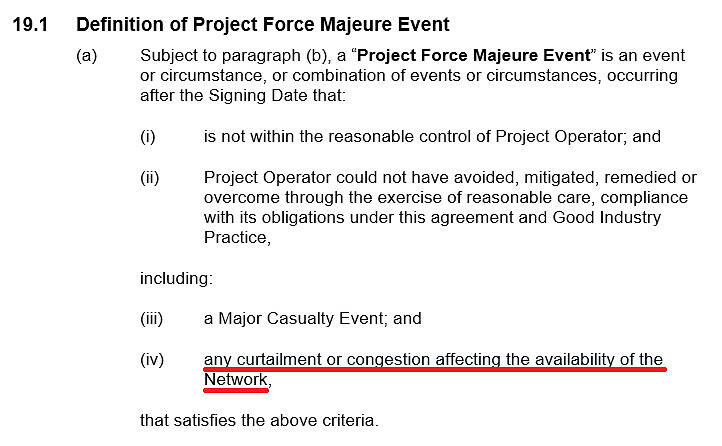

| Section 19.1 (a)

Project Force Majeure Events |

|

|

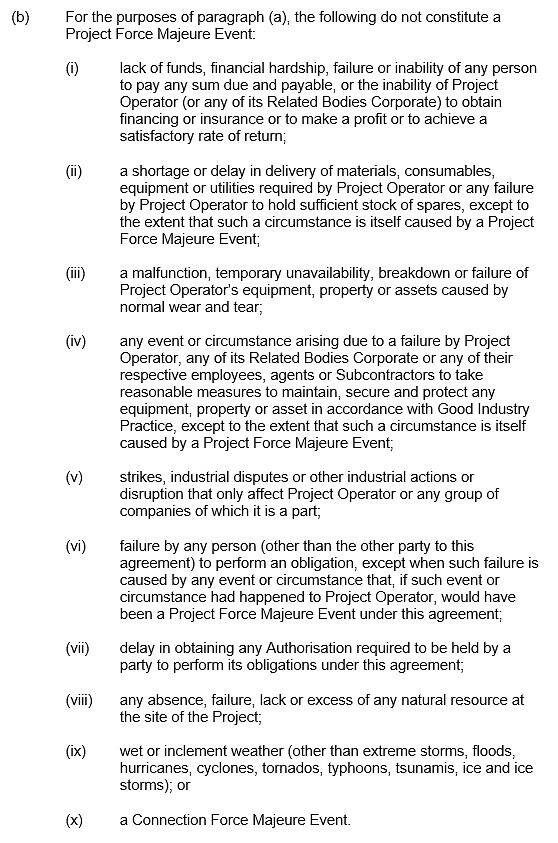

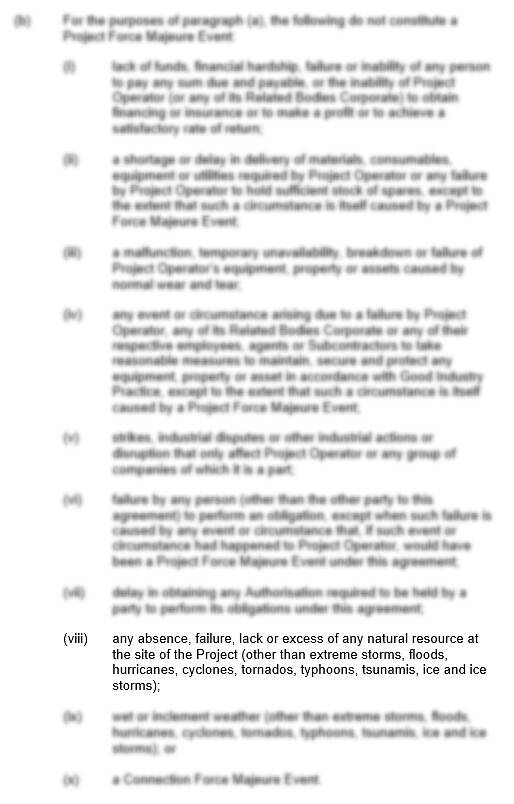

| Section 19.1 (b)

Project Force Majeure Event Exclusions |

|

|

While the clause explicitly states that ‘Force Majeure Generation’ includes “any curtailment or congestion affecting the availability of the network”, the sequence of wording used in that statement is somewhat ambiguous. The accompanying list of exclusions further complicates how one would interpret what is covered.

It’s also worth noting that both documents also specify different calculations for hybrid and staged projects, but I won’t delve into that here.

Ben’s claims are centered around the argument that the revenue floor factors in generation and curtailment — and he argues that curtailment will make the floor higher, and therefore provide a bigger cushion, funded by the government. However, the calculation for the quarterly revenue floor (Schedule 1, Section 3.7) is also dependent on the ‘annual floor’ price, so it is not guaranteed that the quarterly revenue floor will be unreasonably high relative to the operational revenue. The annual floor price forms part of the tender bid, so that it supports a competitive tender. Therefore one might presume that it would be set so that it results in a competitive quarterly revenue floor.

To be clear, I’m not offering a definitive interpretation or criticising any party. I’m simply trying to understand how to interpret the wording of the agreement, why the calculation has shifted between tenders, and to what extent curtailment is actually covered under each agreement.

What do you know?

The CIS is still relatively young, and much of its finer design remains lightly sketched in public commentary — so a few questions I’d like to throw open to WattClarity readers are:

- how should we interpret the CISA wording of “any curtailment or congestion affecting the availability of the network”?

- for tender #1 winners, does project curtailment constitute a project force majeure event? how does this apply differently for tender #4 winners?

- if the CIS does cover curtailment, how would this be measured practically and accurately for compliance (given all the complexities of attributing curtailment causes, such as 0 inverter constraints)?

- is it reasonable to assume that the annual floor will be at a level that produces a competitive quarterly revenue floor (for each successful bid)?

Let us know what you know — either in the comments below, via LinkedIn or Twitter/X or drop us a line. We’re particularly interested in hearing from anyone who has been more closely following the design of the scheme or tendering process.

Editor’s note:

2025-10-01 2:02PM

Thank you to all those who emailed in with their thoughts. DCCEEW have since clarified that the document I referenced above as “Tender #1” was actually a draft version of this document. They have clarified that in the final version of the document, PFME generation was excluded as a component of the notional quantity calculation.

The final updated document was published shortly before Stage B of that tender process began. I’ve written some thoughts and questions about the timing of that change, and what effect it might have had on the bidding process, in this subsequent article.

Thanks Dan, plenty to talk about, and interested to see others’ interpretation.