In the previous article on reducing electricity costs we looked at energy efficiency and the fact that the cheapest electricity is the electricity that you don’t consume.

In this article we will look at how to pay less for the electrons that you do consume.

The article is based on Chapter 13 (Step 6) of my book “Power Profits – A Comprehensive 9-Step Framework for Reducing Electricity Costs and Boosting Profits”.

Retailers bundle up electricity products into a vanilla product that have risk premiums and profit margins built into them, and many businesses are unaware that there are alternatives to buying electricity at these risk-premium-laden fixed prices.

The standard retail contract

Most businesses in Australia purchase electricity as a bundled retail product from a licensed retailer. The retailer takes care of the administration of the customer’s supply service, so that the customer need only turn on the switch and electrons start flowing, and a bill turns up each month.

The retailer is doing a lot of work in the background that the customer never sees, such as:

- Contracting for electricity to supply to the customer

- purchasing the environmental certificates required to meet the customer’s obligations

- organising a meter agent to monitor, record and report consumption data from the meter

- paying the network provider for transmission and distribution charges

- calculating the bill and sending bills to customers and ensuring that they pay.

All of this work takes human effort as well as automated processes, and therefore there are associated costs. Retailers are not in the business of providing free services; their owners – government, local shareholders or overseas companies – require the retailer to make a profit, so they charge a profit margin on the provision of the electricity supply service. All of this is fair and reasonable, as it would cost most businesses more to do this work themselves, unless they are extremely large electricity consumers.

The hidden cost

However, retailers provide another service that most businesses don’t even realise they are getting, and it’s an expensive service. Retailers provide a risk management service (insurance service) bundled in with the supply of the electricity, often at high risk premiums.

There are quite a few risks that the retailer takes away from the customer, including:

- volume risk: the risk of exposure to the wholesale market if the customer does not consume the exact amount of electricity assumed in the supply agreement

- load profile risk: the risk of exposure to the wholesale market if the customer does not use electricity throughout the day, week, month and year as was assumed in the supply agreement

- market risk: the risk of exposure to fluctuations in prices in the electricity market

- credit default risk: the risk to the retailer if the customer cannot pay their bills.

To some extent the retailer smooths out the risks by aggregating all of the different customers into one or more portfolios, thus reducing the large number of individual risks into one or more portfolio risks.

The profit risk to the retailer can then be stress tested against different scenarios, such as large movements in average market prices and changes in the overall economy that affect demand and credit defaults. The impact of the assumptions made in an individual supply contract can also be tested against the overall portfolio.

So, the poor old retailer is bearing the brunt of everybody else’s risks. As the retailer is having to wear those risks, it charges a premium to do so, and that premium reflects worst-case scenarios. Instead of the retailer being burdened by the weight of their customers’ risks, it is now feeling the weight of potential sacks of gold over its shoulders. If the worst-case scenarios do not manifest, then they get to pocket the worst-case scenario premiums that they have charged their customers.

The customers who enter into a straightforward vanilla electricity supply agreement pay the following price for the energy component of their bill:

Retail energy price = Wholesale energy price + Administration costs + Risk premium (volume, load profile and credit risks) + Retailer margin

There are other options

Many businesses don’t even realise that there are other options for purchasing electricity. Negotiating a good price on a standard retail contract might seem like a good approach, but if you understand the intricacies of the electricity market and the electricity requirements of your business, you can achieve huge financial benefits if you get a bit more creative with your electricity purchasing.

Managing your own risk

The risk premium that the retailer builds in assumes that the customer has no ability to manage its own risk. However, there are ways that the customer can manage its own risk through demand side management (DSM) to avoid high prices and achieve very low average prices compared to what is offered by the fixed retail offers.

Load curtailment

The first DSM method is load curtailment. By monitoring market half-hour prices, businesses can reduce their load when price spikes occur and avoid the very high prices that sometimes drag the average monthly price above the median price.

Load shifting

The second DSM method is load shifting. By understanding likely price patterns, such as early morning and late afternoon price increases, businesses can often shift their load – to some extent – to maximise the exposure to the very low prices and minimise their exposure to the higher prices. In recent years, middle-of-the-day prices are very low due to solar generation.

Great examples of end users who can apply this are irrigators and water utilities that can schedule pumping at times when prices are historically low, while not running when prices are historically higher. Couple that method with load curtailment to avoid the price spikes and these businesses can achieve average prices well below the fixed retail price offers.

Adopting a pool price pass-through strategy

So, your business carries out an analysis of the electricity spot market, your own load profile and operating constraints, and weighs up the opportunities and risks of adopting a pool price pass- through strategy. But where to from here?

There are two ways you can adopt a pool price pass-through strategy:

- The first is to contract with a retailer to supply you on the basis of pool pass-through prices. With this type of supply arrangement, the retailer will charge a management fee to cover their own costs and to make a margin. The cost of the management fee will be an important consideration.

- The second way is to become an electricity market participant as an end-user participant. This method is usually only viable for very large users and requires significant management oversight.

Let’s consider each of these options.

Wholesale prices through a retailer

There is an alternative to paying what can be very large risk premiums which most businesses don’t even know about. Businesses can buy electricity at wholesale prices through a retailer and keep the risk premium in their own pockets.

This leads to a new price calculation for the business, with the difference shown here:

| Strategy | Formula |

| Plain Vanilla

i.e. the traditional retail procurement approach, described above |

Price you pay, as an energy user = Wholesale energy price + Administration costs + Risk premium (volume, load profile and credit risks) + Retailer margin |

| Buying on spot

one option for doing this is to arrange for wholesale prices through a retailer |

Price you pay, as an energy user = Market pool price + Administration costs + Retailer margin |

The key difference (from the “Plain Vanilla” traditional arrangement) are:

- that the market pool price is not fixed – it fluctuates every half hour, and the average cost will vary from month to month; and

- the customer is not paying the risk premium.

Many of the large retailers are not interested in providing a pool price pass-through product to customers. Aside from the fact that they may make less margin as the risk premiums that they usually receive are no longer part of a bundled supply agreement, their billing systems are often not set up for it. It may require someone to manage a single customer with their own spreadsheet outside the normal billing system. They also may consider that the credit risk, or risk of default, is higher. They therefore usually only, begrudgingly, offer this type of facility to very large customers, and usually with a large management fee.

Small and medium-size retailers are often more flexible and willing to offer a pool price pass-through arrangement. The management fee varies considerably between retailers, and it is important to find one that provides the best service and/or price. You can go out to tender or make a request for proposals from retailers for a pool price pass-through supply offer, and then simply compare the product offerings. This will be largely, though not solely, based on price.

Some retailers are becoming innovative in this space and are offering a product that allows the customer to switch between pool price pass-through and fixed retail each month, or to take a combination of both. Some retailers provide price alerts and other information services that add value to their offer.

Going directly to the market

A large user may opt not to pay the retailer any management fee and become a market participant themselves. This is something we did in one of the businesses that I worked for.

We had already established ourselves as market participants in the gas short-term trading market, and the leap to doing something very similar for electricity was not very large.

However, inevitably there is still a substantial cost in managing the obligations that a market participant has, whether you outsource this function or employ someone and bring it in house. If the cost of becoming a market participant is not too different to the retailer management fee then I would suggest going with the retailer product instead.

In this case of doing it yourself, the electricity cost equation becomes:

Wholesale price = Market pool price + Administration costs (internal and/or 3rd party)

Wholesale Market Pool Price Pass through Strategy In Action

Our historical data analysis has shown that if you adopt a pool price pass-through strategy your average price for the full year is likely to be at or below the best fixed retail price. In South Australia it is likely to be significantly below and depending on your load profile it may well be lower in Queensland. In Victoria and NSW the average price is likely to be near the fixed retail price.

However, you can achieve even lower prices by actively managing your electricity usage and avoiding the higher price periods and the price spikes. It is the short-term duration price spikes that drive the average price up. The high price spikes can be largely avoided by adopting a load curtailment schedule.

Developing a load curtailment schedule

So how do you develop a load curtailment schedule that optimises your electricity cost without impacting your customer service and supply of products?

The Theory of Constraints

This is where we turn to the Theory of Constraints. The Theory of Constraints posits that with any manageable system – for example, a plant – there is one constraint, sometimes more, but rarely many. This means that there are usually many processes that are not constrained and can be turned off, or curtailed, without impacting the efficiency of the total supply chain.

We need to identify the critical asset or assets that are constrained and then determine the opportunity cost of shutting down the asset, if at all possible.

The opportunity cost establishes a break-even point where if that asset were to not operate for a short period of time then the opportunity cost equals the financial benefit of operating.

There are of course other considerations. The customer should see no impact from curtailing load and should be oblivious to the fact that you do curtail as part of your operations management.

Also, some types of equipment – particularly equipment that runs at high temperatures – are not designed to be shut down and restarted for short periods of time. This equipment may experience thermal shock, which will have a deleterious impact on equipment integrity or shorten its service life. For example, equipment that operates at elevated temperatures is usually refractory lined, and thermally cycling this equipment will have an impact on refractory life.

The other non-constrained assets are those that are not required to run all of the time. This equipment is often shut down because the buffer stock after its process fills up or its scheduled operating time is less than the constrained asset run time. It is this equipment that we largely target to curtail in the event of high price spikes.

I’ve had clients who initially say there’s no way they could contemplate shutting down equipment even for half an hour as it would impact upon costumer supply or service. However, when I have analysed those same plants I have found that they consistently shut down every day for morning and afternoon tea, lunch, meetings, breakdowns, and for full stock. They were often surprised at how often they actually shut down.

Other clients have asked what they should do with their labour when they do shut down. There is always opportunity for clean ups, communication meetings, training, equipment risk assessments, and the list goes on.

On the other end of the spectrum, I’ve had clients that have said they would shut everything down when price events occur at a particularly high level; for example, $1,000/MWh. This strategy may be effective if capacity exceeds demand, but it does not allow the fine tuning of cost reduction by curtailing equipment that’s not required when prices rise above a lower threshold; for example, $100/MWh.

Risk Management

But, isn’t it risky not to use standard retail contracts?

Going a different way does have risk, but risk does not mean “risky”. Risk is simply uncertainty.

With a pool price strategy, the average annual price is not certain and so there is a risk. A retail price is fixed and so there is no price risk. However, there is a very high risk that the fixed retail price will be higher than the average wholesale market price over a full year.

Tom Adams, a former executive director of Energy Probe, an industry watchdog in Canada, has a great analogy about paying for fixed retail contracts: “Over a lifetime of driving, you know you’ll replace a couple of windshields. But if you insure your windshield, you don’t pay for two windshields – you pay for 10.”

So yes, a spot exposure strategy is “riskier” than a vanilla fixed retail contract, and with taking on that “risk” there is an expectation of a return. History has shown that the worst possible outcome from a pool price exposure strategy has been close to the best retail offer prices, depending on the timing of the retail offer.

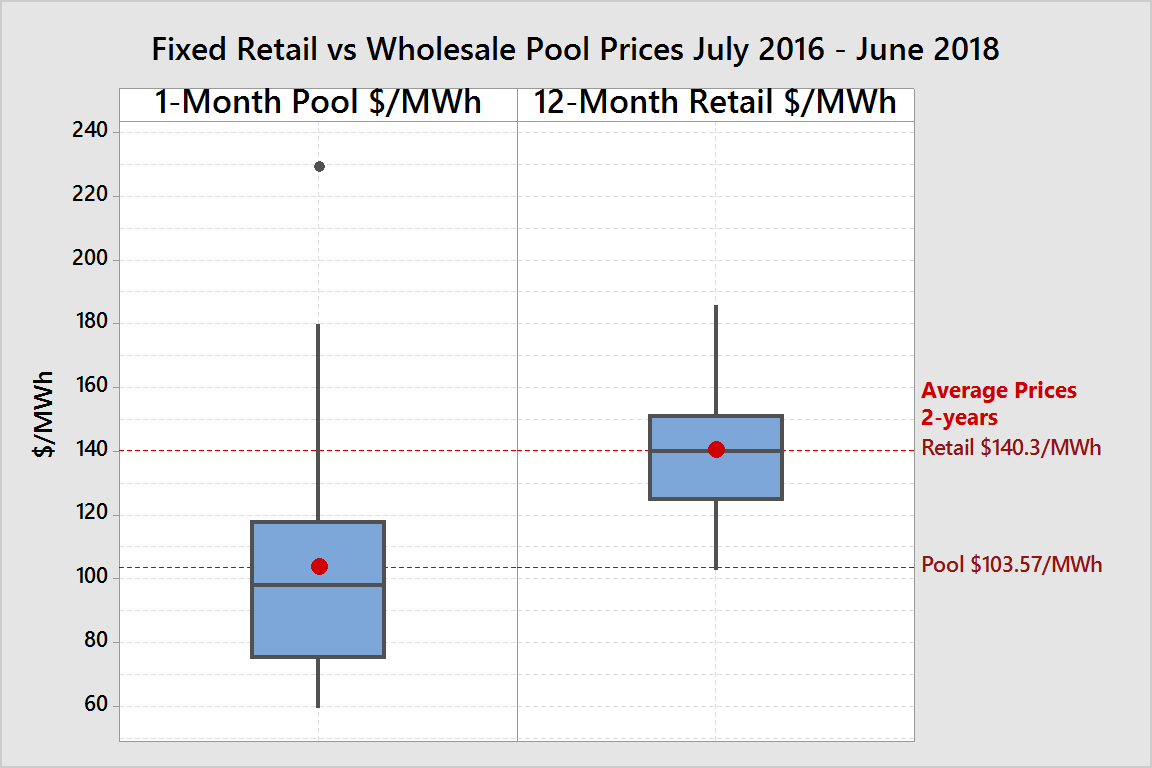

The chart below shows box plots for the average monthly prices for the South Australian wholesale market from July 2016 to June 2018 (2-years) and for typical 12-month retail price offers made each month over that same period. For an explanation of box plots see here.

It’s not quite comparing “apples with apples” as one box reflects actual monthly spot prices whereas the other box indicates fixed price offers for the next 12-months. However, the chart shows the difference in the volatility and average between wholesale and retail markets over a corresponding period. Each box pot contains 24 data points relating to monthly data over 2-years. The standard deviation (volatility) of wholesale pool pricing was 39.9 and it was 22.2 for the fixed retail pricing. So, the average wholesale monthly average pool price was almost twice as volatile (risky) than the wholesale market monthly average price.

However, when we examine the average prices for the wholesale market over the 2-year period and the average 12-month retail price offers we can see that the fixed price average offer was $140.32/MWh and the average wholesale pool price was $103.57/MWh. That is a difference of $36.75/MWh (3.7 c/kWh).

In my 17-years of experience of being 100% exposed to the wholesale market pool price in South Australia, I have found that the annual wholesale market pool price was at least the same as the best fixed retail price offer and most often significantly lower.

The box plots in the chart show that you may have got your timing right and achieved a fixed price offer at the bottom of the fixed retail box “whisker”, however, that price was only as good as the average wholesale price over the 2-year period.

The trick for businesses is to understand historical price volatility and annual average prices, overlay your informed view of what is happening in the market structure on the coming years, and then compare that with fixed price offers. If your informed view of likely market price distribution outcomes is at or above a fixed price offer, then by all means lock in the fixed price offer. If your informed view is that market prices are likely to average below the best fixed price offer, then why would you want to lock in high prices?

I think it is risky for businesses to lock in high fixed price contracts without having regard for the likely outcome of variable market price outcomes. The clever businesses realise this and embrace the so-called “risk”.

Electricity price risk management strategies

Clever businesses understand risk and so are able to develop and implement risk management strategies to either further reduce their costs or limit downside risk. Electricity price risk can be managed using many different strategies:

- a retail contract fixes the price and gives certainty, but includes a large risk premium

- a wholesale pool price exposure with load curtailment reduces exposure to high price spikes but the final price is not certain

- hedging with financial instruments can provide some protection, such as:

- exchange-traded (ET) futures, options and caps

- over-the-counter (OTC) swaps, options and caps.

- physical hedging using self-generated electricity during price peaks; for example, solar, diesel, gas fired

- hybrid retail contracts.

In the book “Power Profits – A Comprehensive 9-Step Framework for Reducing Electricity Costs and Boosting Profits” we delve deeper into each of these risk management approaches.

Another form of emerging hybrid contract is a corporate Power Purchasing Agreement (PPA) with a renewables project that offers the customer a long-term, attractive fixed electricity price during the period of solar and/or wind electricity generation, and then the remainder of the electricity is supplied at the wholesale market pool price. This residual market exposure can be managed by the DSM methods that we have covered in this article.

The term of these contracts is usually between five and ten years. Some end users balk at locking in a contract for such a long period, but in the past such long-term contracts were the norm.

I have reached agreement on a 15-year electricity supply contract that was the most competitive offer for year one of the contract and quickly became a contract that had pricing well below the retail market pricing in subsequent years. Long-term contracts tend to favour the buyer, provided you are not outwitted by the annual price escalation clause and/or take-or-pay obligations.

There are lower cost alternatives to simply accepting the best of the risk-premium laden fixed retail prices that you are offered, and the subsequent residual risks can be effectively managed through Demand Side Management, financial hedging and physical hedging.

About our Guest Author

|

|

Michael Williams has 35-years’ experience working in resource based, energy and capital-intensive industries such as iron, steel, ferroalloys, cement, quicklime, mining and waste derived biofuels. His experience in operations general management and knowledge of energy markets has led him to become one of one of Australia’s foremost practitioners in energy strategy and energy cost reduction. In 2018 his book “Power Profits – A Comprehensive 9-Step Framework for Reducing Electricity costs and Boosting Profits” was published and was widely recognised as essential reading for those interested in how the Australian electricity market works and how to reduce electricity costs.

Michael has a Masters Degree in Applied Finance and Investment, a Bachelor of Engineering in Metallurgical Engineering, a Bachelor of Applied Economics and is a Graduate of the Australian Institute of Company Directors Course. He is a Fellow of the Institute of Quarrying Australia, a Graduate member of the Australian Institute of Company Directors and has memberships of the Australian Institute of Mining & Metallurgy, FINSIA, and the Australian Institute of Energy. |

Leave a comment