One positive to come out Australia’s climate wars in the past 12 months is that the Liberal-National Coalition have acknowledged we need to completely replace coal in our power mix. However, the timing surrounding when that coal is replaced is also pivotal. This is not just because addressing climate change is urgent, but also for reasons relating to energy reliability and affordability.

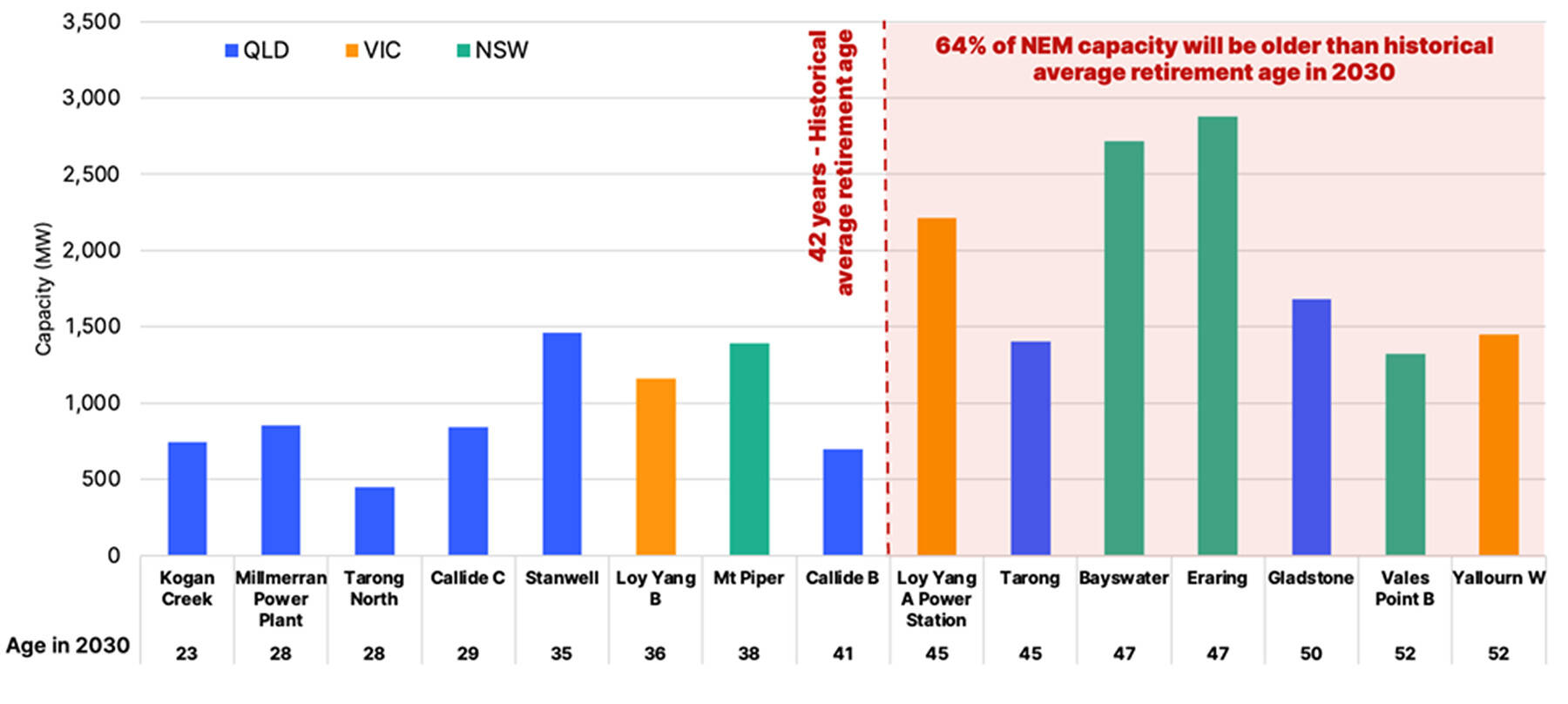

By 2030, two-thirds of the existing National Electricity Market’s coal fleet will have exceeded the average age at which past coal plants have retired – 42 years.

Age and capacity of the existing NEM coal power plants by 2030

Source: Bowyer and Edis (2025) Delaying Coal Exits – A risk we can’t afford

Coal-fired power stations, just like a car, are exposed to extreme levels of heat, pressure and movement which stress and ultimately wear out components. They can’t be expected to as reliable as they once were, and replacement will become increasingly urgent.

Yet while the Liberal-National Coalition now concede the need to replace coal, their leader Peter Dutton seems determined to choose any option other than renewable energy as the replacement. Economic modelling prepared by Frontier Economics, which Dutton says reflects their desired electricity system, implies that the renewable energy industry will collapse in a few years’ time. Last year, Australians installed around 3,200MW of rooftop solar. In addition, another 4,300MW of large-scale wind and solar farms commenced construction for a total of 7,500MW of capacity. Yet from 2030 onwards my analysis indicates that Frontier’s projections for renewable energy could be achieved with an average of around 1,000MW of renewable energy additions per year. So rather than relying on renewable energy, the Coalition will aim to replace the old coal-fired power stations with nuclear power, starting around 2037 but with most of the nuclear plant coming in the 2040’s. Dutton has also indicated increased use of gas, for example, he stated in a radio interview that,

“I want to make sure that we’ve got reliable power as well, and that’s exactly what nuclear does, but it doesn’t do it until the mid to late 2030s – and gas is the way in which we get from now to then.”

Yet such a strategy will confront two fundamental problems:

- There isn’t enough fossil gas available to fill the gap left behind from seven coal plants which will be retired before the nuclear plants come online, unless we were to confiscate the gas contracted to customers overseas.

- If coal power plants’ retirement is deferred, they are likely to encounter deteriorating reliability that will also require an increased level of gas use in power generation to cover for increased coal outages. This is likely to be of a scale that would stress domestic gas supplies, increasing gas prices and also electricity prices.

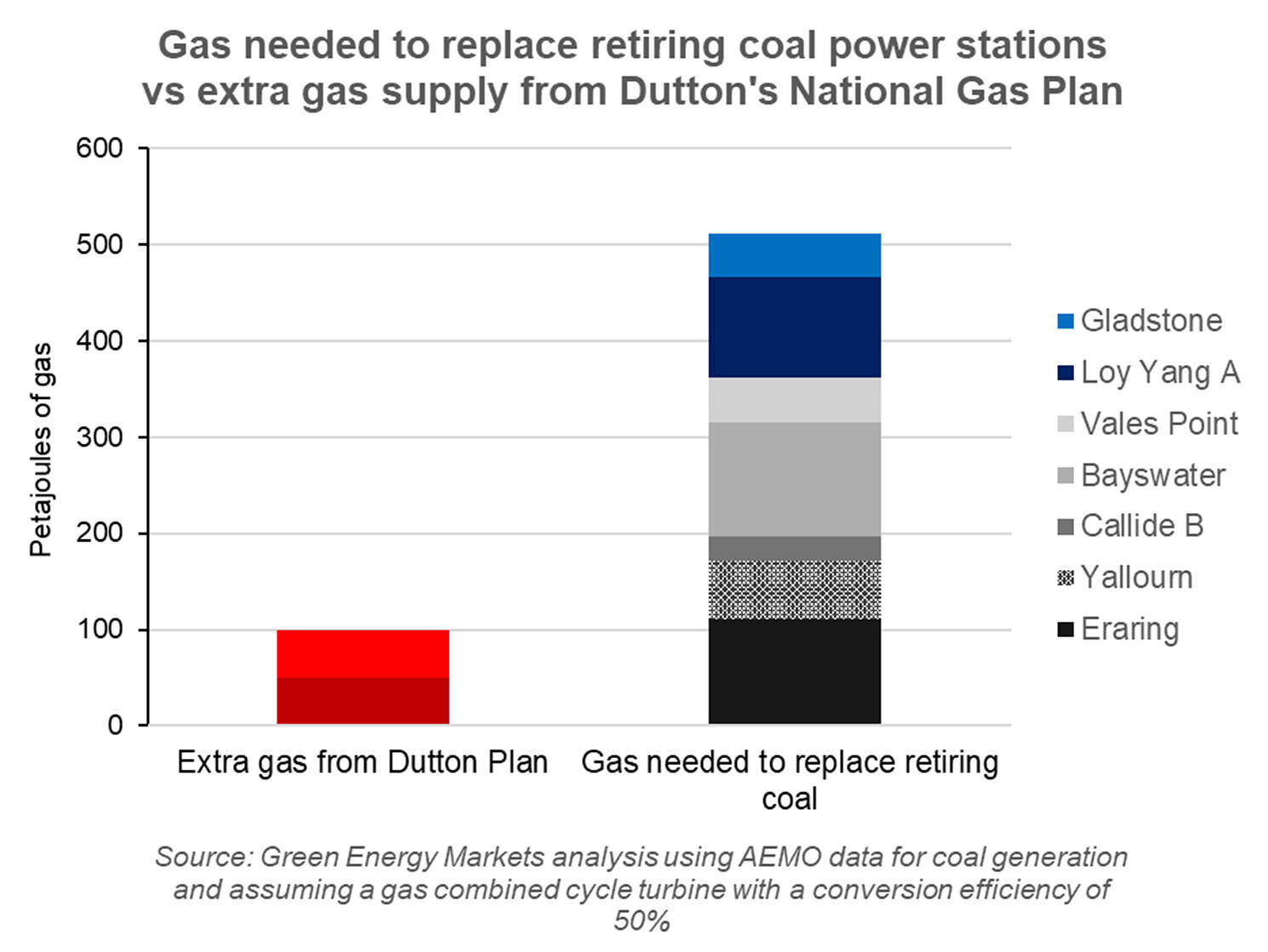

As some important context to the points above, Australia’s east coast gas market outside of Queensland is already projected to encounter gas shortages within the next few years, according to the Australian Energy Market Operator. That’s under a scenario where gas use for power generation is expected to substantially shrink from levels over the past few years. Liberal leader Peter Dutton has cited this forecast shortage as a key reason for why he will reserve 50 to 100 petajoules from Queensland gas exporters to re-direct into the domestic market. This promise of a domestic gas reserve, in conjunction with a shift to nuclear power, is central to Dutton’s claims that he will bring down energy costs. He has even claimed it will be important to bringing down grocery prices.

Yet this extra gas supply would be completely overwhelmed by increased gas demand if we rely on gas and not renewable energy to replace retiring coal power plants. The chart below shows the amount of extra gas required to replace the generation from the seven coal power plants due to retire before the Coalition claims its first conventional nuclear power plant could come online in 2037. It equates to around a doubling of the entirety of current east coast gas demand across not just power generation, but also industry and in commercial and residential buildings.

The other option, which the Liberal Party have not talked about during the election campaign, but is implied within the Frontier modelling, is to subsidise the coal generators to delay their retirement.

However, research by IEEFA analyst Johanna Bowyer and myself into the historical performance of Australian coal generators in the years leading up to their closure indicates this too would cause problems for gas supply. This research finds that as coal power stations get old and near retirement their reliability suffers – with 34% of their capacity out of service on average. To cover for this poorer reliability of coal plants, relative to the optimistic assumptions in Frontier’s modelling, an extra 52 petajoules of gas would be needed for power generation in 2034 rising to 93 petajoules by 2040. While not as catastrophic for gas consumers as trying to replace the coal entirely with gas, it heavily depends on nuclear plants being built on a rapid schedule that is incredibly unlikely to be achieved.

This suggests that even in a scenario where the Coalition was to prop-up old coal power stations, their gas reserve will be largely gobbled up by extra demand from gas generators having to fill-in for regular coal outages. This would mean the gas reserve would probably deliver little to no reduction in gas prices.

But the other issue is what this might mean for electricity prices. The Australian Energy Regulator in its 2023 State of the Energy Market Report observed:

“Coal generators break down more frequently as they age – the NEM’s aging fleet of coal generators is particularly prone to outage as stations near the end of their lives. Outages of coal plant, particularly unplanned outages, were a significant contributing factor to the record high prices of the April to June quarter 2022, which saw the spot market suspended for the first time in the NEM’s history. In the April to June quarter 2022, coal outages in the NEM reached nearly 8 GW compared with historical averages of 3 to 4 GW. This saw a large portion of electricity demand shifted to more expensive gas generators, which were not prepared or appropriately contracted for the additional workload.”

More recently, in quarter four of 2024, AEMO found that:

“Lower coal availability also contributed to several high-priced events in New South Wales and Queensland on peak demand days, driving up average prices in those regions”

The issue here is that coal generator breakdowns can come suddenly, giving other energy suppliers little to no time to prepare and respond so we end up with prices spiking dramatically upwards. If we assume they’ll be as reliable as they used to be and subsequently decide we don’t need additional new supply from renewable energy, then we’ll get ourselves into trouble. Sure, wind and solar also vary significantly but the issue is one of forecasting and planning for this variability so it can be managed through energy storage and transmission, not assuming it away.

Unfortunately, gas (or at least gas uncontracted to overseas customers) is not plentiful and it certainly isn’t cheap. So it isn’t viable to play the role of a stop gap to replace aging coal that can tide us over until nuclear power plants come online in possibly 15, but more likely 20+ years’ time (putting aside the fact nuclear power is incredibly expensive). Yes gas will be useful into the future, but it is something we can only afford to use sparingly.

About our Guest Author

|

Tristan Edis is the Director of Analysis and Advisory at Green Energy Markets. Green Energy Markets provides analysis and advice to assist clients make better informed investment, trading and policy decisions in energy and carbon abatement markets.

You can find Tristan on LinkedIn here. |

Good article – although I question some of the conclusions drawn around the role gas CAN play or rather the assumptions used to draw these conclusions. What would be interesting to know to qualify some of the conclusions drawn in this article are the following:

– How much additional gas could be brought into the east coast gas system by increasing gas exploration? Given Victoria’s moratorium on gas supply – one would assume a decent amount without considering the additional gas production potential of QLD and NSW that could be acheived from further exploration. How far would this additional gas, combined with a gas reservation policy (which in my view is desperately needed and stupidly never implemented) go to meeting the gap?

– Taking into account the above, how much additional renewable energy would be needed to then fill the gap over the next 15-20 years until nuclear is available? The statement above that the Coalistion’s plan assumes that renewable energy industry will collapse in “a few years” seems overdone – what is this based on? If it’s simple the frontier economics report, well we know that is just a model and is probably wrong just like the ISP is probably wrong.

– My gut feel here, it is critical to continue to accelerate renewable energy development, gas development and start nuclear development to meet our future energy needs – the politicisation of energy is preventing thisand I think its risky to draw a conclusion that gas supply won’t be enough and nuclear will never be built. This is self fulfilling rhetoric that doesn’t focus on solutions to the problem, and adds to the polarisation of the debate. This article, without saying it seems to imply that the only solution is full scale renewable energy deployment – which while I agree this is part of the solution, discounting other potential parts of the solution (a.k.a gas and nuclear) is risky rhetoric, particularly given the massive uncertainties we face over the next 50 years in not just energy markets but international markets and politics.

But as the research also says, “operators often make strategic decisions to scale back asset management and capital investment in ageing coal plants, opting against major upgrades due to their limited remaining operational life and the shortened window to capture a payback on upgrade investments”.

If the planned closure is pushed back, won’t that likewise delay the onset of this ramp-down in maintenance, thus deterioration will be similarly delayed?