In earlier articles for WattClarity, I examined both how retailers normally hedge and generators often hedge by explaining the usual contracting approach.

This is well known to those involved in energy trading, but I’d seen little description of how it works as a portfolio in any publicly available material, so I thought I’d expand on the concept to better inform readers of just how this usually works.

In each of these prior articles I examined the hedging that would take place, and the following assumptions would normally be true:

- Retailers endeavour to hedge at least by the time the customer load has been contracted i.e. the fixed price to the customer is predicated upon a known contract price and a valuation of risk and other costs, so it is imperative to “lock in” a known hedging contract as soon as possible

- Retailers normally use swap contracts (or their futures equivalent) to hedge customers and may use cap contracts at their discretion

- Most Generators will have usually filled their hedges close to rated capacity so that they have high levels of contracting at the point in time when their contracts are live i.e. for the 2025 contract period, most of the contracts to hedge the generator would be in place by late 2024.

- Generators usually sell swap contracts (or their futures equivalent) for baseload or intermediate plant, whilst peaking plant usually sell caps.

Whilst these four conditions are usually true, it does not reveal the true complexity of an electricity contract portfolio for a retailer and/or generator in the NEM. More specifically, it is important to understand that individual contract portfolios are usually matched against specific customers and/or generators. These businesses will also employ other portfolios often known as “trading” portfolios which are used for the purposes of enabling the use of appropriate contracts for the “hedging portfolios”, to warehouse risk and take a financial position with the aim of turning a profit.

Firstly, it is worth examining a subtle but important difference between contracts that are bilateral between two parties, and futures which are settled by an exchange.

OTC vs Futures

When the National Electricity Market started in 1998, all contracts were “Over-the-Counter” (OTC) which meant most derivatives were bilaterally negotiated between parties, except vesting contracts which were organised by government between state-owned generators and retailers. OTC contracts settle each week as per the NEM settlement schedule, four weeks in arrears. i.e. What this means is that the settlement does not occur until all the energy spot market periods have occurred and have been settled. As an example, a 2024 calendar year contract will not be fully settled until late January 2025 because it aligns with the spot market settlement, which is 4 weeks in arrears. Normally, counterparties first sign an ISDA (International Swaps and Derivatives Association) master agreement which sets out the main terms of all potential trades and when required specifics such as price, contract type, term and region are agreed for each individual trade.

Futures by contrast, settle through the Australian Securities Exchange each business day both before the contract period commences and when it is live. What makes futures different from OTC contracts are the following:

- Futures are margined, i.e. buyers and sellers contribute initial financial margins when opening a trade, and when the value of contracts change

- Contract types are rigidly defined and cannot be modified

- Futures go through an exchange, so aside from some exceptions, such as pre negotiated trades, trades are anonymous

- If the same contract is bought and sold, the position nets to zero and the profit or loss is realised as funds in a trading account, with no further financial exposure

- They do not require a credit rating or assessment of counterparties that you implicitly trade with but a futures broker will need to be satisfied with your creditworthiness

- Futures contracts can be entered into a number of years before the contract starts or even after the commencement date of the contract

Use of portfolios

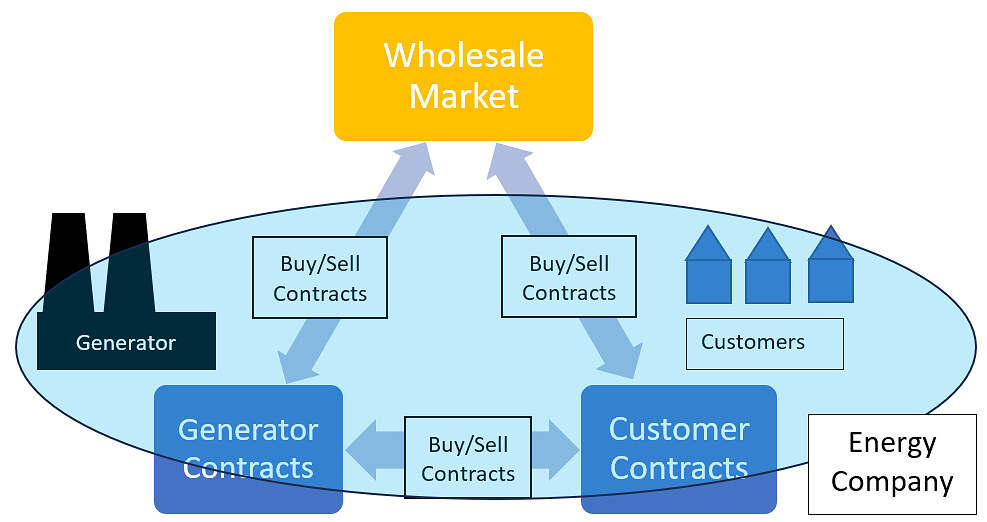

Most businesses will utilise a portfolio of contracts against each aggregation of load or generation in a given NEM region. The levels of aggregation can vary but our first example we can consider a business with a single generator and a few customers as illustrated in figure 1. (Noting that counterparties only trade with a single business entity, not necessarily each portfolio)

Figure 1: Simple example of a business with generation and customers in a single region

What is important to understand is that each of the generator and customer contracts portfolios are able to buy and sell contacts to each other and the broader wholesale market even if the external market trades with a single entity. This shows the importance of trading as this enables the business to:

- Buy contracts when there is not enough generation to hedge the customer portfolio

- Sell contracts when there is too much generation to match against customer portfolio

- Trade with the external market because the generation portfolio does not perfectly match the customer demand

- Buy/sell contracts when customer forecasts change or there are changes in planned future generator availability

In this fairly simple example, we could imagine a scenario where both the generator and the customer portfolios are “fully hedged” i.e. they are contracted at a level that minimises exposure to the spot market (as explored in earlier articles). This could be done at a time well in advance of the contract period. This would mean that the generator is measured against its ability to perform to its contracts and the profitability of the customer portfolio’s will be measured against whether or not there was sufficient margin in the customer price to cover the underlying contract prices as well as the cost of market exposure when the load was above or below the hedges. This arrangement has merit in that each of the business units are effectively measured against what they have control over i.e. has the retail business appropriately added sufficient margin retail margin to be both competitive and profitable and have the people responsible for the generator maintained good availability of the generator. It generally means that the opportunity cost of entering into contracts at the best time is the responsibility of the “front office” or the wholesale contracts trading desk.

One of the next concepts to consider is “mark-to-market” as it is relevant to what may happen to the contract values between when a contract is entered into and when it closes at contract expiry.

Mark-to-market

“Mark-to-market” is a methodology of reporting profit and loss by valuing open contract positions against the fair market value of those contracts. It is not without irony, that around the turn of the century that Enron was a strong advocate for the use of mark to market so its business could identify profits based upon the change in market value of a number of OTC contracts. This meant that the business and its employees could be rewarded (or not) on an as a yet to be realised profit (or loss) in market valuation and bonuses respectively. The challenge with this methodology is where markets are thinly traded or illiquid and/or dominated by a single entity which means that prices are difficult to determine and can be artificially manipulated to mask losses or inflate profits. In the Australian context, in 2003/4 two rogue foreign exchange traders covered up a loss of $360m at NAB through a combination of entering false trades and because they employed a mark to market methodology where the market prices for a number of derivatives were measured by the middle office using priced supplied by broking firm, ICAP, where in turn, its “independent” middle office market prices were created by data sent by NAB. Used legitimately, it is a meaningful measure of the financial performance and the use of futures for these trades, eliminates much of the opportunity for fraud as an exchange has much better transparency, regulation and values that seem too high or low present a trading opportunity rather than just an over/undervalued number on a spreadsheet.

Trading for Profit

“Trading for Profit” is the trading of contracts primarily for the purpose of risking capital for the goal of earning an above average return. Profits are normally realised in two ways:

- Positive movement in the value of a derivative such that the purchase and sale realises a profit before the contract is live.

- Holding a contract for the active period of the derivative earns a profit when exposed to spot prices.

Often, a portfolio of trades is used to take advantage of both these ways to make a profit in aggregate.

As an example of #1, could be to purchase a 10MW swap for the next calendar year at $90/MWh in January this year and then sell it for $100/MWh in November. The profit is then 8760 hours X ($100-$90)/MWh X 10MW = $876,000. Noting that in a futures trade, that the profit is realised the day the position is closed, whilst a swap contract settled weekly, 4 weeks in arrears pays (7*24 hours * $10/MWh * 10MW) $16,800 each whole week, from late January of the contract year to late January, the year after. The fact that futures are closed out at the time of the trade, with no future exposure means that additional trading positions can be entered into to make additional profits. It’s plausible that someone could trade a future and a swap to make a profit, but the cashflows are more complex and variable from week to week.

In the case of #2, it may be believed that derivative prices are too high and not reflective of what the spot market, or conversely too low, so a business may sell or buy respectively, a swap contract with the expectation of making a profit. The profit realised on a flat swap is simply the difference between the contract price and the average spot price, multiplied by the contract volume (MW X hours). This type of “naked” trade is often perceived as more risky because of the high variability of spot price outcomes and hence the possibility of more significant losses if the spot market prices are not as expected. Both futures and OTC trades require contracts to be held to expiry, meaning longer periods of time to realise profits (or losses).

These cases simply touch on basic examples, but a trading business will likely have a portfolio of trades with the expectation that most trades in the long run make sufficient profit to cover overheads and make a reasonable profit.

The need for a “Trading” Business

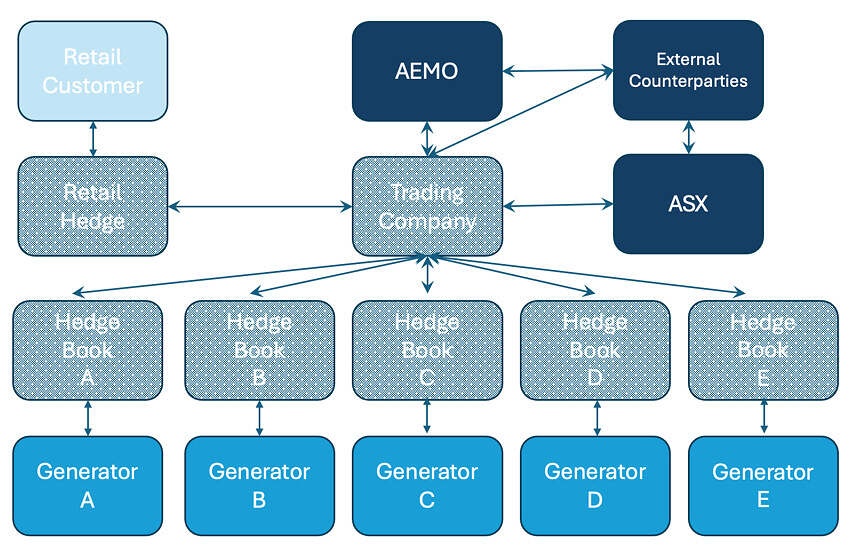

Most NEM participants that own more than one generator or have customers will have a trading business that manages the derivative trading with the ASX and other counterparties, as well as the electricity pool settlements each week.

It’s first worth noting that AEMO recognises key roles for generator registration being:

- Owner: the asset owner

- Operator: the business responsible for the O&M and day to day plant operations

- Controller: the entity that interacts with AEMO for market operations, bidding and settlements

- Intermediary: A business that takes on novated responsibilities, often controller on behalf of third parties

This means it can be beneficial for a trading business to take on the intermediary role on behalf of individual generators. This happens for the following reasons:

- Economies of scale for generator control centres

- Business can take a portfolio view, covering customers, generators and energy storage

- AEMO allows netting off of customer pool purchases against generator revenues meaning smaller bank guarantees and lower overheads

- A larger single corporate entity will likely have a better credit rating than individual generators, making it simpler to trade OTC and futures

- Adding a generator to a trading portfolio should not require additional administration to enter into additional trades

- 3rd party asset owner such as a renewable generator does not have market facing function

In practice, if you examine AEMO’s list of generators, you can see that some participants have portfolios of generators, such as AGL Hydro Partnership, or AGL Loy Yang Marketing, each of which have a portfolio of generators in addition to their main registered asset.

Expanding on the concept in figure 1, we can create a hypothetical example in figure 2, showing a potential structure, where the trading company is the entity which has cashflows with AEMO as the market operator, the ASX and other trading counterparties. It essentially manages the trading book, containing trades with third parties and internal trades with each portfolio. Whilst many trades are simply a pass through (i.e. buying an external contract and writing the mirror contract internally to the relevant hedge book, there may also be instances where this is not the case, which means that the trading company is effectively taking a speculative position.

Moreover, we’d expect tight limits on the hedging portfolios to best match contracts to the anticipated generation or load and any speculation about markets prices or spot price outcomes are within the trading portfolio. The key enablers of the portfolio approach are:

- Profit and loss of generator(s) can be measured against its ability to deliver against its contracted position.

- Profit and loss of retail customers can be measured against hedges in place and appropriate retail margins to make a sufficient return.

- The Trading portfolio is where speculative trades, managing the timing of trades or recognising when it is best to buy, or sell are made. Profit (or loss) is transparent in making appropriate decisions about value, market trends and spot price outcomes.

Figure 2: Example of a Trading company to support a portfolio of generation and customer load

To elaborate a little more on some potential trading decisions the business may consider the following:

- Purchase (sell) contracts in advance in anticipation of market prices falling (rising) to either sell back into (buy from) the market at a profit or to the customer (generator) portfolio for more competitive prices.

- If transacting a hedge in a region is challenging, transact in an adjacent region with the market, write an internal deal in the desired region, creating an interregional hedge, with the trading portfolio taking a speculative position on the difference in prices.

- Accept some basis risk by selling a swap and buying a cap contract, with the view that the swap payout is more than offset by the cap payout net of cap premia paid.

- Purchase or sell options for the delivery of swaps, caps or futures.

- Purchase a PPA from a renewable project and sell a firm financial derivative such as a swap against, pricing the PPA at an appropriate discount to a firm contract.

These examples are not exhaustive but represent some of the potential trades that may be entered into in a trading portfolio.

Conclusion

Many NEM participants have a portfolio of generation and customer loads to manage. It is usually more effective to have a single entity to trade externally and then write internal deals with each asset or customer group, such that effective trades that align with the risk management policy are made for each hedge book. Contracting risks are made by a trading portfolio, which will have some elements of speculation allowed, depending upon the risk appetite of the overall business. Each assets’ performance is then measured against the contracts written against it, whilst the speculative or “risky” part of trading is measured against a trading portfolio where an experienced trading team is expected to make longer-term higher returns which are reflective of the market risk that they take.

About our Guest Author

|

Warwick Forster is an experienced energy professional with 20 years of experience covering energy trading, risk management, market operations, retailing, pricing, renewable project development and energy storage. He is now an independent energy markets consultant operating through the business, Apogee Energy.

You find Warwick on LinkedIn, and Twitter. |

Brilliant article, thank you Warwick.

Thanks for this Warwick, I wonder what happens to to liquidity in the futures/swaps market as coal exits, surely it is difficult for renewable energy owners to contract with retailers because they in most cases already have PPAs, and besides cannot be sure enough of volume and price realised to take that side of the trade.