This article has been prepared as one part of a more general summary of the Opportunities & Threats to energy users in Australia’s National Electricity Market (NEM).

Note that my focus is primarily towards large Commercial & Industrial (C&I) energy users – such as those who would be eligible for membership of the Energy User’s Association of Australia (EUAA) – however the concerns would be generally valid for all types of energy user, including small businesses (such as ours) and “mums and dads at home”.

I’ve split this analysis into a (growing) number of parts to enhance readability (i.e. so you can focus on what you’re interested in). It’s also helping me to put this analysis together progressively – in between my normal job!

The general post is linked here, for your reference (you’ll see in that article the bits in red are placeholders for further commentary, which will be added as time permits).

Energy users have a significant concern about wholesale spot prices rising in future years.

These concerns have been aired by the majority of energy users who have presented at recent EUAA seminars, and have been supported by most of the other presenters on these days.

A. Historical Trend in Prices

I’ve recently posted some analysis of the way in which prices have trended in the 17 years since the competitive electricity market was first introduced in Australia (beginning in Victoria in 1994 and progressing to the National Electricity Market in December 1998).

As noted in that post, a person could just as easily see that current prices are lower than they have been in the past, or higher than they have been in the past – it all depends on the historical period to which they are referenced.

It’s also apparent that current prices are not outside the range over which prices have trended in the past.

With this in mind, I’d like to discuss a number of the factors that need to be considered in determining where prices might head in future.

B. Trend for the Future

We’re not a consulting company that produces our own forecasts of the future of the market.

Rather (in the same approach we adopt in general) we take the approach of collating and communicating as many relevant factors as possible, to enable our clients & readers to make their own judgement of what the future might bring.

I have tried to include a long list of drivers on both sides of the equation i.e.

(a) some driving prices higher, and

(b) others supporting softer prices.In some cases commentary has been provided, whilst in other cases (where discussion was scant at EUAA events) less commentary has been included.

1) Balance between supply and demand

The greatest driver supporting a trend in prices (higher or lower) is the trend in the balance between supply and demand.

It is for this reason, for instance, that we include a real-time view of the Instantaneous Reserve Plant Margin within NEM-Watch.

In considering this trend, it is important to keep in mind the fact that both sides of the equation are not equal.

What I mean by this is that it’s commonly accepted that demand (because it is distributed, and the result of millions of individual purchasing decisions) will continue to grow forever into the future, whereas new supply sources for electricity (because they are lumpy, and subject to only a relatively small number of investment decisions) are seen as discrete events – hence not guaranteed.

Because the supply and demand sides are not seen consistently, it can be relatively easy to slip into a paradigm in which we look at a relentlessly growing demand curve and a (seemingly) fixed supply curve and draw the conclusion that prices will rise in the future. This is an over-simplification that can be dangerously misleading.

For instance, I have highlighted in previous posts that:

(a) The addition of new generation supplies in the NEM over the past 10 years has almost kept pace with growth in demand, on an annual average basis.

(b) The distribution of surplus generation across the NEM at the time of peak winter demand has been largely the same over the 8 year period from winter 2002.

(c) That’s not meant to imply that the market is perfect, however, as it was certainly surprised in summer 2008-09 by higher-than expected peak demand, in the same way that the market was also surprised in winter 2007 by a early arrival of peak demand.

With respect to both supply and demand, the following additional comments can be made:

1a) Demand growth

It was noted by several speakers that demand growth had slowed in more recent times.

Some speakers had attributed this slowing of demand growth to the GFC – however (in July 2009) I noted how the slowing of average demand growth was seen to pre-date the GFC, and might be due to factors such as energy efficiency measures.

1b) Generation Capacity

Because of the lag time between investment decisions and commercial operation for new stations, this has meant that there is currently a higher volume of surplus capacity than would have been the case otherwise.

Several speakers have noted that the increased amount of renewable generation that will need to be built to meet the increased renewable energy target will represent an increase in the installed capacity base – which may (depending on when this plant runs) act to keep a lid on prices in future.

Other speakers have noted that the volume of wind capacity in already starting to have an impact on prices in the NEM – and is one of the reasons for the lower prices this year.

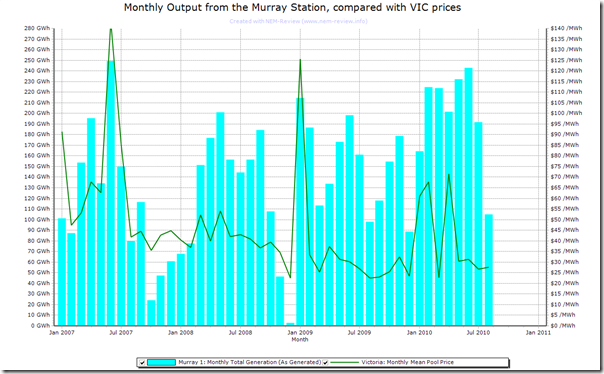

Still other speakers have noted how the increased output from hydro plant in recent times has had a depressing impact on spot prices – this is illustrated in this chart (from NEM-Review) for the Murray hydro plant in VIC:

2) Locational Issues

As noted in numerous other posts (such as this one), the incidence of inter-regional transmission constraints in the NEM is one of the biggest drivers of price volatility, which represents a significant percentage of the annual average wholesale cost of electricity.

However, in more recent EUAA events, transmission congestion has not rated as much of a mention.

The creation of a single national transmission planner within AEMO is supposed to deliver a more streamlined process for the upgrading of national transmission flow paths – however it seems to me that any improvements are still very conditional on the form of the Regulatory Test, and the extent to which “customer benefits” (in addition to “market benefits”) can be incorporated into the NPV calculation.

3) Input Costs

Coupled with the considerations (above) of the supply-demand balance are also considerations of where input costs are trending, in relation to significant attributes of the electricity supply industry.

Even if the supply/demand balance were to remain steady in future, any increase in costs would flow through to an increase in electricity prices, whereas any decrease in costs will flow through to decreasing electricity prices.

Hence, in this section I have outlined some thoughts on factors influencing input costs:

3a) New Entrant Costs

Economic theory holds that the wholesale cost of energy should trend towards new entrant prices.

I have previously posted about some comments made by Paul Simshauser at the EUAA Annual Conference 2009 – which were in relation to new entrant prices, amongst other things.

About 9 months after Paul’s presentation, Rohan Zauner (of SKM) spoke at the EPMU on 16th June 2010 (as he has every year over the past decade) to update delegates on how new entrant costs are trending for a couple of different possibilities for new coal or gas generation plant configurations in the NEM.

From my perspective, Rohan’s analysis and presentation has improved each year, and it is one that I look forward to at each successive EPMU. Part of this anticipation has stemmed from the fact that, perhaps unlike the early years of the last decade when new entrant costs were relatively flat and predictable, there is now greater variability in these costs, from one year to the next (and also in terms of comparing one asset type with another).

In his 2010 presentation, Rohan highlighted how two separate factors were now combining to influence new entrant prices:

i. Cost of Equipment

With the ongoing boom in China & India forcing up prices for underlying commodities, Rohan highlighted how the cost of major inputs into power station construction (e.g. steel) were still above the levels experienced across most of the past decade.

It was noticeable in the chart provided that reference prices for concrete had not suffered from the same escalation as had been the case for various steel indicies.

ii. Cost of Capital

Rohan also included a trend of Australian bond spreads that highlighted how the spread for BBB Corporates above government yields was still in excess of 200 basis points – though certainly down from the peak of almost 6% at the depths of the GFC.

As Paul Simshauser had noted 9 months earlier this risk premium was being factored into the cost of capital applied to potential new power station developments, and was one reason why new project development has been more difficult in the past 18 months or so.

iii. Foreign Exchange Rate

In his presentation, Rohan also touched on foreign exchange rates – with both the US$ and with the € – with the latter assuming increased importance in recent times due to the increasing amount of plant being sourced from European suppliers.

It was shown that cycles in exchange rates tend to be shorter than a 10-year time horizon, hence the effect they will have on new entrant prices tends to be more transient than those based on major commodity cycles.

Rohan pointed out that his calculated long-run marginal cost (LRMC) for combined cycle plant types was marginally higher in 2010 than in the previous years, whilst calculated LRMC for coal-fired plant showed a reduction from the levels reported in 2009. Comparisons with his presentations made in years prior to 2009 is not so easy because of the fact that greenhouse implications have been incorporated in his input assumptions in 2009 and 2010, but not in prior years.

For those who want more information, they can request a copy of the paper by Rohan by using this form on the SKM website (you might want to haggle with Rohan, as this form references his report from 2007).

3b) Fuel Costs

I have previously posted about how some aspects of fuel supply are upward drivers on electricity prices.

However, it is important to note that other speakers made the point that the development of one (or more) LNG projects on the east coast would have a temporary effect of providing surplus supplies of coal-seam gas to the NEM at low prices – and delivered under “take or pay” contract structures. This will have the effect of driving spot prices lower as GT generators bid to run at any price.

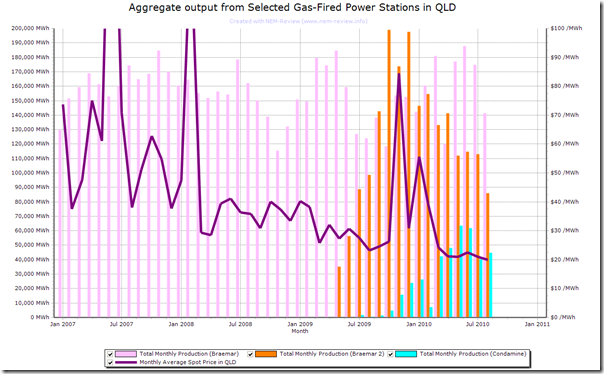

These arrangements were cited as one of the factors driving current spot prices lower – with stations such as Braemar, Condamine and Daandine (in QLD) noted by some as stations operating under these arrangements.

The following chart, from NEM-Review 6, shows monthly production volumes from Braemar and Condamine in conjunction with QLD spot prices (Daandine can’t be shown as it is a non-scheduled plant for which data is currently not published):

In particular, Mitch Anderson (of ERM) spoke at the EPMU 2010 about the fact that there might be a number of years where ramp gas will continue to be available – and hence prices lower as a result.

3c) Increased Equipment Costs, for O&M

I have discussed (above) that materials costs in recent years have been seen to be higher than the long-run average of the 1990’s

It was not discussed, but it seems logical that these increases in cost for plant and equipment are also being felt by operational stations.

3d) Increased Labour Costs

I can’t recall it being mentioned explicitly by any speaker – though I assume that it must be an issue (to some degree) that the power stations are often located in regions that compete against the mining industry for skilled labour.

Labour cost represent a relatively small proportion of a station’s total cost of operations, but any increase in labour costs would still have some impact on electricity prices.

3e) Resources Super-Profits Tax

At the EUAA EPMU (on 16th June 2010) this represented a looming issue that might have resulted in higher fuel costs to power stations operating in the NEM.

However it may be that this situation has since been resolved – it’s really a case of “watch this space” in terms of the ongoing uncertainties following the Federal election.

4) Market Dynamics

Several other points have been made about various aspects of the way the market operates, and how these are seen to have an impact on the price outcomes in the NEM.

4a) Recent Increase in the Market Price Cap

Most obvious is the recent increase in the price cap. From 1st July 2010:

i. the “Market Price Cap” (MPC, formerly known as VOLL) was increased from $10,000/MWh to $12,500/MWh, and

ii. the Cumulative Price Threshold was also increased (from $150,000 to $187,500)

This increase was made following this decision by the AEMC in the interests of ensuring that the NEM would continue delivering sufficient supplies of new capacity into the future.

Because the MPC tends to bound the upper prices offered by generators for the last component of their supplies, this increase in MPC is significant (indeed, it could be argued that it was designed to be so).

In practical terms, a single half-hour at the MPC now adds an additional $0.14/MWh to the annual average cost of energy in a region across a whole year – hence it will have a significant difference to the average cost of wholesale electricity (all else being equal).

4b) Reduced Liquidity

It has been noted by various speakers that the level of liquidity is lower than desired.

Whilst this has obvious implications for energy users (with retailers unable to hedge their loads, and hence reluctant to offer long-term contracts) it also has impacts for the wholesale electricity prices.

My understanding is that this reduced liquidity is occurring for a number of reasons, including:

i. Uncertainty surrounding carbon pricing

This has been the topic of conversation for a number of years now, and does not look like going away.

The comment was made by several people at the EPMU was that the uncertainty now does not only extend to what the start date of an ETS would be, and the reductions trajectory (and hence the price) – now the uncertainty extends to whether it will be a market based mechanism or just a carbon tax.

Because of this ongoing uncertainty, liquidity is almost non-existent more than a year or two into the future.

ii. Uncertainty surrounding privatisation in NSW

There have been numerous references made to the ongoing uncertainties surrounding the drawn-out privatisation process in NSW – including the fact that ongoing uncertainty over carbon cascades into ongoing uncertainty in terms of the privatisation process.

It has been noted that the uncertainties have led to the unavailability of hedge cover in the NSW region, and the inactivity of the main government-owned retailers in winning new business elsewhere, and hence seeking hedge cover for their new business.

iii. The advent of the financial traders

At the EUAA EPMU on 16th June 2010, Ken Thompson (of LYMMCO) noted that the entry of financial intermediaries into the NEM (investment banks, hedge funds and other traders) had resulted in generators being more exposed than they would like to spot prices.

The increased exposure will increase a generator’s risk exposure, and hence their desire to influence the spot price, where possible – greater higher volatility, and higher average prices as a result.

4c) Generator Market Power

This has been a concern voiced by EUAA, and other energy users, at various points in the past – however it has not voiced as much in recent events.

5) Ongoing uncertainty about Carbon

This is worth a separate, special mention.

Despite the demise of the proposed Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme (CPRS) the general consensus seems to be (amongst energy users and others at EUAA events) that a carbon price will be implemented eventually, in some form.

Hence, carbon policy is having two effects:

5a) Current

Given the current uncertainty, it is commonly understood that participants are favouring the development of projects with lower capital costs (but conversely higher operating costs per MWh produced). As such, this is putting an upward pressure on prices currently, and will continue doing so until the uncertainty is resolved.

5b) Potential Future

With the obvious objective of any carbon policy (however it is finally implemented) being to accelerate the closure of the higher-carbon older coal plants, there will almost certainly be implications for electricity prices in the longer term as the plant mix is changed, resulting in:

i. Higher costs as a result of a shift to gas as a fuel (which has higher short-run marginal cost than coal does now); and

ii. Accelerated depreciation of the existing installed base for coal fired plant around the NEM:

It may be that (if proposals such as the recently mooted purchased closure of Hazelwood are to proceed) some of this cost of closure is met out of taxation revenue, and is not passed through in electricity costs – but this is considered unlikely.

iii. Higher funding costs because of increased capital requirements for the industry to fund the accelerated build – as implied by Paul Simshauser at his presentation at the EUAA Annual Conference in 2009.

6) Anything else?

Please accept my apologies for any of the following:

i. Any drivers I have omitted

ii. Any drivers I have not described correctly, or clearly.

iii. Any comments I have mis-attributed.If you can let me know of any mistakes I have made, please (07 3368 4064) I will correct these errors above – or elsewhere in the post.

Leave a comment